The Sharper Image was a kingdom.

It was a kingdom where you could, in an afternoon trip to the mall, purchase an electric nose trimmer ($39), a motorized surfboard ($2,450), and a bulletproof raincoat ($400), then take a ride in a $1,500 massage chair while being serenaded by a bird-calling robot.

It was a kingdom once described as the “breast implant” of retail, a place where man and child alike could bask in the artificial glow of flagrant consumerism.

This is the story of the man who founded this great kingdom — and how one flashy gadget ultimately led to its downfall.

King Richard I

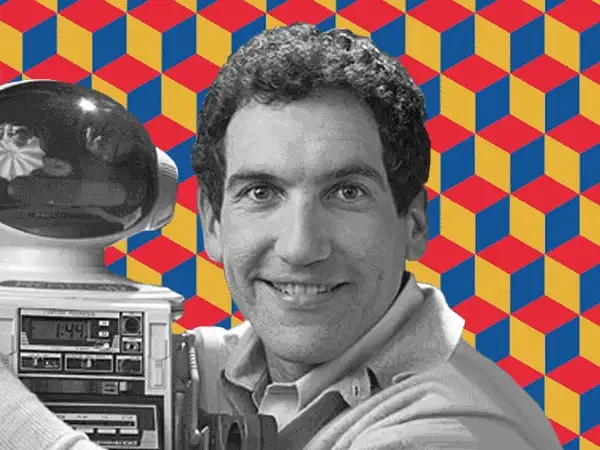

Richard Thalheimer had all the trappings of a world-class salesman.

Born in 1948 in Little Rock, Arkansas, he spent his youth working odd-jobs in the toy section of his father’s department store. He went on to study psychology and sociology at Yale University, where — during his freshman year — he sold enough encyclopædias to buy a brand new Porsche.

In his early 20s, Thalheimer ventured to San Francisco and started a wholesale business that catered to the then-burgeoning photocopier industry.

“I named it The Sharper Image,” he says, “because I thought that my paper and toner would help people make good copies.”

While running The Sharper Image, Thalheimer enrolled at Hastings Law School — but making physical deliveries to businesses in the Financial District every afternoon between classes began to take its toll.

“I was completely taxed,” he says. “So I thought, ‘Why don’t I try mail-order?”

The million-dollar running watch

The mail-order catalog — a publication that lists products and allows customers to order them remotely via mail or telephone — had been around for a century. As early as the 1880s, Tiffany’s and Sears were hawking their wares in 300-page booklets.

But in the 1970s, the mail-order industry was having a renaissance moment: Roger Horchow had just launched the first luxury color catalog without a physical retail location, and Joe Sugarman was running the first-ever mail-order magazine ads — beautiful, full-page photos with poetic product descriptions.

Thalheimer wanted to try his hand at it. But first, he needed a product.

At the time, Seiko had just rolled out a first-of-its-kind fully digital watch — but at $300, most runners couldn’t afford it. Coincidentally, Thalheimer came across a small booth at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, where a man was selling a “very similar” product for $35 wholesale.

He struck a deal with the vendor and bought out a full-page ad in Runner’s World Magazine, offering the watch for $69. For the copy, he chose to feature his friend, Walt Stack — a “legendary, fully-tattooed 70-year-old” who was known around San Francisco for his crazy daily routine, which included a 17-mile run across the Golden Gate Bridge.

At a cost of $1k, the ad netted Thalheimer $10k in sales (about $5k of which was profit). He repeated this process — each time, with better results — and by the age of 27, he’d made his first million dollars.

By 1979, Thalheimer’s system of advertising was so successful that he decided to launch his own catalog of high-tech gadgets nobody knew they needed.

The Sharper Image catalog

Thalheimer embarked on a quest to find the most unique products on the market — things that “other people didn’t sell.”

“At the Consumer Electronics Show, everyone would gravitate toward the big guys, Sony, Panasonic,” he says. “I’d go straight for the little booths, the people selling things nobody had ever heard of.”

The first catalog contained 25 items, including the first cordless phone, answering machine, and car radar detector. He avoided superfluous adjectives in his copy and focused on the features that made the products exceptional.

Very quickly, his experiment began minting money: The first year, sales topped $500k; the second year, they reached $3m; by 1980, $12m. Soon, the catalog was being sent to 3m people around the world, at a cost of $1.4m per mailing.

He catered specifically to the 20% of Americans who had credit cards and offered them a 1-800 number to place orders over the phone. In a small San Francisco office, with a staff of 5 or 6 people, a dozen orders were processed every 60 seconds.

The Sharper Image struck at the right time.

In the 1980s stock boom, flashy gadgets and conspicuous consumption were in. “He who dies with the most toys wins” was the ethos of the decade.

Thalheimer expanded into physical retail, opening stores in well-to-do enclaves across America. In New York, bankers dipped in to peruse $1500 massage chairs; in Hawaii, tourists fawned over electric nose hair trimmers and talking scales. By 1985, The Sharper Image was grossing $100m in sales — with no outside capital or debt.

At the company’s helm, Thalheimer was what the New Yorker described as the “very model of a major entrepreneur:” Tanned and muscular, deliberate and tenacious, and infallibly gifted at curating ridiculously niche gadgets, like a mini electric fan on a necklace (priced at $49, it sold 10k units a month).

“I can see the future,” he told an LA Times reporter in 1984, “I know when a trend is coming and when it’s leaving.” In an AP interview, he hailed himself as a “marketing genius.” Nobody could disagree.

When The Sharper Image IPO’d at $10 per share in 1987, the chain, and its outspoken CEO, seemed incapable of failure.

That is, until the ‘80s ended.

Do I really need that gadget?

In the early ‘90s, the economy weakened and sparked a recession: Suddenly, conspicuous consumption was out and frugal environmentalism was in.

The Sharper Image tried to switch gears by selling more “socially responsible” products (like Birkenstocks, vitamin energizers, and benches made of recycled plastic), but the strategy had a limited effect.

Between 1989 and 1991, sales fell by 28%. Staff was cut by 20%. Stock tumbled to $2. And for the first time in company history, The Sharper Image posted a loss.

“The Sharper Image has become a cliche for the worst excesses of the last decade — the Donald Trump of specialty retailing,” wrote the SF Examiner. “Nobody needs what they sell.”

For a CEO of a publicly-traded company, Thalheimer was unusually involved in minute decisions: His penchant for controlling what color clothes employees could wear, how they decorated their desks, and what type of coffee mugs they used earned him a citation in California Magazine’s 1988 Worst Bosses in America list.

So, he decided to step back from day-to-day operations and go back to his roots: Finding wacky, one-of-a-kind products. It didn’t take long.

At a “hippie street fair” in San Francisco, Thalheimer stumbled across a blue gel shoe insert — the first of its kind. “I stood up in front of all my deflated employees, pulled this thing out of my suit pocket, and said, ‘This is going to turn us around,’” he recalls. “Everyone thought I was nuts.”

At $19.99 a pair, the inserts went on to become the company’s best-selling product, selling thousands of units a day and adding 50% to their sales figures.

Several years later, in 2000, Thalheimer came across another game-changing product at a toy fair in Hong Kong: The Razor scooter. He negotiated an exclusive 24-month deal and sold a million of them in the first year. It was, he says, “a second lease on life” for the company.

Bolstered by the rise of the internet and online sales, the Razor led The Sharper Image to the best performance in its 23-year history. It was no longer just a place for “tech-loving snobs” to buy elitist gadgets.

But this success came with a looming concern: The Sharper Image was turning into what analysts described as “a one-product company.”

The air purifier that killed the company

Thalheimer had long operated by finding intriguing products elsewhere, signing exclusive distribution deals, and selling them under The Sharper Image brand name. But he knew that if it designed and patented his own products, margins could be higher.

In a secret location north of San Francisco, Thalheimer assembled a team of engineers and designers and formed Sharper Image Design to make gadgets in-house.

“[It was a place] where the inner child could come out in every man, with gizmos blinking and whirling,” later recalled an employee. “The only thing missing were white coats and propeller hats.”

The team churned out some 300 patents and 100 products, ranging from fogless mirrors to anti-snoring wristbands that jolted the offender with an electric shock.

But the crown jewel of the operation was a noiseless air purifier called the Ionic Breeze.

The Sharper Image put all of its resources behind the machine, taking out hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of magazine, newspaper, and TV ads. Despite its $229 price tag, it became a smash hit.

By the turn of the millennium, the Ionic Breeze was so popular that it made up 45% of all of the chain’s sales. And as it turned out, this was a huge problem.

In 2002, Consumer Reports (a nonprofit product review publication) ranked the Ionic Breeze dead last in a feature on air purifiers, deeming it “ineffective.” Thalheimer was furious, and filed a lawsuit against the magazine, claiming it had “negligently disparag[ed] the product.” It was tossed out and cost Thalheimer $525k in legal fees.

“We did a very stupid thing by making a big stink out of it,” cedes Thalheimer. “It was like suing Jesus Christ…it infuriated them, and just led to more trouble.”

Three years later, Consumer Reports struck again — this time alleging that the Ionic Breeze didn’t just suck at purifying air, but actually emitted harmful amounts of ozone. Once again, Thalheimer took them to court and lost.

The blowback cost The Sharper Image millions of dollars in-store credits and refunds — and soon, stockholders began to question Thalheimer’s magic touch.

Held at Knightspoint

In the Spring of 2006, a group of outside shareholders by the name of Knightspoint Partners snapped up 13% of the company.

Led by famed corporate raider Jerry Levin, the group demanded a shakeup of the board. At first, it seemed they genuinely wanted to help Thalheimer guide The Sharper Image back on track, but it soon became clear that they were gunning to oust him and remodel the company in their own image.

In September, Thalheimer was fired and forced to sell all of his remaining shares for a sum of $26m — a fraction of what his holdings were once worth. When he came into work the next day to gather his belongings, the door was locked. His desk, still covered with the wacky emblems of his career, was now occupied by Jerry Levin.

Knightspoint set to work recrafting The Sharper Image into a general electronic retailer, like Circuit City or Best Buy. Or, in Thalheimer’s estimation, “stripping away the imagination.”

By 2008, stock had plummeted to 28 cents per share. Within a year, The Sharper Declared bankruptcy, closed down all 183 stores, and laid off 4k employees.

The company, now run by an investor group, continues to exist online — but it’s a shadow of its former self. The weird gadgets have been usurped by USB drives and motion-activated light bulbs — and Thalheimer’s oddball charm is nowhere to be seen.

Richard Solo

Looking back, Thalheimer doesn’t harbor much ill-will. He runs his own gadget site, aptly named RichardSolo.com, and has taken up investing.

“My days are a lot more enjoyable,” he says. “It’s not as egocentric as being the head of my own company. But at this point, I’d rather be alone.”

He tells The Hustle that his net worth is “3-4x higher” than when he got pushed out, and that his studies of the stock market have earned him beefy returns of between 50% and 100% per year.

But Thalheimer hasn’t completely abandoned the kingdom.

At his Marin County mansion stands a lavishly-adorned suit of armor — a $2,450 relic from The Sharper Image catalog. An old cordless telephone dangles from its ear.

It is a sight that can only be described as perfectly Thalheimerian: A blend of the old and the new, the eclectic and the cutting-edge, the blunt and the sharp.