I didn’t mean to drink the maker movement Kool-Aid. It happened by mistake. I was swept away by how impressive Maker Media is, and how it’s succeeded by taking the opposite route from other media enterprises.

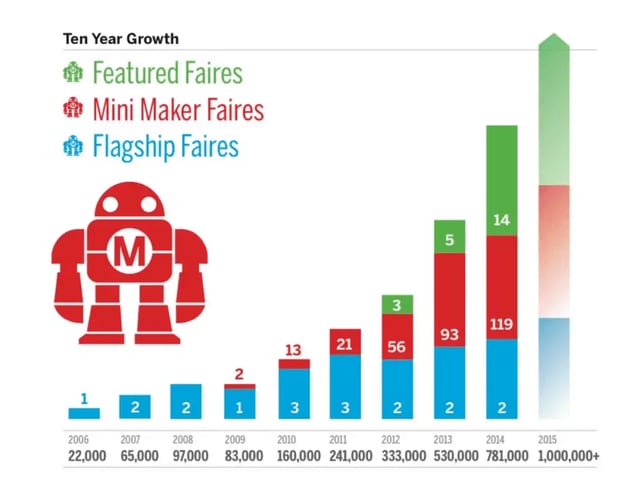

Today Maker Media is a multipurpose machine. The company publishes a number of magazines and books each year, have a robust web presence, a large YouTube presence, and sell products online on Maker Shed. And they host Maker Faires, festivals that celebrate the “DIY mindset,” showcased through art, electronics, and craft projects. The first was held in 2006. There are now 151 worldwide.

For reference, the 2015 Maker Faires had over 1.1 million visitors — the same audience size as Taylor Swift’s 1989 world tour.

Maker Media holds a number of additional events a year; free to attend Maker Camps designed to inspire children, and MakerCon’s, which give professionals the tools they need to run full-time maker businesses.

I went to Make: Magazine’s pop-up Christmas store in San Francisco to meet Dale Dougherty, the founder of Maker Media. He founded Make: Magazine a decade ago, and unwittingly godfathered a movement that’s spread across America, culminating in a Maker Faire held on The White House lawn last year.

The definition of a maker is someone who creates or produces things, and this can be anything: tech startups, crafting, robots, woodworking. Basically, it’s participating in a hobby that’s proactive, instead of reactive. Building an LED dragon vs. watching The Real Housewives.

My notebook was full of scribbled questions: “Ask him about flying drones on his vineyard”, “How does it feel to be 60-years-old in a city with an emphasis on youth?”, and “Why are you publishing a physical magazine when everything is digital?”

But then I met Dougherty and his new CEO, Gregg Brockway, elected in 2014, and lost my game face. The sheer enthusiasm and passion pouring out of these dudes was overwhelming, and I was filled with the type of mushy squishy feelings I normally suppress.

These guys were like skinny Santas, spreading worldwide goodwill by boosting the brain power of all adults and children.

“People are looking for an alternative to Christmas,” Dougherty said. “It’s too much about stuff and an obligation… it’s not empowering. With Make we’re getting back to what play is about, and that it’s about the kids. This is important.”

When Dougherty smiled, his cheeks turned rosy, and I had a weird desire to hug him.

But how did the maker movement grow from a tiny operation into a worldwide phenomena that has an entry in the Urban Dictionary?

The birth of the maker movement

Back in 2005, this was just an experiment that Dougherty was determined to try. He was a technical writer, working at O’Reilly Media, and publishing Hacks – a series of books for hardware hackers.

“The idea for Make: Magazine came from my experiences with the Hacks books,” he wrote on LinkedIn. “I recognized that hackers were playing with hardware and more broadly, they were looking at how to hack the world, not just computers.”

He pitched this as “Martha Stewart for geeks.”

He wanted Make: Magazine to be a thick compendium of maker knowledge. I asked why he didn’t choose to create something digital. He looked a little embarrassed. “It’s a magazine about physical things,” he said, so a physical copy seemed natural. “It’s still a good business model, as people collect them,” he explained.

The first magazine featured life hacks and projects. This included a guide to creating a magnetic stripe reader, a Lego machine that solves Rubik’s Cubes, and how to use kites to take aerial photos.

It had 181 pages, cost $14.99, and was published four times a year. Dougherty predicted 10,000 in sales for the first year. He was wrong.

70,000 copies (total) of the first three issues were sold. 35,000 people subscribed. By year three, circulation was 130,000. The original editorial to advertising ratio was 90-to-10.

“It was a very much an upside down model,” Dougherty told FOLIO Mag in 2005. “We focused on what people want to read about, and getting advertisers we could develop relationships with and who get what we are doing.”

The following year, Dougherty put on the first Maker Faire in San Francisco. This gave people hands-on time with robotics, electronics, and techie projects. 22,000 people attended. There are now 151 faires, and they get over a million visits a year.

The global maker picture

Maker Media is the company that coined the word “maker”, but the term is now ubiquitous to anyone experimenting with their own builds and crafts. Around the same time that Maker Faires came into being, so did another website pivotal to the maker movement, Instructables.com.

Created by MIT engineer Eric Wilhelm, Instructables launched in 2006. His goal was to provide step-by-step instructions for a myriad of projects. The slogan was “share what you make.” Instructables has hundreds of thousands of projects that include everything from make your own Evil Dead LED lamps to Jabba the Hutt Menorahs. The company monetizes with a freemium model (you pay to remove ads) and were purchased by Autodesk in 2011 for $32 million, according to the New York Times.

Today, Instructables.com is ranked 548 out of all the websites in the world, and 318 out of all American websites by Alexa.

Another collaborator in this space is TechShop, which opened its first location in 2006. The slogan is “Build your dreams here.” TechShop offers visitors access to equipment like 3D printers, laser cutters, and wood lathes for set fees. They have 10 locations across America and some of today’s hottest startups have been created in their workshops. This is where Jack Dorsey built the first prototype of Square.

“This is a revolution,” CEO Mark Hatch told Fortune. “If you can imagine it, you can make it. And that’s new to the world.”

Interest in the maker movement has risen steadily since 2008, according to Google Trends data.

“When I started I could find makers, but – what’s an indicator of the movement – a lot did not identify as makers,” Dougherty said.

Today, people are proud to call their activities “making” and there are now hundreds of places to see the efforts of their ingenuity.

The educational evolution of makers

Dougherty believes that the future of makers needs to be helped through education. He argues that young people need to be helped to develop their creative and technical abilities, and that this is something they are now accustomed to.

“When kids play Minecraft they expect not just to play, but also to evolve,” Dougherty said. For those who don’t play, Minecraft lets you build 3D structures in a virtual world, and you can design and adapt them as you gain experience. Over 21 million people have downloaded the game.

To enable this type of learning, Dougherty has invested in Maker Ed, a nonprofit he co-founded in 2012. The slogan: “Every Child A Maker.” Their goal: to enable all children to experience making, and providing access and opportunities to all communities.

Dougherty’s a fan of “informal education” and said that it needs to grow on a “grassroots level.” He emphasizes that it’s about teaching the parents as well; it’s fun, and they’re both learning skills. And it’s necessary that they get it. They’re the ones with the purchasing power, after all. He also set up Maker Camp, a free program that engages kids in hands-on learning. This has been supported by Google, NASA, and The White House.

“There’s a recognition amongst parents now that maker skills are essential,” he said. And with so many high-paying jobs requiring these types of skills, you can see why.

“There’s high interest in [making] because the price points are down dramatically,” CEO Gregg Brockway interjected. “You can buy mini-computers like Raspberry Pi for under $10. That was inconceivable a few years ago.”

Makers at Christmas time

2015 is the first year that Maker Media has set up a physical store. Their Christmas pop-up in San Francisco is right by Union Square, the premier shopping district. Their store is bright and airy and features a number of products that you can buy on Maker Shed, their online shopping portal. Large Parrot drones are stacked by the window, and small skittering robots zoom across the floor.

There are DIY LED menorah kits to buy, machines that let you paint with light, and kits for building retro arcade games. Visitors can play with a number of items before buying, a good chance to go hands-on with things they’ve only seen online.

Dougherty said they selected products they’ve seen at Maker Faires around the world. There are Makeblock robotics from China and littleBits from Canada. And Gakken, a weird Japanese book/model hybrid that lets you build your own mini planetarium. It has no English instructions.

The two men walk me around some of their favorite products. Dougherty’s a fan of The Useless Machine, a programmable box that performs one action when you hit the button… it shuts the box. “It does nothing, but you can make it,” Dougherty said. Brockway said that was the first thing he built with his son.

Then there’s the Roominate electronic dollhouse, designed at engaging girls. “It’s a challenge getting girls into electronics,” Dougherty said. “Craft is one way. The appeal is it’s a stealth way for teaching them how to use tech to do things.”

“The store is a way to introduce people into making,” said Brockway. “We are mission driven here.” In part, the reason for opening the store was due to the shift in purchasing behaviour made by people who are looking for something more “real” instead of the “hot” throwaway toy.

“It’s an experiment,” Brockway said. Will they reopen next year – or open more stores globally? The economics of this season will factor in, Brockway admitted. But ideally, he’d like too.

So far, the best selling products have been drones, 3D printers, the 3Doodler 2.0 and the programmable L3D Cube Kit.

The future of Maker Media

So how will Dougherty’s self-titled “catalogue of knowledge” fare over the next decade? Maker Media’s looking to the future, and to ensure its movement continues, the team is focused on building out new initiatives.

In 2014, the White House held a Maker Faire, and President Obama publicly declared America a “nation of makers.” This year President Obama established a “week of making” in June 2015. In April 2015, Maker Media launched Maker Space, an online community for makers to share their projects and discuss the reasons behind them.

Tune in for the first-ever White House Maker Faire starting at 10am ET: http://t.co/xw80gvKQSL #NationOfMakers pic.twitter.com/8XfvX9OHLe

— The White House (@WhiteHouse) June 18, 2014

It’s hard to run a media company today, especially one with such an emphasis on physical products. In 2009, AdAge reported that Make: Magazine circulation was 125,000, post-recession. But this grew to 315,000 in 2013, according to Make. In 2014, this was reported as 300,000. Numbers are relatively stable, a surprising result for a media company today. Dougherty said that revenue was around $15 million in 2013. In June 2015, Maker Media secured $5 million in funding, which they’re using to expand their network.

Dougherty envisages a future where makers build more healthcare and wearable products. “Not just experimental but experiential,” he said. “We’ll all be 3D printing limbs and being more immersive.”

He told me about a creation he saw at Tokyo Maker Faire. A maker had rigged a mattress with sensors and turned it into a video game controller. The screen was on the ceiling, and you operated it by rolling around. “It’s stupid, but it has applications in real-world healthcare,” he said. Imagine this being adapted for people with mobility issues or health problems.

The maker movement takeaway

Makers are taking over America. But it’s nothing to fear; in all likelihood you’re a maker too. You might not realize this, but it’s true. Remember, the definition of a maker is anyone who is creating, and as long as you’re building something or striving to make something new, that means you. The word might connote stereotypes of nerds supergluing circuit boards in basements, but this is far from the truth.

There are an estimated 135 million makers in America – that’s over half the population. The fact that this many people are involved in creating something new – on an individual or group level – is undeniably exciting.

Hell, the nicest CEOs I’ve ever met have fully sold me on this movement, and I’m proud to be a part of something bigger. And Dougherty’s success proves that you don’t have to follow the established path to get to your end goal. Sometimes printing a physical magazine in a digital world will just turn out to be a stroke of genius.

We’re all makers now, whether we’re designers, doodlers, or engineers working on the next Stripe prototype. Together, we really can create something special.

Merry Christmas!