Late last month, a truly bizarre scene unfolded in the market.

GameStop ($GME) — a stock that began the year trading at ~$17 per share — rocketed up to $483, then came crashing back down to Earth a few days later.

The saga began when a bunch of hedge funds (“hedgies”) heavily speculated that GameStop would plummet.

The hedgies’ idea was to short the stock –– or bet against its future success. Their plan was foiled when Redditors and newly minted day traders snapped up millions of shares, momentarily sending the beleaguered consumer electronics retailer “to the moon.”

Short selling can be a bit hard to wade through, especially for new investors. So in this explainer, we’ll touch on the following:

- How short selling works

- How a “short squeeze” can threaten the strategy

- How recent events might affect the future of short selling

Stocks are a non-physical asset and can be a little hard to conceptualize. So, to explain this, let’s imagine that a share of stock is a physical object — say a lamp — that is currently worth $100.

Now, let’s start with what a typical investor does

This is Monty.

He just really likes this lamp and he thinks that it’ll go UP in price. So, he buys it at the current market price ($100) and holds onto it until that day comes. This is called going “long.”

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

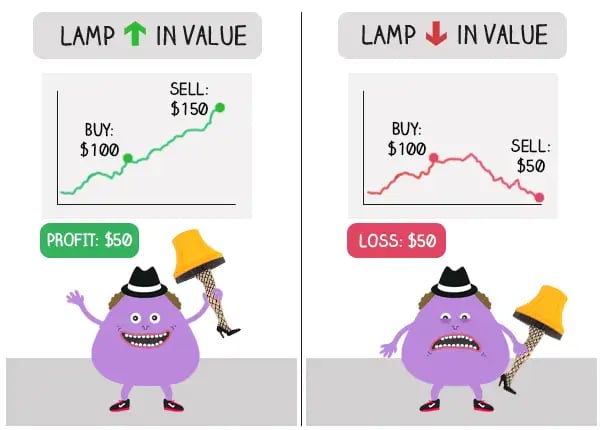

For Monty, this investment will end in one of two ways:

- The lamp will increase in value → he’ll gain a profit

- The lamp will decrease in value → he’ll absorb a loss

He thinks that “lamps only go up,” so he’s bullish about the future.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

But what if an investor thinks the lamp is going to go DOWN in value and wants to hedge a bet against it?

Here’s where short selling comes in

Let’s say there’s another dude named Melvin.

Unlike Monty, Melvin thinks the lamp is way overpriced at $100, and speculates that the market for this ugly thing is due for a big correction in the future.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Short selling is a bit more advanced than a typical stock transaction. To do it, an investor has to have something called a margin account that lets him borrow against his investments.

It’s high-risk, high-reward — and usually, only more seasoned traders with lots of capital (e.g. hedgies) screw around with it.

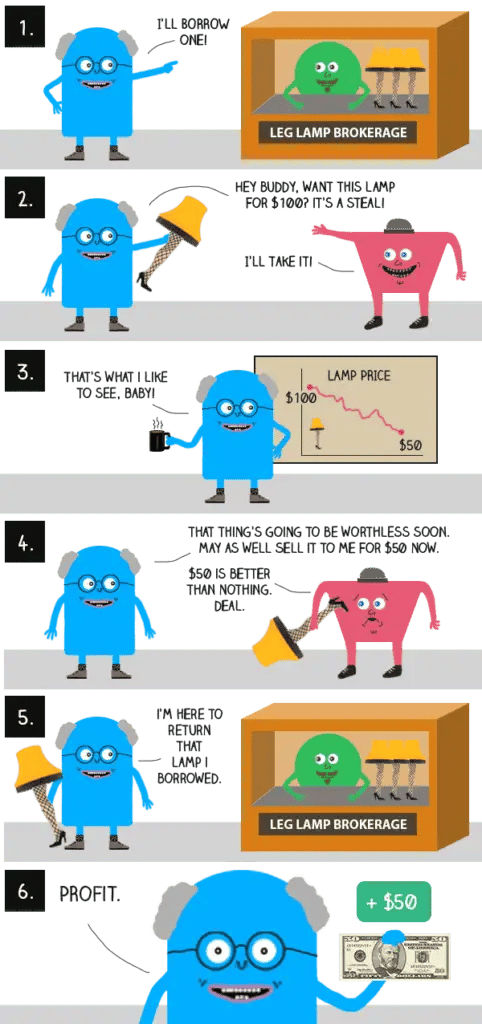

But in simple terms, here’s how it works:

- Melvin borrows* a lamp from a lamp broker

- Melvin immediately sells the lamp at the current market rate

- Melvin sets a date for when he thinks the price will go down

- Melvin buys back the lamp for a lower price

- Melvin gives the lamp back to his broker

- Melvin pockets the difference

* Borrowed shares usually come from a broker’s own inventory, or from the account of one of the broker’s other traders. In return for the loan, a short seller pays the broker interest and commission fees.

If the price of the lamp goes down before Melvin has to return the lamp to the broker, his short works out perfectly.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

But what happens if the value of the lamp goes UP?

Let’s go back to Monty, our traditional “long” investor. The lowest the lamp can go to is $0 — so the maximum amount he can lose is the $100 he originally invested.

By contrast, Melvin’s risk is infinite.

In theory, there is no limit to how high a lamp’s price can go. It might 10x in price, and he’ll be responsible for paying the broker back before the expiration date.

This uncapped ceiling can be a big threat to short sellers like Melvin.

Imagine that Melvin and a bunch of his friends decide to short lamps. They all borrow lamps from their brokers, sell them for $100 apiece, and speculate that the price will drop to $50.

But then Elon Musk Tweets out a photo of a leg lamp in a SpaceX shuttle and it suddenly becomes the hottest buy in America.

The price of a leg lamp skyrockets to $200.

Melvin and all his buddies begin to realize the price won’t drop by their expiration date, so they panic and start buying back lamps at a loss to pay back their brokers before things get even worse.

The influx of short sellers buying into the market drives the price of lamps up even more — $500 … $800 … $1k!

This dreaded event is called a short squeeze.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle (Musk smoking weed: The Joe Rogan Experience, via YouTube)

A short sqeeze ends up being terrible for Melvin, who anticipated a big dip in the lamp market.

Conversely, it’s a major payday for an investor like Monty, who believed in the future of his lamp. The heights his lamp reaches in the squeeze exceed anything he ever initially dreamed of.

The future of the short

So, how does this all tie back in with what happened to GameStop and other “meme stocks” last month? Here’s a simplified review:

- A bunch of Wall Street folks shorted GameStop stock.

- A bunch of retail investors and Reddit users gobbled up GameStop stock, causing an artificial spike in price.

- Short sellers scrambled to get out, causing a short squeeze.

- Like most short squeezes, the boom was short-lived and the stock came tumbling back down to pre-squeeze levels.

In the end, a few shorters got badly burned — most seriously, Melvin Capital, which lost ~$4.5B (53% of its assets) and had to be bailed out by a fellow hedgie.

On the other side, some Redditors and retail traders made handsome “tendies” by riding the squeeze. But most of those who got in late (including Barstool’s Dave Portnoy) either ended up deep in the red, or have pledged to hold to the grave.

The situation has cast yet more doubt on the efficient market hypothesis — the idea that stock prices are rooted in the actual inherent value, based on available information.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle (@zzcrockett)

And what could this mean for the future of short selling?

Many analysts are predicting that the GameStop epic will result in:

- More bubbles, fueled by hype in online communities and the accessibility of trading apps.

- Less short selling, as investment firms shy away from the volitility these bubbles could create.

Some short selling firms have already reevaluated their entire strategy.

The prominent short seller Citron Research — run by a man who has described himself as a patroller of “fraudulent and over-hyped stocks” — recently announced that it will cease publication of its flagship short reports and shift to “multibagger opportunities for individual investors.”

One thing is certain: Melvin will be thinking twice about speculating on his next lamp.