On a summer day in 2019, Daniel Schreiber opened his mailbox to find a threatening letter from one of the world’s largest telecom companies.

In the letter, Deutsche Telekom AG (the parent company of T-Mobile) accused Schreiber’s small insurance startup, Lemonade, of trademark infringement. Schreiber was confused: He hadn’t used T-Mobile’s name. He hadn’t appropriated the company’s logo or tagline. Hell, he wasn’t even in the cell phone business.

But as he read on, he realized his “crime” was using the color magenta.

In recent years, companies like T-Mobile have achieved something once thought to be legally impossible: They’ve successfully trademarked individual colors.

When a color becomes synonymous with a brand — think robin egg blue jewelry boxes, brown delivery trucks, or orange scissors — a company can claim a certain form of “ownership” over it.

But how is it possible for a single corporation to call dibs on a color? And what effect does this exclusivity have on its competitors?

A colorful history

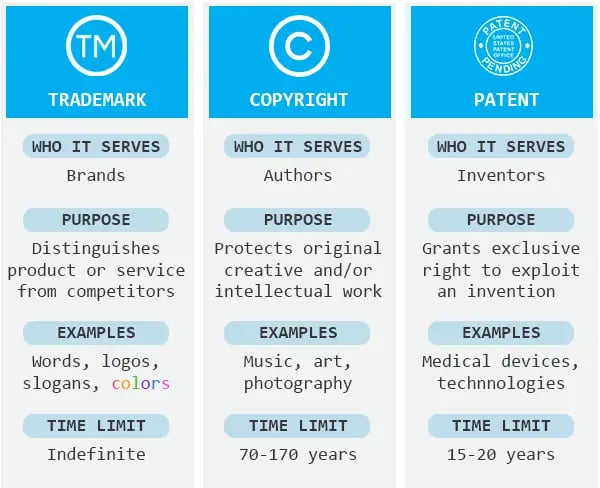

Under the umbrella of intellectual property law, the 3 most common applications are the trademark, the copyright, and the patent.

While corporations routinely file all of these, they use the trademark to (quite liberally) protect anything integral to their brand. Under legal doctrine, this might be “any word, name, symbol, or device [used to] identify and distinguish” a company’s good or service from its competitors.

When a trademark is granted, it gives a company the exclusive right to use that intellectual property in its respective industries.

Note: Though trademarks are indefinite, they still need to be renewed every 10 years. (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

For many years, a color did not, by itself, qualify as a trademark.

Though companies had successfully trademarked combinations of colors (e.g., Campbell’s soup labels), the US Patent and Trademark Office shot down attempts to trademark a single color. John Deere, for example, would not be permitted to lay claim to the color green in the farm equipment industry.

Scholars maintained several arguments against issuing single color trademarks:

- Color depletion theory: Only around 1,867 solid Pantone colors exist; if brands all claim a color, we’ll eventually run out.

- Shade confusion theory: It would be hard for the consumer to determine the difference between slight shade variations of colors claimed by brands.

But everything changed when this stuff came along:

Owens-Corning fiberglass insulation in its trademark pink-dyed hue (Pixabay)

That, dear readers, is a piece of fiberglass insulation (the stuff that goes behind our walls) from a company called Owens-Corning.

In the late 1950s, Owens-Corning was facing steep competition from other fiberglass insulation companies. At the time, all products were the same “naturally tan” hue; to distinguish itself, Owens-Corning decided to infuse their product with dye.

For the next 30 years, the company used its unique pink insulation as a marketing tool: It adopted the slogan “think pink,” used the Pink Panther as a mascot, and spent tens of millions of dollars advertising the color.

In 1985, after a 5-year legal battle, Owens-Corning became the first company in American history to successfully trademark a color.

Ten years later, a second company, Qualitex, went all the way to the Supreme Court to defend its right to trademark its signature green-gold dry cleaning pads. The court ruled that color could, indeed, serve to identify a brand — and in doing so, opened up the floodgates for companies to file their own color trademarks.

What does it take to trademark a color?

In the decades since that Supreme Court case, a number of companies have successfully trademarked single colors.

Tiffany & Co. trademarked its famous blue in 1998 — the same year UPS trademarked its “Pullman Brown.” 3M secured its signature canary yellow color for its Post-it notes, Deutsche Telekom AG protected T-Mobile’s famous magenta, and Fiskars has one for orange scissor handles.

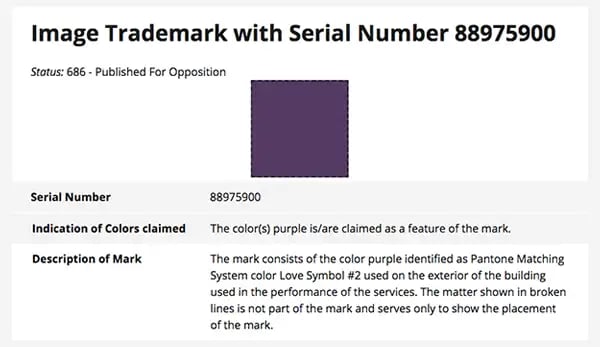

There are even a few you wouldn’t expect: The Wiffle Ball, Inc. has a trademark on yellow for use in bats, and the estate of the late musician Prince currently has one pending for the color purple.

These trademarks aren’t exclusive to businesses, either. The University of Texas at Austin (Pantone 159) and The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Pantone 542) both have protections on their school colors.

A few of these companies, like Cadbury, have since lost their color trademark in legal disputes (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Plenty of brands trademark certain colors that might appear in conjunction with a logo (think, for instance, McDonald’s red and yellow, or Facebook’s blue). But these companies have done something different and far rarer: They have trademarked literal swatches of color.

“Usually a company does this when its business model relies, to some extent, on a particular color,” says Jeffrey Samuels, a professor emeritus at The University of Akron School of Law. “It will trademark a color to prevent other companies from using it.”

An important distinction, adds Samuels, is that a company with a color trademark only “owns” the color in connection to particular goods or services.

Take, for instance, the purple trademark from Prince’s estate, Paisley Park Enterprises. The trademarked image is the color purple alone — no words, no logos, no other form of branding. If granted, it will give them a claim to the color purple for use in live music venues. Purple alone, they claim, is enough to ID their brand.

A trademark filed by Paisley Park Enterprises seeks to secure a shade of purple (Pantone color “Love Symbol #2”) for use in musical performance (Justia)

To successfully secure such a trademark, a firm must prove that a single color:

- Achieves “secondary meaning” (distinguishes a product from competitors and identifies the company as the definitive source of the product)

- Doesn’t put competitors at a disadvantage by affecting cost or quality

- Doesn’t serve a functional purpose

This last piece, says IP lawyer Robert Zelnick, means that “a color really has to be quite arbitrary” to be trademarked: It can’t be essential to the production of the product or serve any utilitarian purpose.

Sometimes, proving all of his can be extremely challenging.

General Mills, for instance, has twice failed to secure a trademark on yellow for its Cheerios box, on the grounds that the color isn’t synonymous with the brand since too many other cereal companies use it in their branding.

Pepto-Bismol’s attempts to trademark pink were thwarted when a court deemed that the “therapeutic” effect the color had on customers was “functional.”

The color wars

As the CEO of Lemonade learned, companies that are granted color trademarks often go to great lengths to enforce them in court — and competitors often challenge their right to monopolize certain hues.

TOP: T-Mobile’s ex-CEO John Legere went above and beyond to embrace the brand’s magenta hue (Twitter); BOTTOM: A diagram of colors from the T-Mobile/Lemonade incident shows the variance in colors that brands claim to “own”

Over the years, these controversial trademarks have resulted in dozens of lawsuits relating to color “ownership:”

- In 2002, Mattel brought suit against MCA Records for, among other things, allowing the band Aqua to use its trademarked pink color on its album cover for the single, “Barbie Girl.” The judge famously advised both parties to “chill.”

- In 2010, Hershey sued Mars for using orange on the packaging of a peanut butter candy bar. The suit was later dropped.

- In 2011, Louboutin accused Yves Saint Laurent of infringing on its trademark red shoe soles and won.

- In 2015, toolmaker DeWalt won a $54m judgment against a competitor that copied its black and yellow colors, though it was later tossed out on appeal.

But one company has been particularly protective of its color trademark.

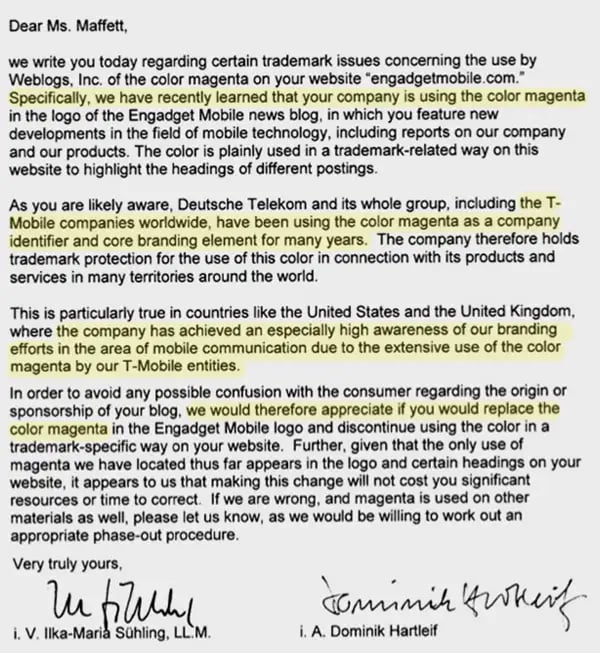

T-Mobile’s parent company, Deutsche Telekom AG, has spent at least 12 years attempting to prevent competitors — some large, some small — from using magenta.

Though its trademark covers only a specific variation of the color (Pantone Rhodamine Red U), the company has expanded its definition of magenta to encompass a variety of surrounding hues. Since Deutsche Telekom has its hands in so many projects, it has also been able to defend its trademark in industries outside of telecommunications, ranging from fashion to healthcare.

In 2008, it went after the rival European wireless carrier Telia. A few months later, it demanded that the tech blog Engadget drop magenta from its mobile logo. In 2014, a judge ruled that AT&T subsidiary Aio Wireless couldn’t use magenta because it would confuse T-Mobile customers.

A letter sent by T-Mobile’s parent company to Engadget, demanding that the blog stop using the color magenta in its logo (Engadget)

Its latest victim, Lemonade, has complied with T-Mobile’s demand by changing the color of its marketing materials in Germany, where Deutsche Telekom AG is based. The company has also filed a motion in Europe to “invalidate Deutsche Telekom’s magenta trademark.”

Making changes like this can be costly — especially for bigger firms that spend tens of millions of dollars on marketing and branding strategies.

But legal fees can also rack up for the companies that constantly trawl for color trademark violations, begging a question:

Is trademarking a color worth all the effort?

When a company files a trademark in black and white — say a simple logo — the trademark is actually protected in all color variations by default. Nobody can, say, take the McDonald’s red and yellow logo, make it purple and green, and claim it as his own.

So, why would a brand go through all the trouble of trademarking a color when they likely already have so many other protections?

“You only see brands do this when the color is critical to the brand, or sales, or the way the product is marketed,” says Zelnick, the IP lawyer.

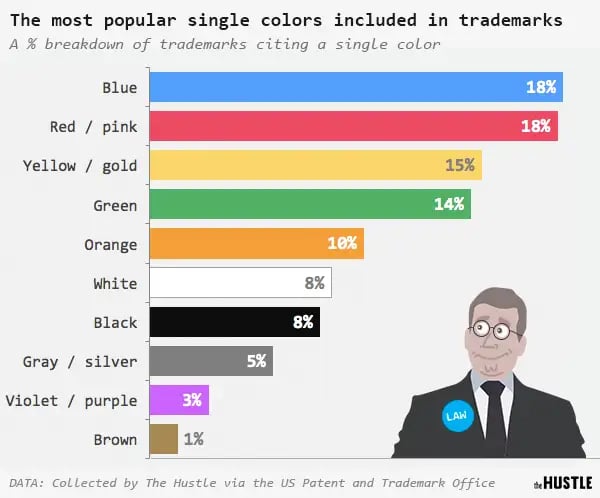

Across all trademarks (including logos), blue is the color of choice (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Most marketers are aware of the effect color has on consumer behavior. Surveys and studies have shown that:

- 62%-90% of a consumer’s initial judgment of a product is based on color.

- 52% of consumers say the color of packaging is an indicator of quality.

- Color increases brand recognition by up to 80%.

So, if you’re thinking about making your entire brand one solid color, go ahead and try your luck. Just don’t pick magenta.