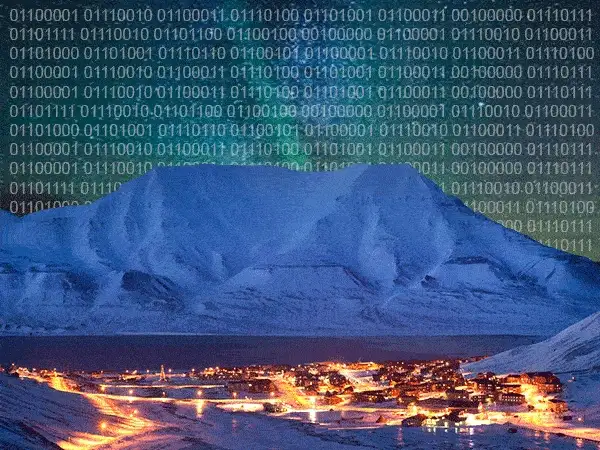

Deep in the Norweigan arctic, on the ice-encrusted island of Spitsbergen, life stands still.

The surrounding lands of the Svalbard archipelago are sparse and desolate. It is a place where there is a 1:10 polar bear to human ratio, where the sun doesn’t rise for 4 months per year, and the northern lights dance across the sky.

But on the side of a mountain in Spitsbergen, there’s an abandoned coal mine. And inside — some 250 meters below the Earth’s surface — you’ll find a steel vault that contains an archive of film encoded with hundreds of thousands of open-source projects from around the world.

Run by a for-profit company called Piql, the Arctic World Archive is aiming to preserve the world’s digital materials — music, literature, and lines of code — for 500+ years.

Recently, Github, an open-source coding platform, donated it’s entire trove of code to the archive — some 21 terabytes of data posted by millions of users since 2008.

Most press accounts have dubbed the Arctic World Archive a “doomsday vault.” The archive prefers the term “vault of hope.”

Either way, it’s an effort to incubate our data from human and environmental catastrophes in the long-term. And it may just be our best shot at telegraphing our present-day story to future generations.

The company behind the Arctic World Archive

Preserving data through climate change, potential nuclear warfare, and whatever else the next 500+ years has in store for us might sound like a daunting task.

But this kind of long-term thinking is the lifeblood of Piql, a 20-person tech company based in Drammen, Norway.

Scenes from Spitsbergen (Arctic World Archive, GitHub)

Building an apocalypse-proof archive was not always Piql’s plan.

Founded in 2002 by a former engineer named Rune Bjerkestrand, the company — originally “Cinevation” — began with the mission of preserving film.

Bjerkestrand knew that Hollywood had a long history of losing its masterpieces due to inadequate preservation efforts and wanted to test a new approach: instead of leaving films on black-and-white archival film, he thought to turn each film into a chunk of scannable code.

He invented a way to boil down each film into a magnifiable binary code — a series of 1s and 0s — that, together, look a bit like QR codes. Then, he stored a patchwork of those codes in a film cartridge called a piqlBox.

Piql started making deals with film companies in the US, Norway, and Sweden. As The Hollywood Reporter explained in 2008, the beauty of Piql was its speed: other devices took 15-18 hours to encode a 20-minute clip; Piql could do the job in ~30 minutes.

But Bjerkestrand soon began to see other use cases for his technology.

Piql, he realized, could sequence almost any digital product into scannable 1s and 0s. And after the sequencing was done, it could be preserved in the box — conceivably, for hundreds of years. While other storage devices required constant updating, Piql’s method was all hardware-based: if the box survived, so would its QR code.

Top: Piql’s silver halide film, encoded with binary; bottom: a piqlBox (Piql)

Piql’s long-term thinking became more ambitious in January 2008, when conservationists and agricultural researchers launched the Global Seed Vault — a Svalbard-based facility designed to protect crop diversity in case of global catastrophe.

Bjerkestrand thought, ‘Why not do something similar for our digital data?’

With the help of a Norwegian mining firm, Piql built out the Arctic World Archive in a decommissioned coal mine, right down the road from the Global Seed Vault.

In 2017, it opened for business.

Who is the archive actually for?

Piql is a for-profit company and allows anyone to store something in the Arctic World Archive — for a fee. Its chief selling point is the long-term survival of material.

For starters, Svalbard, where the archive is based, has been called “one of the most geopolitically secure places in the world.” It’s not only rugged and remote but has been a demilitarized and independent region since 1925, incubating it from warfare.

The boxes the film is stored in are virtually indestructible. The company tested them against electromagnetic pulses, extreme nuclear radiation, and -196°C (-321°F) — and they’ve persevered. One Norwegian industrial research institute estimated that a piqlBox could last 500+ years without degrading.

And the film itself, which is coated in silver halide crystals and iron oxide, has a purported lifespan of 500 to 2k years.

“On a film, it just looks gray. But if you put it under a microscope, you can see all the data points,” Piql’s managing director, Katrine Loen Thomsen, tells The Hustle. “We call it self-contained. It’s not reliant on any technology that may or may not be around in the future.”

Top; Piql’s managing director, Katrine Loen Thomsen, at the Arctic World Archive; Bottom: Thomsen handling some piqlFilm reels (Piql)

Most of Piql’s clients are museums, governments, or large companies. Among its stores:

- A digitized copy of “The Scream” by Edvard Munch, sent in by the National Museum of Norway

- A set of essential documents held by the Vatican Library, including a digital copy of Dante’s original manuscript of The Divine Comedy

- Duplicates of historical records kept in the National Archives of Mexico

- The complete run of the German TV show, Galileo

Earlier this year, the archive got its largest addition to date when the software development company, GitHub, donated its entire trove of code — some 21 terabytes of data, including modeling systems, apps, and website designs. It required 186 rolls of film.

But the company is also working on an affordable small-data model that will encourage individuals to store data there. Individuals will pay a one-time sum based on a period of time (50 years vs. 500 years).

The archives lay deep inside a decommissioned coal mine in the arctic circle (Inside Over)

The Arctic World Archive might be the most fully-formed project of our moment, but it is far from the only long-term storage project to enter the public consciousness:

- The Long Now Foundation is building a $42m clock in a Texas mountain that will keep time for a purported 10k years.

- The Future Library is scheduling books for publication 100 years from now.

- The Arch Mission Foundation partnered with SpaceX to launch Isaac Asimov’s Foundation into space. Tucked inside the glove compartment of that famous red Tesla, it’s expected to orbit the sun for 30m+ years.

- The ceramicist Martin Kunze has spent years engraving futuristic messages on clay tablets and storing them in an Austrian salt mine.

- The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine is attempting to preserve a digital archive of the internet’s billions of web pages.

This all might sound promising, but there are reasons to be skeptical.

Can long-term storage really last?

As a society, we don’t have a very good track record with lofty, long-term storage projects. Take, for instance, time capsules.

Entrepreneurs have been selling the promise of historical preservation to the public since the early 19th century. In 1876, a magazine publisher named Anna Diehm charged individuals to have a photo included in her 100-year capsule, alongside signatures from members of Congress and other artifacts.

But when President Gerald Ford opened Diehm’s capsule in 1976, his disappointment was palpable. As the historian Nicholas Yablon later recounted, one of the president’s aides said, “Mrs. Diehm did not seem to have a very good concept of what would be important and interesting a hundred years later.”

After the opening, Diehm’s photos went straight into an archive. When Yablon visited in 2010, he realized that he was the first person to request them since.

As President Ford found out, the contents of most time capsules are underwhelming (AP; 1976)

Many archivists attest that we’re living in a time when preservation is crucially important.

File formats are changing so rapidly that material from just a few decades ago has already slipped out of reach. Some caution that we might be living through a “digital dark age:” we’re putting more data than ever into the world, but it’s entirely possible that less of it than ever will actually survive to the end of the century.

As Google’s data manager, Rick West, said in 2018: “We may [one day] know less about the early 21st century than we do about the early 20th century.”

The Arctic World Archive is offering up a solution. And it isn’t the only one.

There is a whole micro-industry of preservation-focused companies, with names like Arkivum, StorCentric, and PreserveOn. Many of these startups advise corporations on how to preserve information for long periods of time in those companies’ own vaults. Piql is one of the few that is actually offering up its own space.

But how realistic are these visions? And even if we succeed in storing data for 500+ years, will future generations be able to decipher its significance?

“Just making data available in its original form may not make it useful to users,” says Ruth Duerr, a data management expert at the Ronin Institute. “Just having an image of a shoe worn by George Washington isn’t going to do much good, especially if you don’t know it was worn by George Washington.”

GitHub transferred a 21-terabyte repository of its code to the Arctic World Archive earlier this year (GitHub)

Piql does have a system in place to explain to future generations how to read the QR codes. On each piqlBox is a set of instructions, readable with a magnifying glass. For good measure, it’s written in English, Arabic, Spanish, Chinese, and Hindi.

But there is only so much context the Arctic World Archive can provide.

Lacking granular context, will future generations be able to work out that they’re looking at the code for a food delivery app, and not a self-driving car?

The COVID factor

Thomsen (Piql’s managing director) says that the Arctic World Archive only allows new deposits about 2x per year. Otherwise, she tries to leave the space alone.

The next deposit, scheduled for October, is the archive’s first true COVID-era project.

Over the last few months, Brazil’s Museum of the Person has been working on a video series called “My Pandemic Diary” — a collection of everyday people recording their personal stories of the pandemic.

In a month, these stories will be locked away in Svalbard.

And in 500 years, if all goes according to plan, future generations will know of our collective misery.