On New Year’s Eve, Monopoly celebrates the 85th anniversary of its patent.

Its publisher, Hasbro, can toast the occasion knowing that its prized board game is more popular than ever.

In 2013, Euromonitor pegged Monopoly’s annual revenues at ~$400m. By one estimate, that accounts for ~30% of all mass-market board game sales in the world — equivalent to Google’s share of the US ad market.

The pandemic has created another boom: Gaming sales for Hasbro reached a record high in Q3 of 2020. In the UK this spring, board game and jigsaw puzzle revenues were up 240% — and Monopoly was the top seller.

Ask industry observers and fans why Monopoly has thrived, and they point to the game’s unique storyline, nostalgia, and a desire to escape screens.

But there’s another factor at play: Hasbro created a real-life monopoly that allowed Monopoly to flourish.

How did Hasbro corner the board game market? And could a new wave of collaborative board games threaten to disrupt their dominance?

From family business to consolidation

Board games as we know them came into existence around the middle of the 19th century. Many were inspired by religion and designed to imbue children with values of honesty, gratitude, and fair play.

In the wake of the Civil War, industrialization, and Christianity’s embrace of the prosperity gospel, the overriding theme of board games shifted from morality to unbridled capitalism.

And no game captured the spirit of Carnegie and Rockefeller like Monopoly.

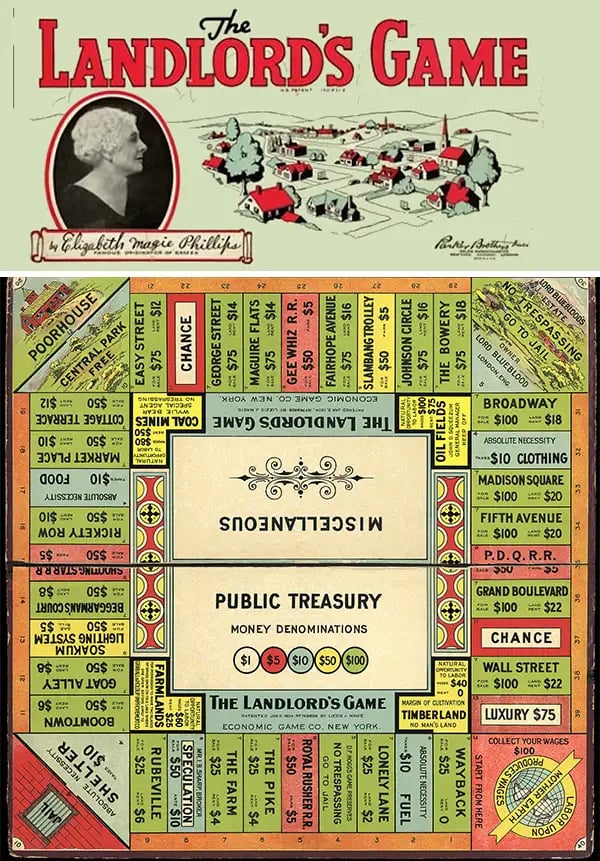

The Landlord’s Game — the precursor to today’s Monopoly (LandlordsGame.Info)

Monopoly began its life as The Landlord’s Game.

As Mary Pilon writes in the book The Monopolists, the game was patented in 1904 (and again in 1924) by Lizzie Magie, who originally intended to illustrate the injustices that can arise from the mass accumulation of wealth by one person.

The Landlord’s Game, which Magie self-published, became a cult classic. And eventually, it drew the attention of a man named Charles Darrow.

Darrow distributed his own version of the game — called Monopoly — and, despite not being the original creator, licensed it to a large-scale family business called Parker Brothers.

In November of 1935, Parker Brothers bought the invention patent for The Landlord’s Game from Magie for $500, then credited Darrow as Monopoly’s sole inventor in ads for the game.

Magie felt she had been hoodwinked and told her story to the press.

But there was no going back: Parker Brothers would soon use its Monopoly patent to stifle competitors.

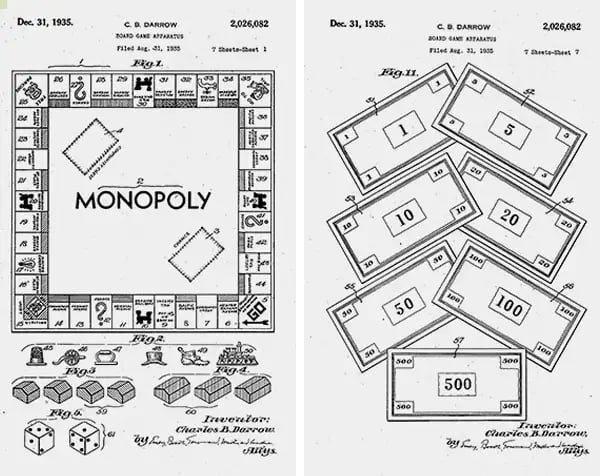

Images from Parker Brothers’ 1935 patent (Google Patents)

Monopoly violated the cardinal tenets of board game design: The rules were confusing and a single game took an eternity to finish.

Players didn’t seem to mind: In 1936, Parker Brothers sold 1.8m copies at $2 each (~$37 in 2020 dollars). And for the next 30 years, the company averaged ~1m copies in annual sales.

Before Monopoly came along, Parker Brothers had flirted with bankruptcy. This influx of sales single-handedly kept the company in competition with rivals like Milton Bradley and Transogram.

“Having a hit in the board game or toy industry is so rare — and having one multigenerational game was pretty much unheard of,” Pilon tells The Hustle. “Monopoly proved board games could be very lucrative. It really upped the stakes.”

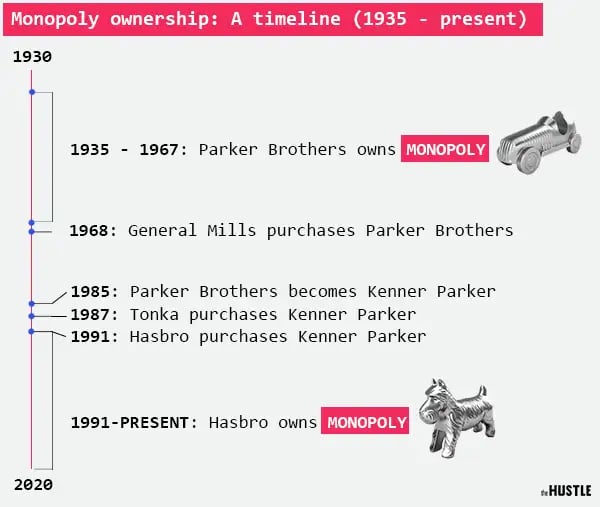

But a toy company called Hasbro — best known for making Mr. Potato Head — would end up on top.

Founded by the Hassenfeld brothers in 1923, Hasbro became a player in board games in the early 1980s when it acquired Milton Bradley. The company went on to buy other board game companies like Avalon Hill, Wizards of the Coast, and Coleco.

In 1991, it wrangled Parker Brothers away from Tonka.

Though the acquisition raised antitrust concerns, the FTC never took action. And just like that, a once wide-open industry was largely closed to competition.

The Hustle

Philip Orbanes, who worked for Parker Brothers and Hasbro and has written multiple books about Monopoly, estimates that by the late ’90s Hasbro had cornered 85% of the board game market.

Twister? That belonged to Hasbro. The Game of Life? Hasbro. Battleship, Candyland, Scrabble, Risk, Clue, Magic: The Gathering, Dungeons & Dragons, Ouija — all Hasbro.

There was an easy word to describe the newfound dominance: It was a monopoly.

From new games to brand extensions

Having vanquished the competition, Hasbro acted like the industry behemoth it was:

- It engaged in price fixing with distributors: In 2002, the company was issued a then-record £4.9m (~$8m) fine by Britain’s Office of Fair Trading.

- It slashed jobs: Despite Hasbro’s expansion, employment declined from 13k in 1995 to 10k in 1998, according to the company’s annual disclosures. (The company now has 5.8k employees.)

But most notably, it stopped developing new games.

Rob Daviau, who worked at Hasbro from 1998 to 2012 and is now an independent designer, recalls new titles becoming rarer and rarer as Hasbro prioritized an ethos that had served its toy business well: building on existing brands.

It was an easy calculation. Extending a brand was far less costly than developing a new game. And Monopoly, Daviau says, “was the flagship brand.”

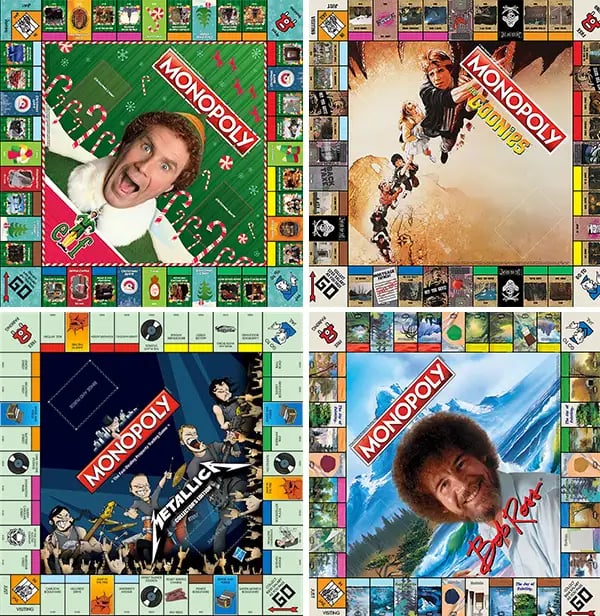

From 1995 to 2005, some 230 official affinity versions of Monopoly were produced. In 1997, Hasbro made a Star Wars Monopoly under license from LucasArts, a formula it went on to replicate with Marvel, Disney, and other entertainment companies.

“It felt like utility stocks,” Daviau says. “They were going to go out and make money, and they weren’t incredibly difficult to make as a designer… It was a good way to make sure the brand was making the numbers.”

Weird versions of Monopoly include Elf, Goonies, Metallica, and Bob Ross themed boards; other honorable mentions: Alaska Iditarod Monopoly, Pedigree Dog Lovers Monopoly, Monopoly Socialism, and Berkshire Hathaway Monopoly (Hasbro)

As recently as 2011, industry analysts warned that Hasbro’s emphasis on reinventing classics rather than creating new games was doomed to fail.

But largely thanks to Monopoly, the company has experienced double-digit growth in board game revenue. In Q4 of 2018, a down year at Hasbro, 2 games — Monopoly and Magic: The Gathering — net ~$212m in sales alone; all other games totaled ~$267m.

“We used to boast at Parker Brothers we had sold 80m Monopoly games around 1990,” Orbanes says. “The number today is probably approaching or over 300m.”

Monopoly’s new climb in popularity has coincided with an emphasis on cultivating IP in nearly every entertainment sector. The sequels and spinoffs that involve less risk and less cost are attractive to consumers, who want to repeatedly experience the same entertainment properties.

The average shopper may also have trouble realizing that anything besides classic board games are available:

- Hasbro Gaming’s website features 240 board games, the vast majority of which were invented decades ago; 45 of the games are variations of Monopoly.

- Amazon’s “Monopoly Games & Accessories” category returns 676+ results, from the classic version to titles you would never believe exist, like Monopoly Socialism.

Under Parker Brothers, Orbanes says, executives feared saturating its prized possession. These days you can play infinite versions of the Monopoly board game, the computer game, and the iPhone game (which is so popular it has more App Store reviews than Tinder).

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Hasbro has so far proved there is no limit for brand extension.

“If not for that attitude, that confidence, that expertise, and that investment in expansion, Monopoly would be in terms of overall sales probably a fraction of what it is,” Orbanes says. “That’s where Hasbro clout has made a difference.”

A newcomer: The rise of Asmodee and hobby games

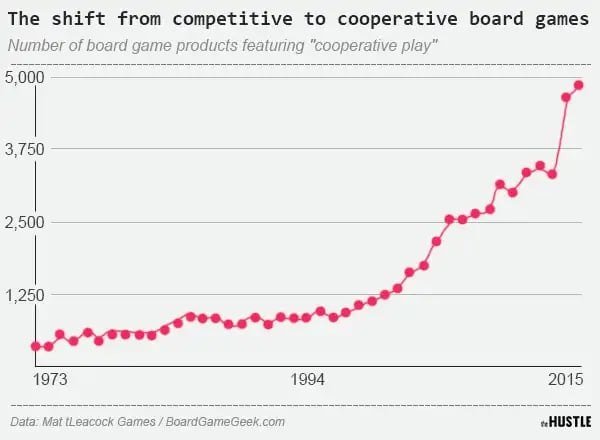

While Hasbro nurtured Monopoly and other classics, independent German publishers started to produce board games with more complex strategies and sleeker designs — games that were about cooperation as much as competition.

One of these games, Settlers of Catan (now known as Catan), turned into a breakaway hit. Between 1995 and 2010, it sold ~15m copies globally.

Ticket to Ride, released in 2004, became another phenomenon and showed Catan wasn’t a fluke. Trend pieces abounded about the rise of a new style of game that would replace Monopoly and similar pop-strategy games, which have been derided as Ameritrash.

Hasbro took a pass on games like this — and that opened the door for smaller companies like Mayfair Games, Days of Wonder, and Plaid Hat.

These companies comprised the hobby section of the board game market, and its heavy fragmentation resembled the pre-consolidation days of the mass market.

Then, along came a French company called Asmodee.

Or, as some board game fanatics like to call it, the “Borg” — because it is taking over by assimilation.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Launched in the 1990s, Asmodee was an afterthought until 2014 when the private equity firm Eurazeo purchased a majority stake in the company and began to rapidly expand.

Asmodee went on a buying spree reminiscent of late 20th century Hasbro.

From 2014 to 2018, it made 20 acquisitions, purchasing Mayfair Games, Fantasy Flight Games, Days of Wonder, and N2Z. The biggest hobby market titles, from Catan to Ticket to Ride to Arkham, now belong to Asmodee.

The company’s revenues leaped from €125m in 2014 to €442m in 2017 — almost half of Hasbro’s 2017 gaming haul. And Eurazeo cleaned up: It purchased Asmodee for €143m and sold it in 2018 to another private equity firm, PAI Partners, for €1.2B.

After the sale, PAI announced its plan for Asmodee: further expansion through acquisition.

The year 2020 has seen Asmodee make its fair share of monopoly moves.

In March, it hiked the MSRP of many of its signature games by $5 to $10. It also announced it was launching its own US distribution unit.

The company had already bought numerous European distributors, to the extent that Stephen Conway, president of a board game nonprofit called The Spiel Foundation and a longtime industry observer, says Asmodee effectively controls European board game distribution.

Asmodee is creating its own monopoly with games like Catan, pictured here (Britta Pedersen/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Some believe the company will elevate hobby games to greater mainstream status and bring more consistency to the market.

Others foresee Asmodee focusing too heavily on its most popular games — like Habsro with Monopoly — while blocking the path to mainstream success for new titles.

Either way, attaining Hasbro levels of power appears to be the goal.

End of the Monopoly?

When you own the equivalent of Boardwalk and Park Place and somehow a challenger — whose best piece just a few years ago was Baltic Avenue — cuts into your lead, how do you react?

Hasbro representatives did not respond to The Hustle’s request for an interview. But given the history of the industry and the convergence of mass market and hobby games, insiders have hypothesized that one player will try to take over the entire board.

According to Conway, “As the larger investment firms become involved (with Asmodee), you could see them saying, ‘Why not set our sights on somebody like Hasbro?’

“Then again Hasbro might look at the up-and-comer and flip the script on them and say, ‘Let’s buy out the competition.’”

Some of Hasbro’s recent actions indicate it may be taking the hobby game market and Asmodee more seriously. In September, it moved Avalon Hill, a subsidiary and producer of niche games, to direct supervision by Hasbro’s gaming unit.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Unlike board game-focused Asmodee, Hasbro has also invested in growth beyond toys and games.

It bought Entertainment One, which made Hasbro the parent of DreamWorks, Amblin Entertainment, and, among other things, Death Row Records (there is no word on whether a Suge Knight Monopoly game piece is forthcoming).

In 2017, Hasbro flirted with a purchase of the movie studio Lionsgate, and last year announced, with Lionsgate, the production of a Monopoly movie. Kevin Hart is slated to star.

So just as Asmodee games capture unprecedented attention, Hasbro is making its prized asset even more ubiquitous.

It’s never easy to take down a monopoly, much less one that owns Monopoly.