Shortly after the clock struck midnight on New Year’s Day of 2018, Josh Kline closed his eyes and vowed a resolution: He’d sign up for a gym. He’d go every day. He’d lose the paunch and reclaim his former glory.

Yes, he was 6 beers deep and full of carne asada. But dammit, things were different this year: He was going to do it!

A few days, and a few inspirational Instagram posts, later, the 32-year-old New Jerseyan found himself at a local big-name gym, inking a $650 annual contract. Sans the hidden fees, that worked out to a little under $50 per month — a steal, he figured, for 365 days of value.

But by early February, his commitment began to wane. “Every day” became every other day; every other day slipped to twice per week… once per week… zero times per week. At year’s end, his attendance tally looked something like this:

Kline’s story is familiar. “Getting more exercise” is routinely the most common New Year’s resolution — and every January, gyms bulk up their staff and prepare for an infusion of fresh blood.

There’s just one problem with this: Joining a gym, while admirable, is generally one of the worst investments you can make.

The reasons for this are rooted in the way we make commitments for self-betterment, the core business model of the fitness industry, and even behavioral economics. But before we get into all that, let’s take a look at the bigger picture.

Drop and give me $700

In the United States, 60.8 million people (~1 in 5 adults) have some kind of membership to one of the country’s 38k gyms and health clubs and pay an annual, monthly, or daily fee to work out. Collectively, gyms rake in $30B+ in revenue on an annual basis..

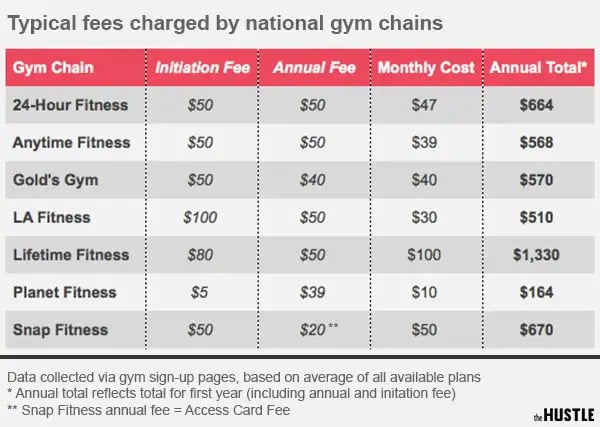

Membership fees vary widely based on your location and gym of preference, but the industry-wide average falls in at $58 per month, or $696 per year.

On top of the monthly fee, gyms often tack on an “annual fee” (paid at the start of each new membership cycle), and an “initiation fee” (a one-time dinger that can run as high as $250, due upon signing).

The main purpose of these fees is to give the gym something to reduce to make you feel like you’re getting a “special” deal. In reality, the gym’s out-of-pocket costs to sign you up ring in at a measly $3.

Generally, most of these fees are pretty fair.

If the average gym-goer were to use a gym 7 times a week, every week, without fail, $696 per year would work out to a measly ~$1.90 per visit. Even at 4 times per week, you’d be looking at $3.36 per visit.

But here’s the thing: We don’t even come close to 7 gym visits per week. Or 4. Or even 3. What makes a gym membership a poor investment is your lack of commitment.

Staying home and eating cake counts as leg day, right?

A study run by a pair of UC Berkeley economists found that while members anticipate visiting a gym 9.5 times per month, they only end up going 4.17 times per month. That works out to 50 visits per year.

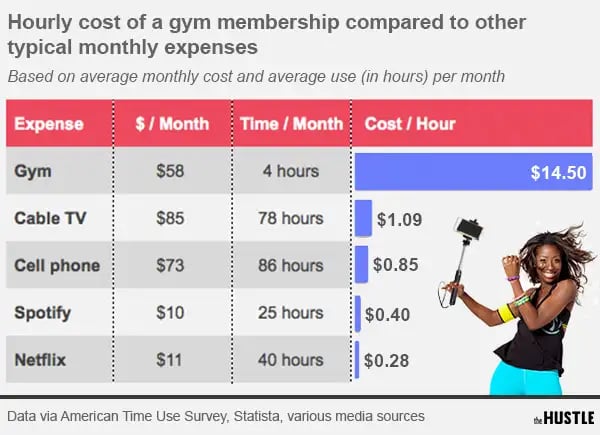

Assuming an average session length of 1 hour, the typical gym member is suddenly paying $14.50 per workout. This stacks up pretty poorly with other things we pay a monthly fee for:

Why on Earth is this average so low? Well, it turns out that a vast swath of people who pay for gym use just… don’t go at all.

A Statistic Brain survey [paywall] of 5,313 American gym members found that 63% of memberships go completely unused. The granular stats are even more dismal:

- 82% of gym members go to the gym less than 1 time per week

- 22% completely stop going 6 months into their membership

- 31% say they never would’ve paid had they known how little they’d use it

From their data, the survey authors estimate that the average gym member “underutilizes” two-thirds of her gym dues — roughly $39 per month, or $468 per year.

And as it just so happens, our laziness and lack of commitment are the lifeblood of big-name gyms’ business model.

Gyms bank on you NOT showing up

Each January, when our ambition is riding higher than a SpongeBob wedgie, gyms experience a 50% uptick in memberships.

It’s what one fitness director once called “the perfect storm” — a time when “cold weather [and] a psychological awareness about achieving goals” draw out lofty ambitions. But most of these new signees, like our pal Josh Kline, eventually fall off the proverbial treadmill.

It seems counter-intuitive, but big-name gyms don’t want us to work out.

“If gyms operate at more than 5% of their membership at any given time, no one can use the gym,” explains one branding consultant. “They want [people] to sign up, but they know that after the 15th of January they won’t see 95% of them again.”

The nation’s largest gym chains often sign up 20x the number of people who can actually fit in a given location. They are well aware that most won’t show up.

As Planet Money reported, one Planet Fitness branch in NYC had a max capacity of about 300, but boasted more than 6k members. Similarly, Gold’s Gym and Life Time Fitness often ink 5k-10k memberships per location despite having only being able to house 300-500 people at a time.

In essence, the people who don’t show up “subsidize” membership costs for those who actually do go, allowing gyms to keep their prices down.

So, why do we keep signing up?

As the late economist Thomas Schelling laid out in his 1978 paper, Egonomics, we have “two selves:” The present self (who is highly motivated to work out come January 1st), and the future self (who will inevitably quit by March). These selves are engaged in a “constant conflict between immediate desire and long-term goals.”

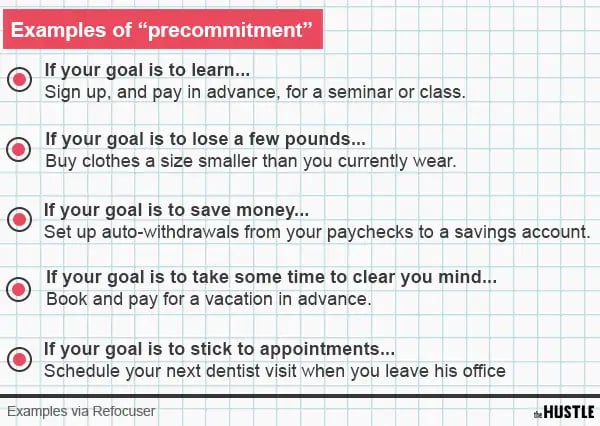

Oftentimes, the present self will trick the future self into making good decisions by enlisting a little concept known as “precommitment:” We commit to something in advance to make it harder — or impossible — for our future self to back out.

If our goal is to save money, we might set up automatic paycheck deductions into savings. If we want to learn a new language, we might pay for classes in advance. And if we want to exercise more, we might lock ourselves into annual gym memberships.

As the blog Refocuser writes, by precommitting, you must “always assume your future self is lazy… you’re practically dragging your future self kicking and screaming toward the ‘right thing’ by taking away his or her alternative options.”

Thing is, this just doesn’t work — and it ends up costing most people money in the long-term.

Okay, so how do I work out for cheaper?

You shouldn’t blame any of this on gyms: They promote fitness and well-being, and, in general, are priced pretty reasonably considering mechanical upkeep, equipment costs, and employee overhead.

Still, it’s hard to justify the cost when the odds of regular attendance are stacked so unfavorably against you.

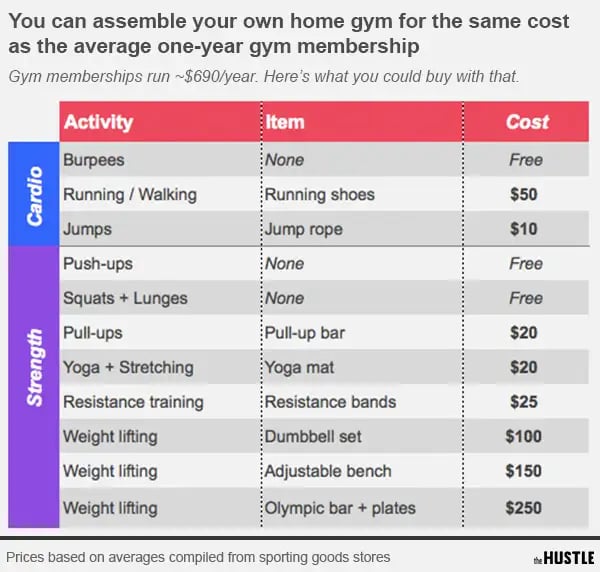

One alternative is to simply build your own home gym.

The Department of Health and Human Services recommends 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity (or 75 minutes of “vigorous” aerobic activity), in addition to at least 2 sessions of major muscle group strength training, per week. This is easily achievable without a gym membership.

While the equipment you choose to buy depends on a number of factors, including what types of exercises you want to do, and the space you’re working with, it’s possible to build a relatively space-efficient, full-body setup for the same cost as one year at a gym.

Let’s say you pay the average monthly gym fee of $58 ($696 per year). A home gym, at ~$625, will pay itself off in a little under 11 months; after that, you’re saving $58 per month in perpetuity.

Over the course of, say, 5 years, that amounts to $3,480 in savings — enough to hire a drill sergeant to berate you into working out every day. Problem solved!