Wayne Fournier was sitting in a town meeting when he had his big idea.

As the mayor of Tenino, Washington (population: 1,884), he’d watched the pandemic rake local businesses. Residents couldn’t afford groceries. Long lines snaked outside the local food bank. For more than a month, the downtown area looked almost abandoned.

To bring back the economy, Fournier needed to act. “We were talking about grants for business, microloans, trying to team up with a bunch of different banks,” he tells The Hustle. “The big concern was, ‘How do we directly help families and individuals?’”

And then it hit him: “Why not start our own currency?”

The plan came together fast. Fournier decided that Tenino would set aside $10k to give out to low-income residents hurt by the pandemic. But instead of using federal dollars, he’d print the money on thin sheets of wood designed exclusively for use in Tenino. His mint? A 130-year-old newspaper printer from a local museum.

Fournier’s central idea is pulled straight from Tenino’s own history. During the Great Depression, the city printed sets of wooden dollars using that exact same 1890 newspaper printer. Within a year, the wooden currency had helped bring the economy back from the dead.

By reinstating the old currency now, Fournier has accidentally become part of a much bigger movement. With businesses worried about keeping the lights on and people scrambling to find spending money, communities have struggled to keep their local economies afloat.

So they’ve revived an old strategy: When in doubt, print your own money.

Today, these so-called “local currencies” might help small communities recover from the economic fallout of COVID-19.

Tenino’s big bet

Fournier isn’t your cookie-cutter politician. A firefighter since the age of 18, he first gained local notoriety for a series of Banksy-style guerilla art projects that took a jab at local leaders.

Soon after he revealed himself, he won a spot on the city council; four years later, in 2016, he became Tenino’s mayor.

Wayne Fournier, mayor of Tenino, Washington (courtesy of Wayne Fournier)

To hear Fournier tell it, until COVID-19, the community had been on the upswing.

Fournier was working on plans to create 150+ new agricultural jobs. But Tenino’s businesses — which are locally owned and run on small margins — weren’t built to weather a lockdown.

“There’s a lot of them that have already said they’re not going to reopen,” says Fournier, “[and] the ones that have been hanging on are going to need a boost.”

The city is also poorer than the rest of Washington state. “We have a higher rate of kids in our school district that receive free and reduced lunch,” says Fournier. “There’s a higher rate of folks who are in poverty.”

Fournier’s local currency program works like this: Residents below the poverty line can apply to receive money from the $10k fund that Tenino has set aside. Fournier says they also have to prove that the pandemic has impacted them, but “we’re pretty open to what that means.”

Once they’re approved, they can pick up their stipends, printed in wooden notes worth $25 each. The city is capping the amount each resident can accrue at 12 wooden notes — or $300 — per month. According to Fournier, each note features a Latin inscription that means, basically, ‘We’ve got this handled.’

The spending comes with a few restrictions: Residents can’t use the money to buy cigarettes, lottery tickets, or alcohol. The currency is designed for the essentials, including food, gas, and daycare. Almost every business in town accepts the wooden notes, and twice a month, they can submit redemption requests to the city to turn the notes into cash.

Tenino’s wooden currency (courtesy of Wayne Fournier)

But why print the money on wood? Why not just give residents $300 worth of federal dollars?

The answer is simple: By creating its own local currency, Tenino keeps the money in the community. As Fournier puts it, “Amazon will not be accepting wooden dollars.”

“The money stays in the city. It doesn’t go out to Walmart and Costco and all those places,” says Joyce Worrell, who has run the antique shop Iron Works Boutiques for the past decade. Worrell sells clothes, jewelry, and — in an outdoor garden that adjoins her shop — an assortment of furniture. These days, she’s added masks and disinfectants.

Closing down business these last few months, Worrell says, was “a catastrophe for a lot of us.” But she has rallied around the wooden currency as a way to revitalize the local economy — after all, it worked for the city once before. The currency hasn’t woven its way into her store yet, but she’s expecting it soon.

“A lot of the people in our city work for places that hire low-wage help, part-time help, so they’ve been out of work this whole time,” Worrell says. “This shows that we’re doing something as a community to really step in and help.”

The origins of the ‘wood standard’

In Tenino, wooden currency goes way back.

Originally home to the Nisqually tribe, outside settlers first arrived in Tenino in 1851, when a gold rusher from Maine established a farm alongside the nearby Scatter Creek. In 1872, the Northern Pacific Railroad added a new station in Tenino, and for a time, the city was the northernmost stop on the West Coast.

By the mid-1900s, the world knew Tenino for three things: its lumber business, its quarries, and its wooden currency.

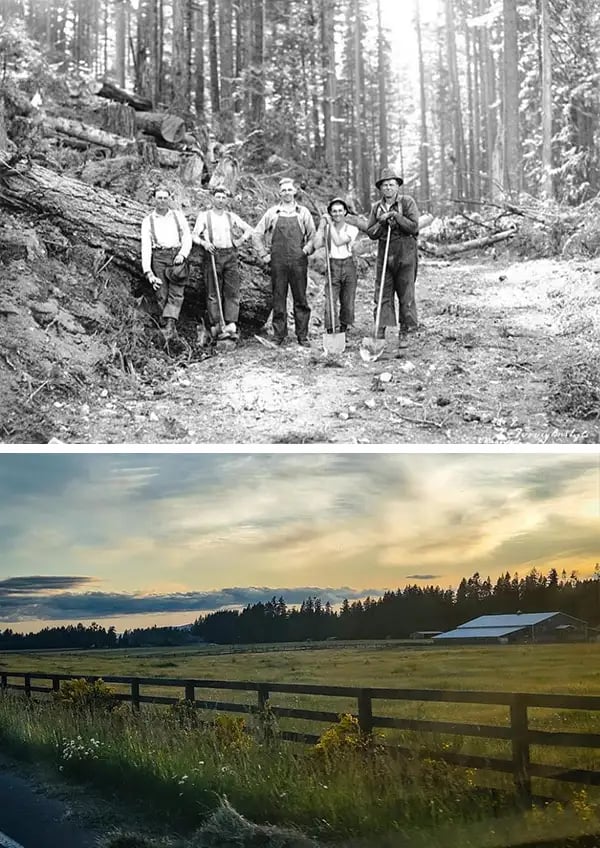

Top: A logging construction crew in the woods around Tenino, Washington (Photo via University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections): Bottom: Open land around Tenino today (courtesy of Wayne Fournier)

The legend of the wooden currency started in December 1931, when Tenino’s only bank closed shop. The Great Depression was ripping through the country and countless townspeople lost their savings. Most had to stretch the little money they had to pay for groceries, rent, and other essentials.

A local newspaper publisher named Don Major pitched a solution: With the bank gone, Tenino could invent its own currency. The officials agreed, and Major printed a series of notes — 25 cents, $1, $5, $10 — on rolled Sitka spruce. He and two local doctors agreed to back all of the currency themselves. By January 1933, the town had printed $6.5k worth of wooden money.

Tenino wasn’t alone in this experiment. During the Great Depression, local currencies saw a golden age. Hundreds of municipalities, business associations, and worker co-ops started issuing scrips. One estimate suggests as much as $1B worth of scrip circulated in the US in the 1930s.

Cash-strapped businesses soon relied on local currencies to pay their employee salaries. One exemplary story came from the publisher of the Springfield Union in Massachusetts, who started paying employees in his own scrip in the 1930s.

The idea: Employees could spend that scrip at businesses that advertised in the newspaper who sent it back to the Union in exchange for ad space, closing the economic loop.

Tenino resident Kathryn Moses poses with wooden currency in 1932 (World Wide Photo / Los Angeles Times; 1932)

Tenino’s currency, in particular, captured the zeitgeist. News of the wooden currency spread first across the country, then the world.

Banks in Chicago started accepting Tenino’s wooden money. Washington Senator C.C. Dill bragged about it to Congress. The Los Angeles Times declared, “Money Now Grows on Trees.” Tourists from as far as India came to Tenino to grab a piece of their own wooden currency. Demand grew so high that collectors started paying $2.50 for a single wooden quarter — a 10x markup.

As Fournier puts it, “It went 1930s viral.”

On January 1, 1933, when businesses in Tenino stopped accepting the wooden currency, US newspapers proclaimed that the town had gone “off the wood and back to the gold standard.”

Can local currencies really save the economy?

Take a look around the globe, and you’ll find local currencies everywhere. Amid the economic fallout from COVID-19, small-town leaders have struck on the same idea as Fournier:

- The town of Castellino del Biferno, Italy — population 550 — started printing a local paper currency nicknamed the “Ducati” in late April to stimulate commerce.

- Mexico’s Santa María Jajalpa sent out about $2k worth of a local currency, called jajalpesos, to help poor residents buy vegetables, chicken, and tortillas locally.

- The Brazilian city of Maricá is making extra money off of a digital local currency known as the mumbuca. Mumbucas are so omnipresent — even city officials receive their salaries in mumbucas — that businesses pay the local government a 2% fee to accept them. That money is funneled into no-interest loans that are offered out to members of the community.

In the US, the local currency movement is more fractured. Plenty of currencies — like Ithaca HOURS (Ithaca, New York) or Bay Bucks (Traverse City, Michigan) — made a splash for a decade or so before petering out.

Local currencies from around the world (via Schumacher Center)

One of the most successful ongoing experiments is called BerkShares, a paper currency founded in 2006 through the nonprofit Schumacher Center for New Economics. Over 400 businesses in Great Barrington, Massachusetts accept BerkShares, and the money is backed through a network of community banks.

Susan Witt, who heads the Schumacher Center, says that this current economic collapse has only highlighted the value of a currency like BerkShares.

Her organization has received a number of requests from municipalities across the country hoping to set up their own currency systems on the BerkShares model; two of them are considering possible next steps.

“It is a very grim time for small businesses. Many won’t survive,” says Witt. “A currency, managed locally, is an elegant tool to address local needs.”

But can local currencies really boost a local economy? The past holds a few clues.

Take the Austrian town of Wörgl, which launched its own schilling in 1932. To keep residents spending, Wörgl appended a 1% monthly fine when residents held onto the notes. By 1933, each Wörgl schilling had circulated 463 times — more than double the circulation rate of Austria’s national currency. Wörgl’s unemployment dropped by 25%, even while unemployment continued to balloon throughout the rest of the country.

Anecdotes like this point to the potential of community currencies — but teasing out a definitive relationship between community currencies and economic resilience is complicated, according to Marek Hudon, a professor of economics at the Free University of Brussels (Belgium).

“There are many shops saying that they have new clients thanks to community currency,” Hudon says, but “it’s extremely difficult to make a causal relationship to this local currency and a real macro-economic impact.”

Hudon co-authored a 2015 review of community currency research and found that about half of “community currencies” (an umbrella term that includes local currencies like BerkShares or Tenino’s wooden dollars) had no measurable macro-economic impact.

But the study also found that in a subset of cases, local currencies could “act as cushions against external economic shocks.” And while their impact may not be widely felt, local currencies are “significant for a small but substantial part of the population”: the economically marginalized.

Joyce Worrell, who runs a small antique shop in Tenino, is one of many small business owners in the town who say they will accept local currency (courtesy of Joyce Worrell)

Francis Ayley, the creator of Life Dollars in Washington state, told The Hustle about a struggling Bellingham woman he knew who borrowed roughly $9k worth of Life Dollars. After 2 years, backed by credit from the community, the woman landed on her feet and started paying back her commitment.

“If she’d gone to the bank and said, ‘Can you lend me $10k for the next 2 years?’ they would have laughed and said, ‘Of course not,’” says Ayley.

Tenino’s wooden dollars are different from many local currencies in that it is temporary: The money will lose its value soon after the town declares an end to its COVID-19 state of emergency.

While the Tenino project might be less ambitious than some of its counterparts, that doesn’t mean its benefits won’t be felt. Fournier says he’s approved at least half a dozen applications for the wooden currency so far and has another dozen to review.

It’s too soon to know exactly what the project will bring. But on a recent Thursday, Fournier sounded optimistic. The money has started trickling into local stores, and many businesses are posting photos of the currency to Facebook.

The project has driven enough local excitement that the Tenino Chamber of Commerce is interested in making the wooden dollars a permanent fixture of Tenino — even after the pandemic passes.

“We’ll run out this program,” Fournier says, “and then we’ll look into having our own city currency.”