On the go? Listen to our discussion of this story on The Hustle Daily Show podcast.

A few weeks ago, a client from Alabama asked Bernard Ewell to appraise a work of art by Salvador Dalí.

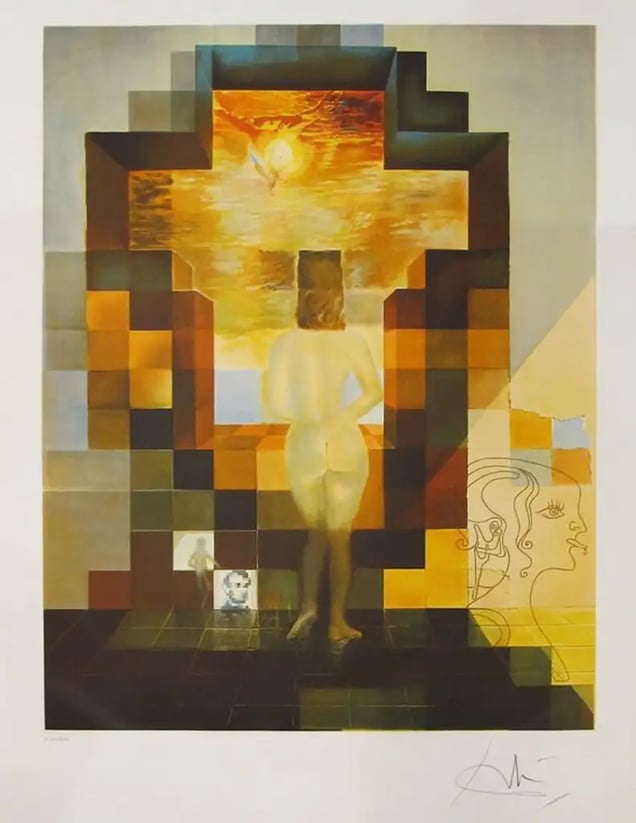

It was one of the artist’s most recognizable pieces, Lincoln in Dalívision, a mosaic print of Dalí’s wife, Gala, that resembled the face of Abraham Lincoln from a distance. The work came with a letter from an attorney attesting to a copyright transfer between Dalí and a publisher, so the client assumed it was legitimate.

Ewell shared the bad news: The print was published by two brothers in Alabama as part of a well-known series of fake reproductions. The signature wasn’t real, either.

It was hardly an unusual consultation, or result. Although Dalí has been dead for 34 years, Ewell receives several inquiries almost every day from owners who believe they own one of the artist’s works but doubt its authenticity.

“I don’t see how I can ever retire,” Ewell, who is 79, told The Hustle.

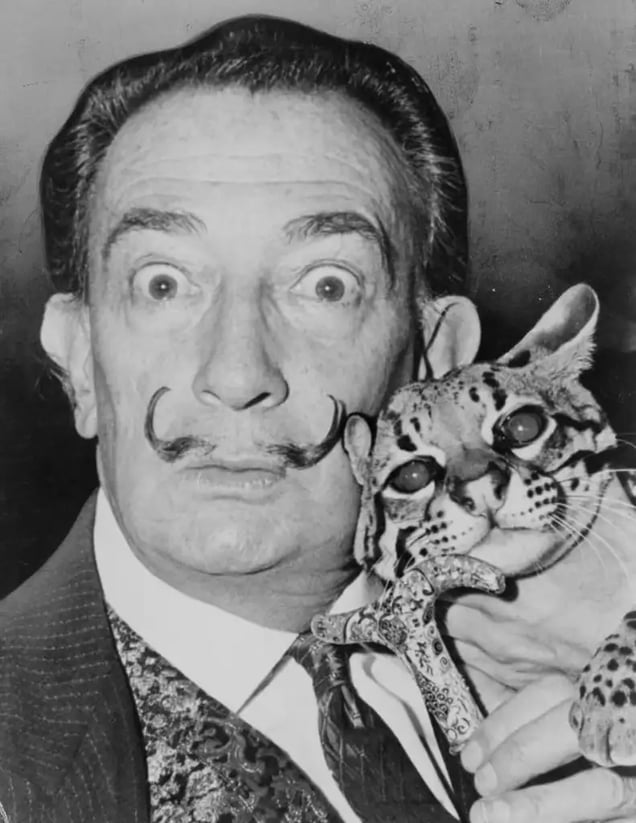

Dalí, the surrealist Catalan painter, is one of the most recognizable names in art, known as much for works like The Persistence of Memory (the melting-clocks painting) as for his eccentric personality (he once filled a Rolls-Royce with cauliflowers and kept an ocelot as a pet).

Ewell explains the difference between original and fake Dalís in this video. (The Hustle)

In a career spanning more than 50 years, Dalí produced a vast number of paintings, etchings, lithographs, and sculptures. But fake reproductions of his art constitute a larger market.

In the 1980s, during an art investment bubble, experts believe hundreds of thousands to millions of fake Dalís began to circulate, leading to $625m to $1B in sales of fake Dalí art in the US. Worldwide, fraudulent sales may have reached $3B.

The fraud led to prison sentences for unscrupulous art dealers and gallery owners, sunk the value of many authentic Dalí works, and continues to confound hobbyist art collectors — like Ewell’s client in Alabama — who often find out their family’s prized art is worthless.

High art and high finance

On Nov. 14, 1934, when Salvador Dalí visited the US for the first time, the American press greeted him as soon as he disembarked from an ocean liner. Where, they asked, did he draw inspiration for his art?

Dalí’s answer was absurd: “Two broiled lamb chops on my wife’s shoulders.”

That single statement, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle commented, “made Gertrude Stein seem, by comparison, as prosaic as the Encyclopedia Britannica.”

Dalí poses with ocelot Babou. (Library of Congress)

The fascination from Americans signaled to Dalí and Gala the potential for building a lucrative brand.

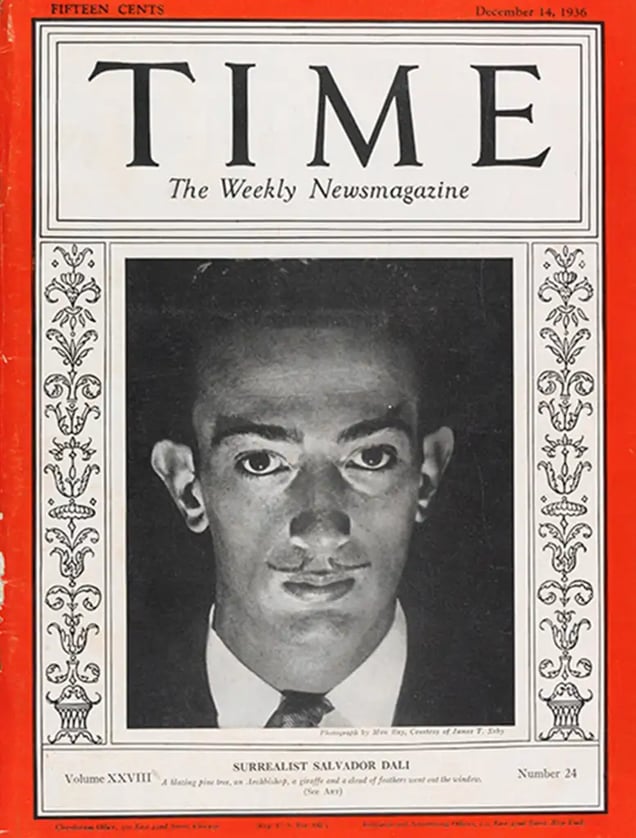

- Dalí landed prominent exhibitions and a cover story in Time, gaining a reputation in the US as the embodiment of surrealism and striking up a relationship with a Cleveland manufacturing exec who purchased hundreds of paintings.

- Gala sought up to 500 contracts per year for her husband, securing deals to appear in ads for companies like Braniff International Airways and Alka-Seltzer.

“(Dalí) was completely money obsessed, to the point of a mania,” said Noah Charney, an art historian and author of The Art of Forgery.

The artist’s appetite for money — as well as his embrace of Nazism — made him a black sheep to many colleagues. French surrealist André Breton famously called Dalí an anagram of his name: Avida Dollars.

Dalí on the cover of Time in 1936. (Time via Twitter)

But the US never turned its back on somebody with dollar signs in their eyes. By the 1950s and 1960s, it was clear the demand for Dalí’s work exceeded the supply.

So Dalí, Gala, and others in Dalí’s inner circle devised a solution: prints. Lithographs and etchings took less time to finish than paintings and could be reproduced as limited series.

There were two categories of Dalí prints:

- Fully original: Dalí created the images himself on a printing plate and signed a limited series of prints. Originals sold for up to $3.5k.

- Legitimate prints: Some limited-edition lithographs were made by licensed publishers copying a watercolor of Dalí. These were not technically original, although they were marketed as such and approved and signed by Dalí. They could sell for nearly as much as the fully original prints.

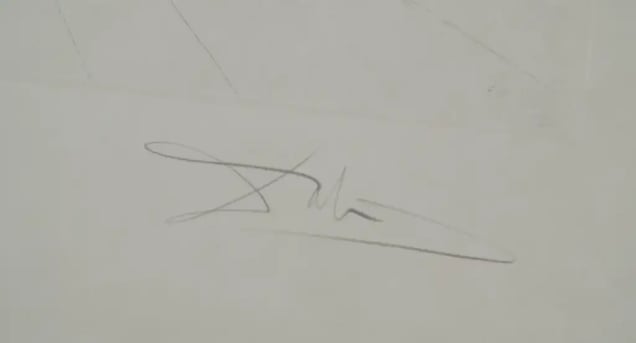

Dalí ensured a steady flow of prints by signing his name on thousands of blank sheets of paper before he knew what would be printed on them. (The signature was worth ~$40 on its own.)

Members of his inner circle, some of whom exploited Dalí for profit, once told the Wall Street Journal Dalí would sign blank sheets “every two seconds for an hour without stopping.”

A legitimate signature from Muse of Astronomy. (Christopher Roybal for The Hustle)

The prints, the signatures, and the commercial contracts kept the dollars rolling in. Beyond, the magazine of the St. Regis Hotel, noted Dalí was as much “high finance” as he was “high art.”

But in the 1970s, the artist’s health declined, and he became a recluse for the next decade. Dalí stopped creating prints. He stopped signing his name. And yet, in a stroke of real-life surrealism, the world, and especially the US, was about to see more art attributed to Dalí than ever before.

The art of investment

At the Center Art Galleries in Honolulu, John Proctor’s job was to shadow visitors in the showroom. When they looked at Lincoln in Dalívision, he began his sales pitch, handing them a fact sheet revealing reported increases in value for Dalí’s art and setting them up with a “closer” to convince the visitors to spend as much as $11.5k for the print — enough, at the time, for a down payment on the median US home.

“It was easy to sell art to the tourists,” Proctor told The Honolulu Advertiser in 1980. “Once you tell them they’re going to make money, they get hot for the stuff.”

It was the era of Reaganism and Wall Street greed, and art was now being marketed as an investment. Many gallery owners told customers a piece of art by the likes of Picasso, Miró, or Chagall would never lose value.

Dalí proved irresistible to Americans dreaming of easy money and prestige:

- He was recognizable, the guy people remembered from their college art history course or saw Mike Wallace interview on “60 Minutes.”

- He was prolific, having signed thousands of prints.

- He was sick, and salespeople promoted the likelihood of his death (he died in 1989) as an opportunity for the market to spike.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Dalí works, previously available through exclusive auction houses and well-connected dealers, turned up in mainstream American galleries like Center Art Galleries, gift shops, and even classified ads in the Los Angeles Times ($8.1k “OBO” for a Lincoln in Dalívision print from some guy named Guido).

The used-car-style sales tactics at galleries tailored to the middle class were worrying enough. But there was a bigger problem in the Dalí market. With demand skyrocketing, a third type of Dalí print began circulating: fakes.

There was one authorized edition of Lincoln in Dalívision prints and far more fake editions. (Dalipaintings.com)

Some fakes were unlicensed photomechanical reproductions of his lithographs and etchings. Other fakes were printed reproductions of his paintings that were never intended to be printed as a series, or completely fabricated works that resembled Dalí’s style.

Because many of Dalí’s original and legitimate prints were turned into limited-edition series (sometimes with a vague number of authorized prints) and he had been sloppy with his signature throughout his life, it was hard to tell the difference between a real print and a fake print that had been copied an unlimited number of times.

As doubts about the mass infusion of Dalí art trickled out in lawsuits and newspaper stories — and Dali’s lawyer suggested ~100 Dalí titles were being circulated as fakes — many reputable galleries and auction houses, like Christie’s, refused to sell Dalí limited-edition prints.

Dalí, holed up in his Catalan home, even went on the record to stem the tide of fakes. In 1986, he signed an affidavit saying he hadn’t lent his signature to anything since 1980, and the only things he signed in 1980 were items like contracts and checks.

But a lack of expertise allowed the fraud to perpetuate. Salespeople at mainstream galleries received little to no training, and most customers, largely clueless about art, trusted certificates of authenticity and Dalí signatures. They were also reluctant to cooperate with law enforcement agents who had been chasing leads.

“A lot of people buying these were lawyers, doctors, nurses, teachers — and they were embarrassed,” Jack Ellis, a former postal inspector, told The Hustle.

Sellers such as Center Art Galleries reaped the rewards. In 1984, owner William Mett claimed the chain was the largest art seller in the US, selling tens of millions of dollars of art annually. His client list included the Saudi royal family.

Tracing the fakes

A few years earlier, in 1980, an Alaskan who had bought three Dalí prints from the Center Art Galleries asked Bernard Ewell to appraise them. Ewell, the son of a top official at the Art Institute of Chicago, had been around art all his life and was in the early stages of a career as an appraiser.

The Dalí request led him to converse with fellow appraisers, dealers, and museum curators. They all knew something was fishy, but almost none of them knew how to tell the difference between a real and a fake or cared to learn.

“I really concentrated on Dalí because nobody else was doing it,” Ewell said.

Ewell picked up subtle clues from the texture of the three Dalí works from Center Art Galleries, noticing the ink wasn’t thick enough to be an original lithograph print.

Later, he learned that many fakes were printed on special paper from the French manufacturer Arjomari, and an Arjomari employee told him that the company had changed its main watermark in 1980. Because Dalí stopped signing prints after 1979 a fake Dalí could be spotted by examining the watermark.

The discovery aided Ewell in his work — and would soon assist federal prosecutors in court.

Ewell examines a fake Dali (Christopher Roybal for The Hustle)

Agents with the FTC, Postal Inspection Service, and Department of Justice followed the crumbs from lawsuits, criminal complaints, and investigative reporting by Lee Catterall to build a case against the Center Art Galleries, raiding the business in 1987.

- Mett and his curator were convicted on dozens of counts of wire and mail fraud for selling $113m of fake Dalí art from 1977 to 1989.

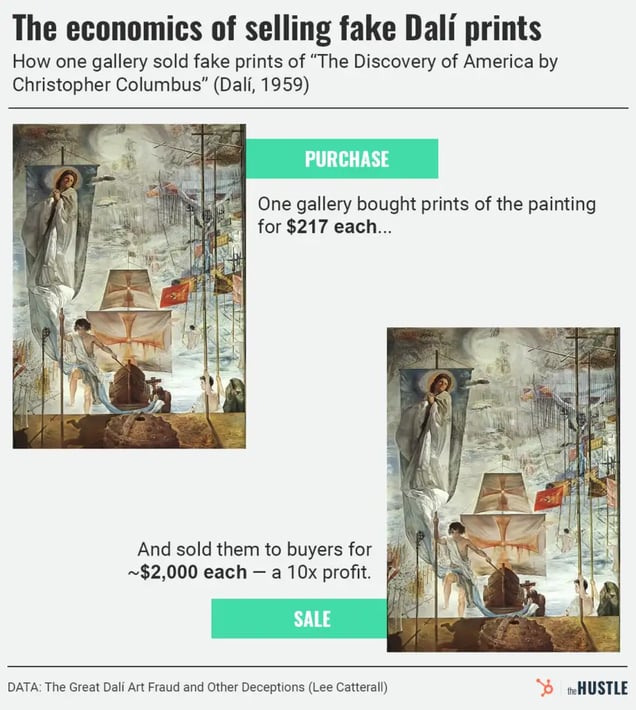

- Prosecutors revealed that Center Art Galleries typically bought fake Dalí copies for $135 or less from a distributor and sold them for ~$1k-$21k each. In reality, each was worth ~$25-$50. (Mett did not respond to an interview request.)

- Ewell testified as an expert witness for the prosecution.

The feds also uncovered fraudulent art sales in places like Denver, New York City, Phoenix, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Alaska. Some operations were classy galleries; others were boiler rooms where telemarketers cold-called doctors and dentists, pumping and dumping Dalí prints over the phone.

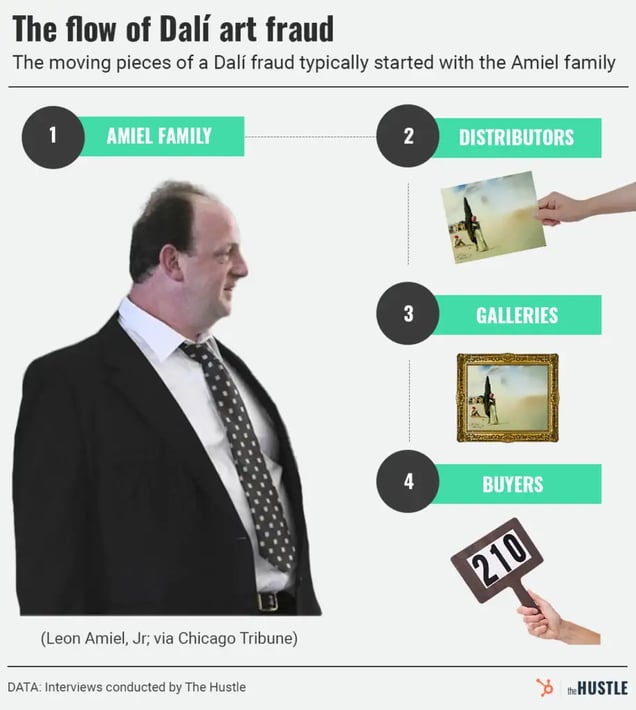

The sellers often claimed they were unaware they were selling fakes, but many ended up pleading guilty. Most of their illicit art came from the same producer on Long Island — a French Legion of Honor recipient named Leon Amiel, an authorized publisher of Dalí lithographs and an acquaintance of the famous artist.

But, as Ellis (the postal inspector) and partner Jim Tendick discovered through an investigation named Operation Bogart, Amiel went rogue, pumping out enough unauthorized copies to produce ~80%-90% of the fake Dalís sold in the US — from boiler rooms in New York to the Center Art Galleries in Hawaii.

Amiel died in 1988, but his wife, two daughters, and granddaughter, a Boston College student who was adept at forging the Dalí signatures, continued the family business.

Undercover agents infiltrated the Amiel family’s business. In July 1991, Ellis and a few dozen agents raided the Amiel headquarters, an old carpet warehouse near the beach.

They piled palette after palette of art into postal trucks, altogether ~75k prints, including ~50k attributed to Dalí. Soon, Ewell was hired to examine a stash of the Dalí prints, wheeled into a “war room” at the postal inspectors’ New York office in a giant mail cart.

To nobody’s surprise, he found that every one of them was fake.

The everlasting fraud

These days, you never know where a Dalí will turn up — or if it’s really a Dalí.

A few years ago, David Spiegel, a former lead attorney with the FTC who investigated art fraud, went to an auction held by a religious institution in Washington, DC. Sure enough, they auctioned off a Dalí.

“I can’t tell you this Dalí was fraudulent, but I had never seen a legitimate Dalí up to that point, and this was an image I had seen at least a hundred times,” Spiegel said.

On Facebook, members of art identification groups post photos of supposed Dalí prints — signed, numbered, and paired with certificates of authenticity — that they’ve bought at Goodwill or on eBay, been gifted by family members, or found in storage units. One woman picked a Dalí out of the trash. The group’s members suggested that she probably should’ve just left it there.

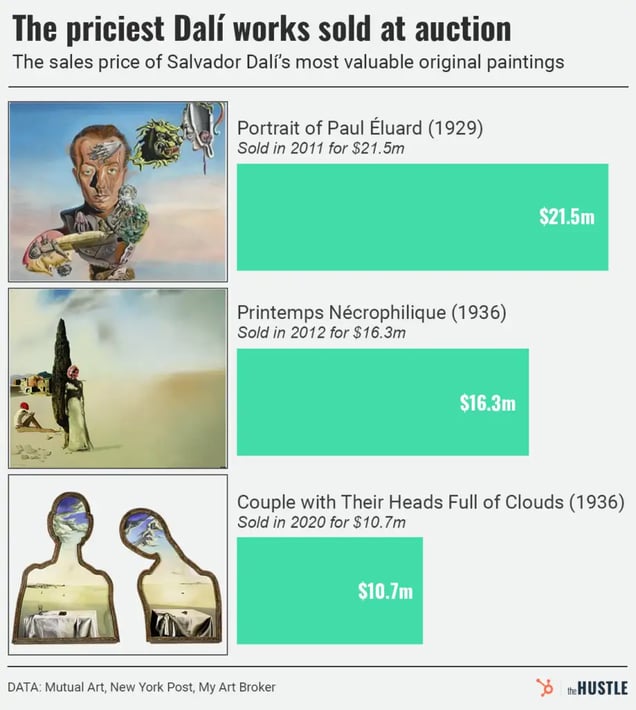

The confusion has depressed the market for real Dalí prints. While his paintings have surged in value, the original and legitimate prints of his lithographs and etchings — which many galleries still won’t touch — are worth ~$4k-$6k, according to Ewell. Many original prints sold for roughly the same amount in the 1980s.

In more than 40 years focused on Dalí, Ewell has appraised ~58k Dalí-attributed prints and deemed slightly over half to be fakes. Despite the fraudulent sales peaking decades ago, Ewell has viewed more prints attributed to the artist in the last 20 years (~38k) than he did in the ’80s and ’90s (~20k).

Back then, his clients tended to be young parents who believed a fancy piece of art would diversify their investment portfolio and legitimize their entry into the upper middle class. They were duped into making a costly mistake.

Now, his clients are that generation’s grownup children, many who saw their parents proudly display their print and brag about owning a Dalí.

And these clients, Ewell said, often learn “that Dad got screwed.”