For 30 years, Keahi Seymour pursued a dream.

That dream wasn’t to play in the NFL. It wasn’t to front a rock band. It wasn’t to grace the silver screen. It wasn’t to cure cancer. It wasn’t to walk on the moon, discover Atlantis, or lead a nation.

Keahi Seymour wanted to invent a boot that enabled him to run like an ostrich. And he wanted to share it with the world.

But this story isn’t about boots: It’s about the relentless pursuit of a vision in the face of repeated setbacks. What drives someone to stick with an idea for 30 years? To give up everything for a device that seems, to most people, inconsequential? To sacrifice hundreds of thousands of dollars in life savings, time, and opportunity cost?

And can something really be called a failure if the journey was self-fulfilling?

An idea strikes

Like other young lads, Seymour spent his youth in England drawing sketches of cars, hoverboards, and model planes — anything that “moved fast and looked futuristic.”

But on a fateful day in 1987, the 12-year-old saw a TV show about kangaroos that would change the course of his life.

“They were talking about how these hyper-fast animals store elastic energy in their Achilles tendons,” he recalls. “And I immediately thought, ‘Why can’t a human use that same spring-like energy to run faster?”

He grabbed a piece of paper and drew out his grand vision: A 1980s running shoe with a pivot, and a lever attached to a big spring with rubber bands.

He called it the ‘Bionic Boot.’

Seymour was soon consumed by the idea. His “mates” recall him spending hours sketching out different iterations of the device throughout grade school. His mother fed his obsession by taking him to a Leonardo da Vinci exhibit that expounded on drawing inspiration from the natural world.

“I started really deeply researching biology and nature,” says Seymour. “I found out that the ostrich was the fastest bipedal animal [it runs at 43 MPH] and started looking into its physiology, how it moved.”

The first build

At 17, Seymour was tasked with designing a technology product for a school project.

Until this point, the Bionic Boot had been more of an ethereal pipedream than a tangible device. But the project, which required students to design a physical invention from start to finish, gave Seymour his first chance to make a full-fledged prototype.

The aim of his design was to give humans (who are plantigrade, or flat-footed) the mechanical advantage of fast digitigrade animals (which walk and run on their toes). He’d achieve this by raising himself a foot off the ground on a set of levers attached to 6-10 big rubber springs.

When activated with a step, the lever would flex back behind the heel; elastic energy stored in the rubber “tendons” would recoil, catapulting him up to 4 feet off the ground, and elongating his stride to 7 feet in length.

The first iteration wasn’t pretty. Seymour utilized a hodge-podge of equipment he found lying around: An old rollerblade boot, metal struts, and a rusty lever — all disconcertingly lashed together with a tangle of bungee cords.

Before a small crowd of curious students, he strapped them on and bounded across the school parking lot. They fell apart after a few strides.

“Everyone was laughing,” says Seymour. “But in those few strides, I could feel the power and speed. I knew I had something special.”

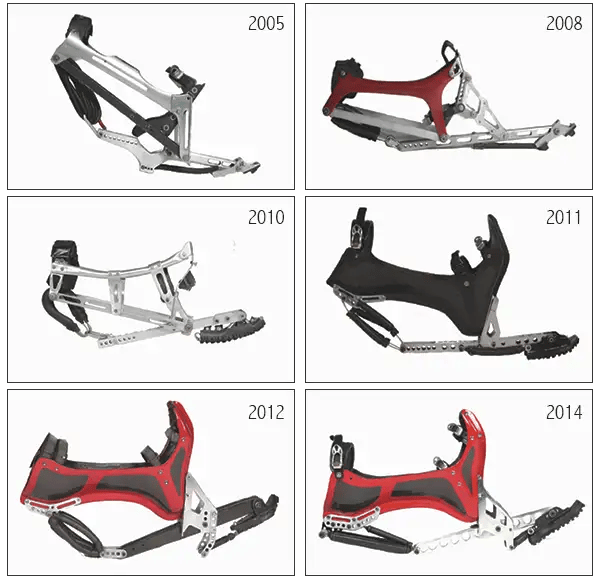

Seymour enrolled at Coventry University to study transportation design and soon shifted his focus to designing cars. But it wasn’t long before the Bionic Boot beckoned again.

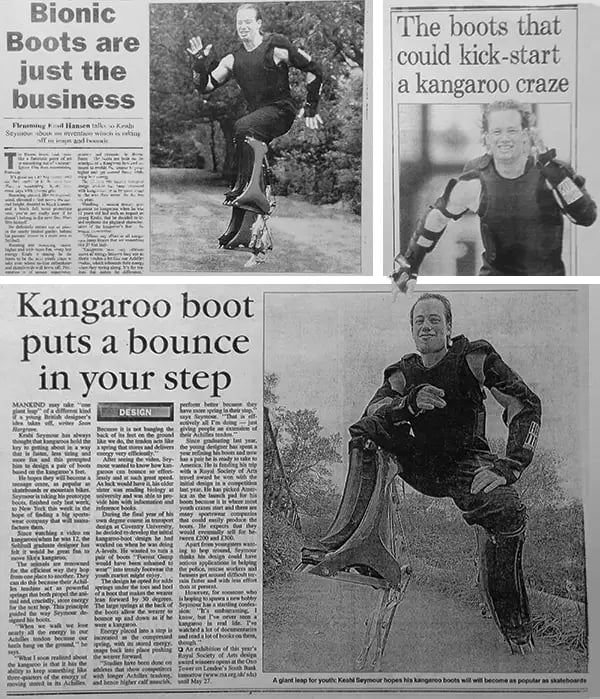

For his final year “thesis,” he was asked to design a product that catered to “youth crazes” — something new, novel, and transportation-based.

Though Seymour’s aim with the Bionic Boot was to mimic the “experience of running fast like an animal,” he realized it could be branded as a form of environmentally-sound, all-terrain transportation. Once again, the boots became his project.

The stakes were high. His instructors would select the best projects and submit them to a national design competition put on by the Royal Society of Arts.

“Unfortunately, I got a failing grade,” says Seymour. “So I decided to submit it myself.”

Seymour drove to the London competition and walked into a room full of England’s design czars: Product designers from Land Rover, Aston Martin, and Lotus sat stoically at a 30-foot-long table. Snobbery filled the air.

“I clapped my hands, and my buddy, Chris, walked out in the boots,” recalls Seymour. “All of a sudden, it was as if the designers turned to schoolchildren: They all stood up, taking pictures, marveling, murmuring.”

Miraculously, the Bionic Boot won the competition, secured a small grant of £1,125 (~$1,500 US), and picked up a little press.

College came to an end and Seymour’s friends all settled into 9 to 5 jobs with high-end car manufacturers. For a short time, he joined them, taking a role in Jaguar’s styling department. A promising future lay before him.

But he couldn’t shake the exhilaration he’d felt bounding across the school parking lot. The Bionic Boot consumed his mind like a virus.

So, in 1999, Seymour packed a suitcase full of shoe molds, springs, and speargun rubber, and ventured to the foggy shores of San Francisco.

Going to California

At the time, California was a mecca for young entrepreneurs in the outdoors sector. After all, it was the birthplace of the first fiberglass surfboard, the first urethane skateboard wheel, the boogie board, and the mountain bike.

San Francisco seemed to be a fertile testing ground for Seymour’s futuristic boot, and a prime location for his target customers: “Well-to-do adventure-seekers in their mid-30s who had tried every type of extreme sport and wanted something new.”

“I’d take them out for a run around the city and people would lose their minds,” he says. “Everywhere I went, people would say, ‘What the hell is that!”

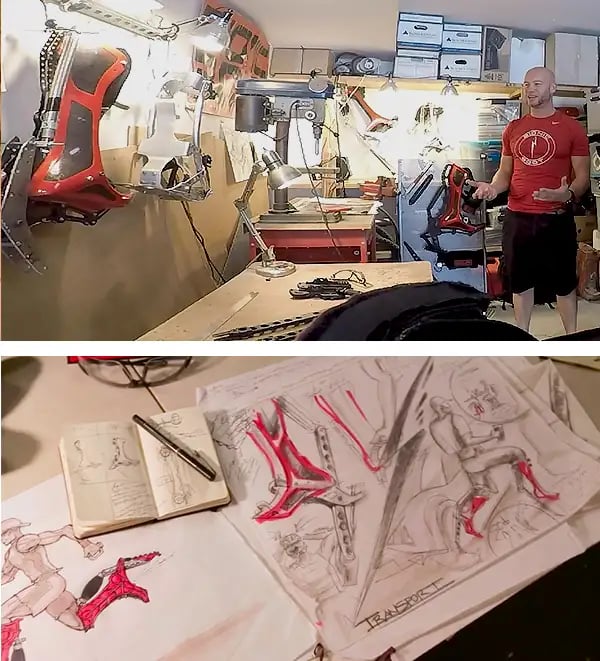

The garage of a Potrero Hill apartment became his mad scientist’s lab; his bathroom became a makeshift carbon fiber oven. Everything was painstakingly made by hand with a drill, an angle grinder, and a hacksaw.

“It looked like Doc Brown’s house from Back to the Future,” he says.

He sourced parts from Metal Supermarkets, a specialty store in Hayward, California that sells things like aircraft-grade 6061 aluminum. He hired a lawyer and secured patents in 15 countries around the world. He spent countless nights blasting emails to companies and investors in an effort to raise funds.

Meanwhile, Seymour worked 6 nights a week at bars and nightclubs — Matrix, Infusion Lounge, The Tipsy Pig. Few people knew about his side-hustle.

“Nobody in my life, even my girlfriend at the time, could understand my obsession,” he says. “I was completely consumed. And I knew my clock was ticking. I needed money… I need investors and partnerships.”

A break and a letdown

A year passed. 5 years. A decade. Despite his efforts, Seymour wasn’t able to convince investors that the Bionic Boot was worth taking a risk on.

By 2014, Seymour had constructed more than 200 prototypes of his Bionic Boot. He managed to increase max speed from 15 to 25 MPH, reduce weight from 10 to 6 pounds, and achieve minor celebrity on the streets of San Francisco.

Periodically, his roommate’s grandma would come by to hassle him: “You still workin’ on those boots, Keahi?! When are they gonna start making some money?”

By this point, he’d invested his entire life savings — more than $200k — and tens of thousands of hours in the boots. His life, his essence, was this invention. But the payoff he’d envisioned didn’t come and he had to make a decision: “Do I keep funding the boots, or do I let them die?

He decided to take his creation to the New York Maker Faire. Fortuitously, an impromptu Make Magazine interview with him was posted on YouTube and went “viral.” Overnight, his inbox was flooded with media requests.

Seymour was branded as “The World’s Fastest Man,” the “Bionic Man,” a slew of other hyperbolic monikers. He was flown around the world to appear on TV shows — Spain, France, England, Denmark. He was asked to race a train in Japan, an ostrich in Los Angeles, and an Olympic hurdler in China. He ran across Manhattan in 12 minutes.

Though the boots became a part of his personal aura and gained him international recognition, they still weren’t seen as a viable product — even with 8k emails from interested buyers.

Many parties were interested in learning more, including SRI International, DARPA, Intel, and even the US Special Operations Command (SOCOM). But this interest never translated to a partnership, grant, or investment.

“Companies just didn’t want to take a risk on something that wasn’t proven, or that didn’t have an existing market,” he says. “Nobody wanted to be the first to take a big risk.”

At the time, the media attention inspired a slew of knock-offs: A Korean company replicated the boots and developed partnerships with 10-15 online retailers. More egregiously, a Chinese firm nicked Seymour’s design, mass-produced the product, and sold it under the “Bionic Boot” name on Amazon.

Though he’d spent a small fortune securing international patents, Seymour didn’t have the means to fight infringements.

The Bionic Boot, it seemed, had reached a hitch in the road.

The crossroads

Today, Seymour’s apartment is still littered with the remnants of Bionic Boot prototypes.

“Some people work on old hot rods or bikes,” he says. “I work on my boots. That’s my passion.”

But after nearly 30 years of dedication, he’s toying with the idea of letting his invention go. He tells me I’ve reached out to him at an interesting time in his life — a moral and emotional crossroads.

“I’m starting to think the boots are dead in the water,” he says. “I can’t sell them. It’s my life-long passion, but I don’t know what to do at this point.”

Seymour faces another big setback: His patents are expiring in a few months, stripping him of the little leverage he has left to strike a manufacturing deal.

He’s been toying with new ideas that might be more “monetarily viable:” A carbon fiber articulated snowboard is currently “cooking” in his bathroom.

Though the Bionic Boot — the invention he’s been obsessed with since he was 12 years old — is at an impasse, he’ll never fully abandon it. The boots have been there with him through the trial and error, the tribulations, the long years of letdowns and bilked meetings. They are one and same, welded together like a steel lever.

This weekend, somewhere in the hills of Pacifica, Seymour will bound down a rocky path with the jaunty agility of an ostrich.