For 22 years, Zachary Moore sat in a 6×9 foot prison cell. Today, he sits in an open-plan office in San Francisco, surveying code.

At 15, he was sentenced to life for murder. Now 38, he has a full-time job as a software engineer, working alongside Stanford-educated colleagues. His six-figure salary places him in the 85th percentile of American workers.

Moore’s story is one of perseverance, hard work, and redemption — but it raises a controversial question: Should a convicted killer be given a second chance?

A terrible crime

Moore grew up middle-class in a quiet neighborhood in Redlands, California.

He led the typical life of a suburban Inland Empire kid — video games, sports, hanging out with friends. But at home, life was wildly dysfunctional.

His parents, both alcoholics, went on frequent drinking binges, sometimes leaving their children without food. Domestic abuse was common, and sharing feelings was discouraged. As Moore entered his teenage years, he had trouble managing his emotions and self-medicated with alcohol and drugs.

“I was ignoring the problems in my life, numbing them,” Moore told The Hustle in a series of recent interviews. “Alcohol and drugs made my emotions more extreme… and everything compounded.”

On the night of November 8, 1996, a distressing argument with family members pushed Moore over the edge. As years of “misplaced anger, jealousy, and pain” rushed through his mind, he made a choice that would upend his life.

Shortly after 11:30pm, he picked up a knife, approached the couch where his younger brother slept, and stabbed his sibling to death.

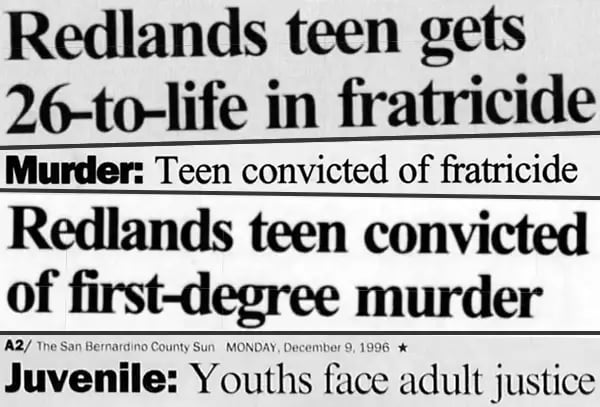

At trial, Moore’s defense attorney placed blame on an environment rife with drug use, alcoholism, and domestic abuse. The crime, he posited, was some kind of psychotic break — a reaction to years of neglect. The jury didn’t take pity.

Under a then-newly passed California law, Moore was tried as an adult; in September of 1997, he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to 26 years to life.

“The juvenile system is geared toward rehabilitation,” a prosecutor on the case later told the San Bernardino County Sun. “It would appear highly unlikely that could happen due to the nature of this offense.”

Three days before his 17th birthday, Moore was shipped from juvenile hall to a high-security prison.

Self-discovery in a cell

For the next few years, Moore bounced around from prison to prison, grappling with who he was and what he’d done.

“Prison was like high school — it was a bunch of 30-, 40-, 50-year-old men who were emotionally trapped as teenagers,” he says. “People would wear these masks… they wanted to fit in and feel accepted. Nobody wanted to confront who they were.”

Moore got into frequent bouts of trouble and, in 2000, landed in Ad-Seg, a “cell within a cell” where he was on lockdown 23 hours a day with little human contact. For the first time, he says, he began to “pull away the layers.”

His crime had been the result of “extreme emotions” without an outlet. But ultimately, Moore came to accept that the circumstances he grew up with were not what killed his brother.

“Millions of kids in the world grow up like me and find other ways to work through things,” he says. “The reality was that I was the difference in that situation. There were things about me that I needed to address and fix.”

Moore soon gravitated toward a group of men in his prison who were trying to better themselves. Though frequently bullied and ridiculed by others in the cell block, they formed a “brotherhood” of support. He attended Buddhist services, meditation classes, and gradually, with the emotional support of fellow inmates, learned to “cut through the chatter of [his] mind.”

In his late 20s, Moore landed at Ironwood, a medium-security facility in Riverside County.

While there, he enrolled in an online college program at Palo Verde College, earned a pair of associate’s degrees, and graduated with a 3.89 GPA.

Then, one day, he saw a flier in a prison hallway for a program called The Last Mile.

Coding, sans internet

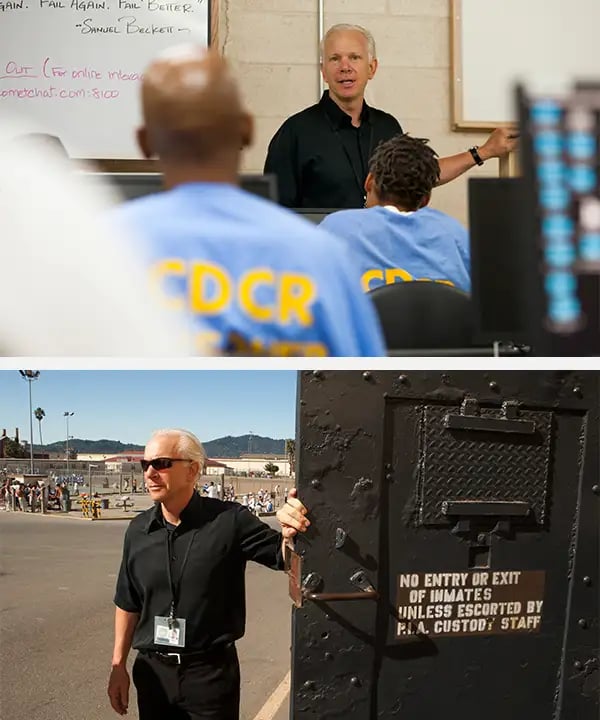

In 2010, serial entrepreneur and Silicon Valley investor Chris Redlitz was invited to give a business talk to inmates at San Quentin State Prison, just north of San Francisco.

“I expected to go there and find a bunch of bad people,” he says. “I quickly realized that many of these guys were skilled entrepreneurs who just had no avenue to learn and express themselves.”

With his wife, Beverly, Redlitz founded The Last Mile (TLM) and began offering a bi-weekly entrepreneurship program at the prison. But soon, it became clear to the couple that a larger systemic problem needed to be addressed.

When the formerly incarcerated are released from prison, they are given anywhere from $10 to $200 in cash and sent on their way, often with no job or housing prospects, and few contacts in the outside world. In California, nearly 7 out of 10 released inmates recommit a crime within 3 years. This perpetual cycle contributes to a growing mass incarceration crisis that imposes an annual $182B fiscal burden.

Redlitz wanted to empower inmates with “hireable skills” they could use to find employment upon release. In California, no skill was more hireable than coding.

So, The Last Mile launched a full-scale coding program at San Quentin.

With funding from several large foundations, Redlitz converted an on-site printing factory into a technology center equipped with off-line computers. To get around the prison’s strict no-internet policy, the program built a “faux-internet” using video seminars.

When The Last Mile expanded its coding program to Ironwood State Prison in June of 2015, Moore was among the first in line to apply.

HTML, CSS, JavaScript — and a ticket out

At the time, Moore had only used a computer 3 times in his life — all prior to 1996 — and he’d never seen the internet. The year he was incarcerated, AOL and Geocities ruled the web. Yet, coding intrigued him.

“I knew nothing about technology, but I had to take a chance on it,” he tells The Hustle. “I felt it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Though he had a life sentence, Moore still held out hope that he’d be released one day. And when he did, he wanted to be prepared to find gainful employment.

But first Moore had to pass The Last Mile’s screening process.

An interested inmate must have a clean record, with no infractions committed in the 2 years prior to applying (cybercrimes are an automatic disqualifier). He must have a track record of seeking out self-improvement behind bars. And he has to pass a logic test that gauges his linear thinking and problem-solving skills.

Since the program is focused on successful reentry, it favors inmates with less than 3 years left on their sentences. But it also reserves a 10% admittance for “lifers” like Moore, who might, by a stroke of bureaucratic luck, get a second lease on life.

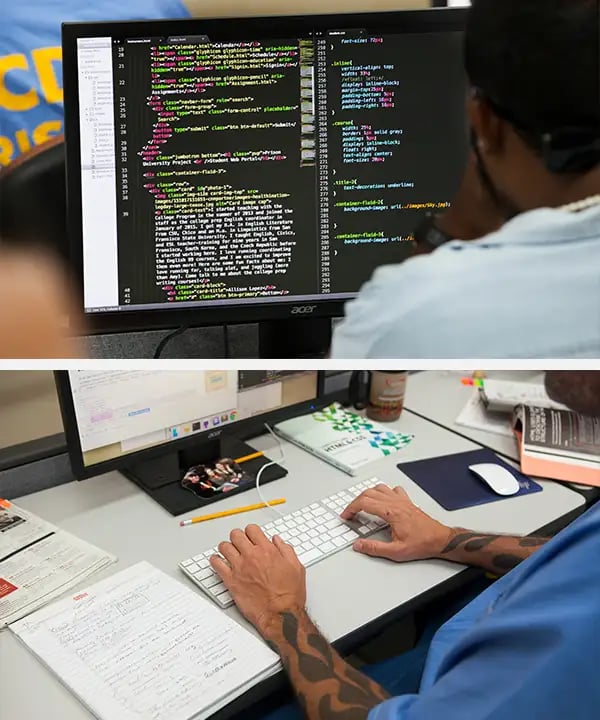

Moore was accepted and began the first of two 6-month curriculums.

Four times a week, from 7am to 2pm, he met with a small cohort to learn front-end code like HTML and CSS. For the first month, he was only permitted to write his code by hand; when computers were introduced, he relied on a combination of instructional videos (filmed remotely in a San Francisco studio by technical experts from the likes of Google, Airbnb, Slack, and Alibaba) and screenshots of real-life user flows.

“We had no internet access whatsoever,” Moore says. “It was mind-blowing learning this stuff because I had no idea what the free world actually looked like. It forced you to be intuitive and creative.”

The second 6-month chunk focused on back-end coding, incorporating Javascript and NodeJS. For his final “capstone” project, Moore built a mock e-commerce site from scratch: A marketplace of “nerd-related stuff” he called GeekChic.

Moore graduated among the top of his cohort and soon became aware that The Last Mile offered additional training at San Quentin, focused on advanced algorithms and data science. He put in for a transfer, was approved, and moved up north.

Not long after he arrived, he received some unexpected news: He had a chance at parole.

The road to Silicon Valley

In California, the laws around violent crimes committed by youth were being reexamined.

A state bill, passed in 2014, decreed that youth (under 18 of the time of the crime) who had been tried as adults were entitled to parole hearings to determine eligibility for early release. This was followed by another bill, which entirely banned courts from trying anyone under 16 as an adult.

In 2018, Moore was granted a hearing before the parole board.

He knew he’d changed as a person; now, he had to convince 12 people appointed by the governor of California.

“I walked them through my whole life, from age 3 to 37,” he says. “I laid myself before them… dissecting my entire thought process, and how I’d dealt with emotions.”

Moore’s parole was cleared, but the parole board still had 150 days to overturn the decision. For 5 months, he sat in wait, knowing that “at any moment, freedom could be taken away.”

In the meantime, he “threw [himself] into code,” completing the final tier of his course work. Through a program offered by The Last Mile, he even helped build elements of a live site for Dave’s Killer Bread, an organic bread company founded by an ex-convict.

On November 12, 2018, after 22 years behind bars, Moore walked free.

Representatives from The Last Mile picked him up outside of the prison, gave him clothes and a laptop, and set him up in a transitional house geared toward former lifers. Slowly, he began to reacquaint himself with society.

For 6 months, he worked part-time as an engineer for The Last Mile. Once he felt ready, he began applying for engineering internships at Silicon Valley tech companies.

“I knew there was no way in hell some of these companies would hire me,” he says. “I just wanted some practice interviews.”

According to Jennifer Ellis, The Last Mile’s chief operating officer, tech companies are often resistant to hiring the formerly incarcerated for two reasons: Legality concerns and cultural integration concerns. Both, she says, are understandable but unjustified.

“The formerly incarcerated have a red letter put on them for everyone to know they’re excluded from society,” she says. “But there’s a real opportunity for healing on so many levels, and tremendous value in opening up the workplace to people with different backgrounds.”

In a time of divisive politics, lawmakers across the aisle have agreed on policies aimed at “mainstreaming” former convicts back into society. Across the country, 25 states and 150 cities have passed legislation barring the inclusion of applicants’ criminal history on job applications.

The data show that the recidivism rate among the most violent offenders is especially low: In her 2012 book, Life After Murder, Nancy Mullane analyzed the cases of 988 released murderers in California over a 20-year period, finding that only 1% were arrested for new crimes. None were rearrested for recommitting murder.

But incarceration — particularly for violent crimes, and especially for murder — comes with longstanding stigmas that many hiring managers simply don’t want to deal with. The victim didn’t get to live a full and productive life, the reasoning often goes; why should his killer enjoy that privilege?

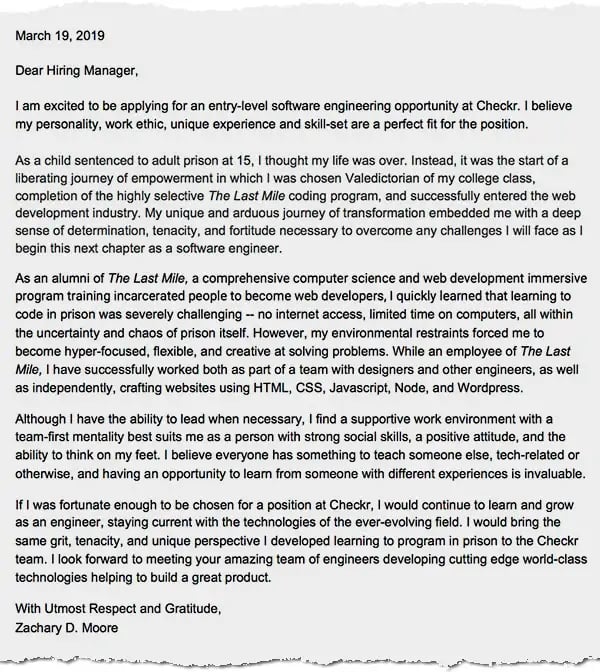

Moore broached these stigmas by being upfront about his past, which The Last Mile encourages. “I own my shit,“ he says. “I put my story in my cover letter and used it to explain what I’d learned about myself.”

In May 2019, Moore left his position with The Last Mile to become an engineering intern at Checkr, a background check technology firm that The New York Times has called one of Silicon Valley’s next “potential unicorns.”

In September, the company hired him as a full-time engineer — a role that comes with a “mid-six-figure” paycheck.

Checkr is one of a growing number of tech companies in Silicon Valley that has embraced the formerly incarcerated: 6% of its employees are “fair chance talent,” or people with prior criminal backgrounds.

“A conviction shouldn’t be a life sentence to unemployment,” a Checkr spokesperson told The Hustle. “If someone is motivated to make a change in their lives, their past shouldn’t define their future.”

The future

On a recent Saturday afternoon, Moore boards a commuter train in Oakland, where he currently lives, and heads toward San Francisco to meet up with another graduate of The Last Mile.

The two plan to do their regular “check-in” — talking through issues, hardships, and emotions — before watching Zombieland: Double Tap.

Since its inception, The Last Mile has transitioned 70 graduates into the workplace. Not a single one has returned to prison, the organization says.

It’s a small but important victory in the greater ecosystem of anti-recidivism efforts — and one that The Last Mile hopes to build on: The program now offers its coding courses at 15 men’s, women’s, and youth facilities spread across 5 states.

In some ways, Moore is an atypical graduate. As a middle-class white man, he says, he carries a “privilege that gives [him] an edge.” Mass incarceration disproportionately affects minorities, who face additional systemic barriers upon release. The seriousness of his crime also pushes the reform debate to its most extreme limits.

Though Moore has since reconnected with his parents, he doesn’t feel it’s his place to ask for forgiveness. He can’t imagine ever fully forgiving himself.

“I have incredible remorse that will never go away,” he says. “My brother will never have the life he was supposed to live. He’ll never be there for Christmas, Thanksgiving, or birthdays.”

But in the eyes of Chris Redlitz, of The Last Mile, it is these hardships that make Moore a desirable job candidate in a tech space that values resilience.

“There’s this idea in Silicon Valley that if you fail, you get up, dust yourself off, and try again,” says Redlitz. “Who embodies that better than a guy like Zach?”