In the early 2000s, a new face appeared in America’s elite wine circles.

Rudy Kurniawan was secretive about his past. But the gregarious 20-something quickly made his name known by throwing lavish tasting parties attended by Hollywood producers, wealthy bankers, and tech titans.

Kurniawan seemed to have boundless cash and a knack for finding extremely rare vintage bottles that lifelong oenophiles had only ever dreamed of — 1920 Petrus, 1945 Romanée-Conti, 1947 Château Lafleur.

In a few short years, he would sell off millions of dollars’ worth of his wines to some of America’s wealthiest connoisseurs.

But behind the ever-flowing stream of Burgundies, Kurniawan harbored a dark secret: He was carrying out history’s greatest wine fraud.

And it would take a vengeful billionaire, a French vintner, and the FBI to get to the bottom of the barrel.

The new kid on the block

Little is known about Kuniawan’s early life.

Born Zhen Wang Huang in Jakarta, Indonesia, in 1976, he came to the US on a student visa in the mid-’90s to study accounting at Cal State Northridge.

By 2001, he’d settled in the Los Angeles suburb of Arcadia and developed an obsession with California wines.

Using money he’d supposedly sourced from his wealthy family, he soon turned his attention to expensive French wines — particularly those from the region of Burgundy.

Photo illustration by The Hustle

In the early 2000s, Burgundies weren’t wildly popular in the US. But Kurniawan seemed to sense an opportunity for market growth.

He learned all he could about the wines, talking up shop owners, snatching up 100s of bottles, and keeping detailed tasting notes.

“His average bottle price was probably $400 to $500 per bottle,” Kyle Smith, a Los Angeles shop owner who sold Kurniawan wine, later told documentary producers. “He probably bought $500k [of wine] in the first year.”

Kurniawan’s deep pockets gained him entry into the most prestigious tasting group in Los Angeles: a cadre of prominent, wealthy men — Hollywood directors, music executives, tech entrepreneurs, and real estate tycoons — who called themselves the “BurgWhores.”

Kurniawan wasted no time establishing himself as the leader of the pack.

He began to frequent auctions all over the country, spending as much as $1m/month on wine, according to various news reports. During bidding, he’d thrust his paddle up in the air and leave it hoisted until he won. The price seemed inconsequential.

And Kurniawan liked to share his hauls.

At tasting parties, it wasn’t unusual forJurniawan and his friends to drink through $100k-$200k worth of wine in a single night.

A 2006 profile in The Los Angeles Times titled “$75,000 a case? He’s buying” described Kurniawan as a “young, hip” extraordinaire who’d “upped the industry ante” with his buying power and hobnobbing.

“Auction houses were giddy,” the article’s author, Corie Brown, later recalled in Sour Grapes, a documentary about Kurniawan’s plight. “No one had ever spent that much money that fast.”

Kurniawan placing a bid at a wine auction in the mid-2000s (archival footage, via Sour Grapes)

Kurniawan was introduced to the “12 Angry Men,” a group of wine lovers with “fuck you” money who dined out at fine NYC restaurants, regularly racking up 6-figure bills.

When asked about the source of his money, the enigmatic collector was vague. And after each dinner, he’d request to keep the empty wine bottles.

To his new companions, this was strange behavior. But as long as the vino was flowing, nobody seemed to care.

A seller’s market

By 2006, Kurniawan, then just 30, had amassed a personal cellar so robust that the Calgary Herald declared him the “King of rare wines.” To others, he became known as “Dr. Conti” — an homage to his favorite wine, Domaine de la Romanée-Conti.

In a few short years, he’d gained the trust and respect of some of the nation’s foremost wine critics, scholars, collectors, and buyers.

But more importantly, he’d played a central role in drumming up hype around vintage wines.

According to a 2006 report from Wine Market Journal, the average price of a vintage wine bottle sold at auction increased by 62% between 2001 and 2006. During the same time period, worldwide wine auction sales ballooned from $90m to $300m.

Burgundies, in particular, were a hot commodity: Bottles that sold for $400 just a decade earlier were now courting bids for $13k.

Kurniawan decided it was time to sell.

John Kapon, who helped Kurniawan sell vast quantities of wine, holds a bottle of Chateau Lafite Rothschild (est. value $20k-$30k) at an auction preview in 2010 (MIKE CLARKE/AFP via Getty Images)

Through his high-flying social circle, he befriended John Kapon, an ex-hip-hop producer who ran Acker Merrall & Condit, a boutique wine auction house in NYC.

In January 2006, Kapon agreed to put up a selection of Kurniawan’s wines on the auction block. The collection — dubbed “the Cellar” — featured wines that the market hadn’t seen in years and marketed Kurniawan as one of the country’s most trusted collectors.

“This is a collector who actually inspects his wine,” read the event catalog. “Over the years, and after seeing a number of counterfeit wines, this collector takes exceptional pride in the bottles he has acquired.”

Over a 2-day span, the auction’s 1,742 lots brought in a combined $10.6m in sales.

The auction was so successful that the duo decided to run another one 9 months later. This time, sales topped $24.7m, setting a record for the highest-grossing wine auction in history.

With his proceeds, Kurniawan chameleonized himself into a playboy of epic proportions. He drove a Lamborghini Murciélago, purchased $535k worth of Patek Philippe watches, and bought an $8m mansion in Bel-Air.

But behind the scenes, some prominent figures in the wine space began to question Kurniawan’s rise.

Astute observers noticed, for instance, that he’d sold 10 bottles of 1945 Château Pétrus — a vintage of which only 600 bottles were produced, and only a few dozen were known to still exist.

It seemed highly unlikely that a collector could’ve sourced that kind of haul out of thin air.

Bottles of Pétrus sold by Kurniawan (US Department of Justice)

On the popular forum Wine Berserkers, a thread chronicling the oddities of Kurniawan’s wines swelled to 9k posts. Evidence also emerged that Kurniawan’s uncles, Hendra Rahardja and Eddy Tansil, had embezzled $600m+ from Indonesian banks and fled the country in the ‘90s.

These doubts intensified after Kurniawan’s next few auctions were withdrawn due to questions of authenticity:

- In 2007, a Christie’s auction pulled a lot of Kurniawan’s 1982 Château Le Pin after the company deemed them to be fake.

- In 2008, Kapon’s auction house withdrew $600k+ worth of Domaine Ponsot wine when the vineyard’s owner showed up in person from France and personally called them counterfeits.

“We try our best to get it right,” Kurniawan told a Wine Spectator reporter. “But it’s Burgundy, and sometimes shit happens… I just want the market to get healthy.”

The king of rare wine was hemorrhaging credibility — and things were about to get a lot worse.

A smited billionaire and a pissed vineyard owner

Down in Palm Beach, Florida, the energy billionaire Bill Koch began to realize that he’d been taken for a ride.

An inheritor of one of America’s largest family fortunes, Koch had spent decades collecting a trove of the world’s rarest wines, which he kept in a sprawling cellar underneath his 45k-square-foot mansion.

Bill Koch closely examines a bottle from his collection (Bill Koch, via Berry Bros. & Rudd)

A top buyer at auctions, Koch grew suspicious of counterfeiters and hired authenticators to vet all 44k bottles in his collection. The results were sobering: 5 bottles he’d purchased from Kurniawan at the 2006 New York auction — $75k in total — were fakes.

In 2008, he filed a $3m lawsuit against Kurniawan and commissioned a private investigator to dig into the man’s past.

Around the same time, Laurent Ponsot, the vineyard owner who’d contested the 2008 auction, started to do some digging of his own.

Kurniawan had attempted to sell bottles of 1945 and 1971 Clos St Denis from Ponsot’s vineyard — a wine his family didn’t even start producing until 1982.

After visiting NYC and confronting Kurniawan about the origin of the fake wines, he was left with a sinking feeling that something was amiss.

So, Ponsot embarked on a journey across Asia to try to unearth Kurniawan’s mysterious supply chain.

By 2010, the efforts of these men converged when the FBI stepped in to covertly investigate Kurniawan’s role in the flood of counterfeit Burgundies that had infiltrated the market.

Vintner Laurent Ponsot — whose detective work later proved critical in identifying Kurniawan’s fraud — posed in his vineyard in Morey-Saint-Denis, France, in 2012 (Thierry Esch/Paris Match via Getty Images)

Amid the mounting controversy, Kurniawan struggled to sell his wines at auction.

At a London auction in February of 2012, he attempted to offload 78 bottles of Burgundy wine from the esteemed Domaine de la Romanée-Conti under an alias — but the lot was withdrawn after astute critics noted the serial numbers were off.

Nonetheless, he continued to sell extremely rare wines of unclear origin to private buyers, including:

- A $15.1m sale to David Doyle, the co-founder of QuestSoftware

- A $5.3m sale to Brian Devine, the former CEO of Petco

- A $3.1m sale to Andrew Hobson, an executive at Univision

- A $2.2m sale to Andy Gordon, a Goldman Sachs partner

This apparent success belied a mess of financial woes.

According to court records, Kurniawan’s had debts in excess of $11m. He was defaulting on loans, double-dipping on collateral, and begging his wealthy friends for help.

Where was the money going?

The bust

On the morning of March 8, 2012, half a dozen FBI agents raided Kurniawan’s home in Arcadia.

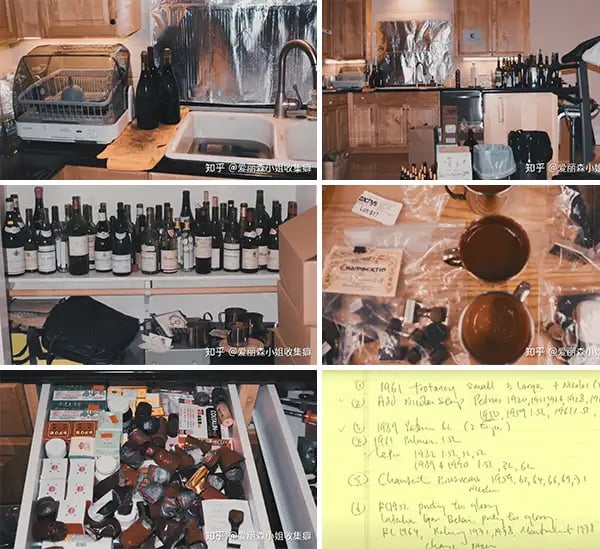

Inside, they discovered an unbelievable scene:

- 200+ old wine bottles in various states of forgery

- 19k+ fake, artificially aged printed labels from the world’s 27 rarest wines, and detailed notes on how to fabricate them

- Buckets full of corks, sealing wax, glue, and stencils

- Rubber stamps bearing the names of famed châteaus

- Formulas for recreating the taste profiles of rare vintages using a combination of much cheaper wines

Photos from the scene of the crime (US Department of Justice)

Kurniawan was arrested on charges of forgery and fraudulently obtaining millions of dollars in loans.

On December 9, 2013, his case went to trial.

Prosecutors laid out the case that Kurniawan was the “biggest and most successful wine counterfeiter in the world,” citing the numerous inaccuracies with the bottles he’d sold (missing accent marks, inaccurate dates, misspellings).

They contended that Kurniawan had kept original bottles from rare vintages he’d polished off and then refilled with a combination of much cheaper wines, using his extraordinary palate to mimic flavor profiles.

He’d ordered labels en masse abroad, then artificially aged them to appear real. For the final touch — the cork — he’d used a blade corkscrew that left no traces of tampering and dipped the top in wax.

The bottles he purported to sell were so rare that many collectors didn’t even know how they were supposed to taste.

During the trial, one expert testified that up to 75% of the fakes that had surfaced on the market in 2006 originated from Kurniawan.

“For a while, the magic show worked. But there was just one problem: There was no magic cellar,” US attorney Joseph Facciponti said at trial. “There were only the defendant’s lies… just a bunch of smoke and mirrors.”

Kurniawan’s lawyer, Jerome Mooney, tried to make a case that the materials discovered in his client’s home were merely ornamental and intended to be used for home decor.

The jury didn’t buy it: 9 days later, Kurniawan was found guilty on all counts and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Evidence presented at Rudy Kurniawan’s trial (STAN HONDA/AFP via Getty Images)

All told, it was estimated that Kurniawan duped collectors out of anywhere from $35m to $150m+ through private sales and auctions.

How was it possible that one man could’ve manufactured millions’ worth of fake wine in his kitchen over a few short years?

Some, like Ponsot (the aggrieved vineyard owner) think Kurniawan had accomplices.

But Mooney counters that the extent of his client’s fraud was exaggerated: “My personal theory is that he just wanted to belong,” he told The Hustle in a recent phone call. “His only entrance to that social circle was wine — wine was his entire identity.”

The aftermath

In November of 2020, after serving 9 years in correctional facilities in California and Texas, Kurniawan was released into the hands of immigration officials.

Last month, with little fanfare, he was escorted onto a plane and quietly deported to Indonesia.

In elite oenophile circles, it was blockbuster news: The saga of the most notorious wine forger in history had finally come to an end.

Some see Kurniawan as a hero — a Robinhood-type figure who duped greedy billionaires and proved that they couldn’t tell the difference between a $500 bottle and $10k bottle.

Others say he irreparably tarnished the collector’s market.

The blog Wine Fraud estimates that the value of Kurniawan wines that are still out in the open market today exceeds $550m. A decade later, the wine auction market is still reeling from the controversy.

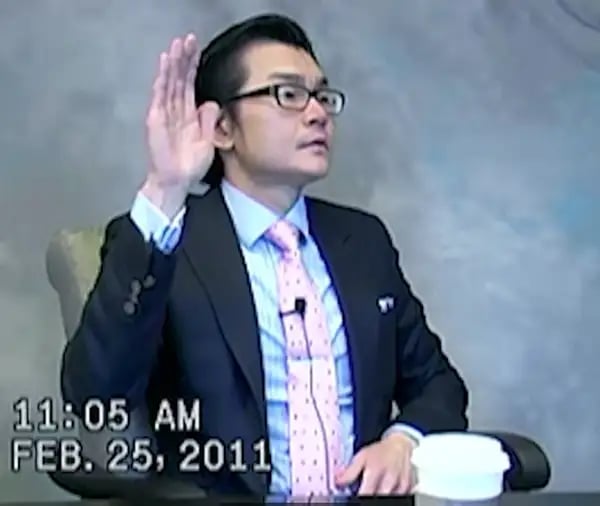

Rudy Kurniawan in a deposition 10 years ago (US Department of Justice)

A free man, Kurniawan is now looking to get back in the game.

According to Mooney, who is still his lawyer, the counterfeiter is still settling in back home and has received many inquiries about working as a wine tasting consultant.

A comeback is in order — and this time, he claims, it’ll be above the table.

“The world,” said Mooney, “will hear from Rudy again.”

Lead photo by Ricardo DeAratanha/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images (photo illustration/animation by The Hustle)