The Shake Shack at 225 Varick Street in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, looks like any other fast-casual eatery: Inside, customers chow down on crinkle-cut fries, mill around the pick-up counter, and watch burgers sizzle in the kitchen.

But walk down a set of staircases, past the bathrooms and through two sets of doors, and you’ll find something different going on in the basement:

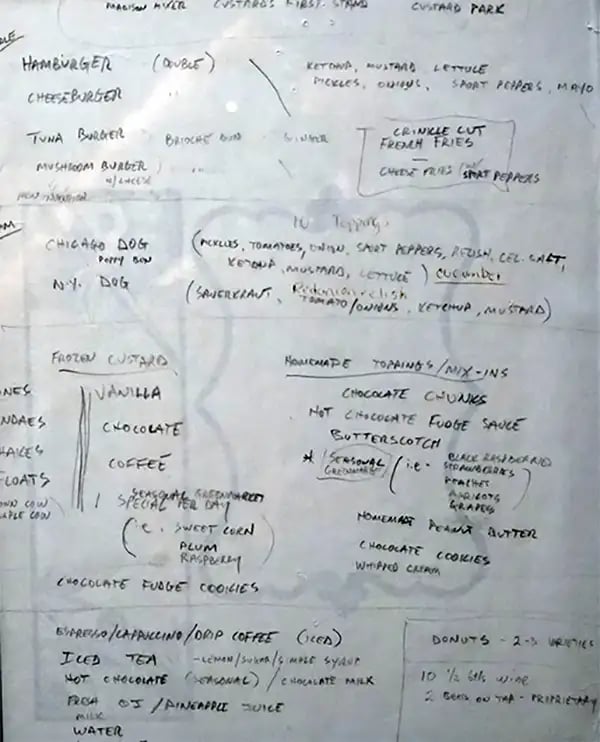

Here, in Shake Shack’s so-called Innovation Kitchen, a small team of chefs dreams up new menu items (like black sesame shakes and hot chicken sandwiches), with the goal of receiving “real-time feedback” from diners upstairs.

In a little more than a decade, Shake Shack has grown from a lone kiosk in New York City to one of America’s fastest-growing food chains, with nearly 250 locations all over the world and a projected 2019 revenue of $590m.

As it continues to grow, Shake Shack has chosen to adhere to an axiom many start-ups can relate to: “The bigger you get, the smaller you have to act.” Its new Innovation Kitchen is central to this effort, allowing the company to experiment with reckless abandon, iterate quickly, and let customers directly guide its menu.

So, what exactly goes on down there? And what can entrepreneurs glean from Shake Shack’s culinary ethos?

From hotdog cart to international chain

In 2001, a Michelin-Star-winning restaurateur named Danny Meyer, and his Director of Operations, Randy Garutti, opened a tiny hot dog stand in Madison Square Park, a then-run-down public space in the middle of Manhattan.

The stand ballooned in popularity and in July of 2004, Meyer transitioned it into a burger-slinging kiosk dubbed Shake Shack.

Meyer never intended to expand Shake Shack beyond this single kiosk, but the eatery’s financials were so impressive that he decided to give it a shot.

Flash forward 15 years, and the chain has 237 locations (157 domestic, 80 abroad). In 2018 alone, it built 49 new restaurants across 27 states and 13 countries. Since its IPO (2014), it has seen a 300% increase in sales — and its per-store revenue of $4.4m is now more than 2x that of McDonald’s, its much larger competitor.

But as the company continues to expand, it has become increasingly wary of losing touch with the very customers who’ve fueled its popularity.

Enter the Innovation Kitchen

Last year, in an effort to stay true to its roots, Shake Shake opened an underground food laboratory that allows the company to rapidly create, test, iterate, and roll out new items.

Headed by Shake Shack’s Culinary Director, Mark Rosati, the Innovation Kitchen was born out of a desire to “keep a small business mindset” in the face of corporate growth.

“One of the biggest things any company has to think about as it grows is how to stay nimble and able to push boundaries,” Rosati told The Hustle. “We ask ourselves: If we started [Shake Shack] today, what would we do differently?”

In the kitchen, a staff of 5 brainstorms and tests out menu items it plans to roll out regionally or nationally. The team might devote a week to formulating black sesame milkshakes for an opening in Japan, or “spend a whole day tasting cuts of bacon.” Every week, they test out these new creations in the restaurant directly upstairs.

Similar test kitchens have been implemented by larger chains, like Taco Bell, Chipotle, and McDonald’s, as a way to establish a more direct feedback loop with diners.

The Hustle recently visited Shake Shack’s Innovation Kitchen and chatted with Rosati about the chain’s philosophies on growth and product testing. Here’s what we learned.

1. It iterates fast and let the market guide its products

Many fast-food chains spend years on R&D and focus groups, and millions of dollars, before testing out a new menu item.

Shake Shack favors an approach more in line with iterative design. It moves quickly, sometimes bringing an item from the kitchen to customers in its NYC test restaurant in a matter of weeks.

Once an item is on the menu upstairs, it collects real-time feedback (through questionnaires, qualitative observation, and sales data) and uses it to fine-tune things. If the item performs exceptionally well, they may opt to release it in a few other restaurants around the US, in markets where they perceive it could hit.

From there, they assess whether or not the item has the potential to go national (this was the case with their Chicken Bites, which excelled at every stage).

“A lot of stuff will get to this part of the process,” said Rosati. “Sometimes we love an item, but just don’t know when to serve it, or where. So, we keep a big list of things we can roll out.”

A national roll-out, of course, requires a bit more time: It takes at least 3-4 months for Shake Shack to pass it by all the various departments, train its cooks, retrofit kitchens with the necessary equipment, and make sure ingredients can be sourced locally.

“There are risks when you bring customers into the testing process,” said Rosati, “but in the end, their feedback will always make the food better.”

2. It spares no expenses in learning about its customers

When Shake Shack decides to expand to a new city, Rosati will fly out and learn everything he can about what makes the region’s culinary palette unique.

“We’ll walk the streets of that city and try to find out what makes it tick, what makes the food different,” he said. “The R&D of flying people all over the world to find these things can be expensive — but it’s something we’re willing to invest in.”

Some examples:

- In Seattle, the supply chain team went on “two epic trips” all over northern Washington and toured 7 cattle ranches to find the right beef for its burgers.

- In St. Louis, they found a local cheesemaker and integrated Provel (a cheese unique to the region) into a burger.

- In Hong Kong, they sourced griddled ox tongue, Szechuan pepper, and Chinese bean sauce for a special burger.

- In México, they integrated traditional ingredients like mamey, horchata, and local chocolate into their menu.

When developing a new item, Shake Shack adheres to something of a “quality first, price later” philosophy.

As Shake Shack’s founder, Danny Meyer, told Reid Hoffman on the Masters of Scale podcast, the fast-food business has an unspoken rule: You can only choose two between quality, speed, and price — and most of the time, it’s speed and price. But fast-casual chains like Shake Shack strive to offer a lower-percentage mixture of all three.

“We try to create something that makes us happy first, and think about the price of those ingredients later,” said Rosati. “We might buy the most expensive, highest-quality ingredients out there try to make something with them. If we love a concept, we’ll figure out how we can scale it later.”

3. It doesn’t screw with what’s working

Of course, not everything should be tinkered with just for the sake of tinkering.

Back in 2013, Shake Shack learned this the hard way, when it decided to “upgrade” its crinkle-cut fries, the best-selling item on its menu.

The fries were the only frozen item the company sold and didn’t jive with its “everything is fresh” messaging. So, the culinary team decided to replace them with more premium hand-cut fries — a year-long process that came with a dramatic increase in labor, logistical, and equipment costs.

“We made these beautiful fries that we truly thought were better and rolled them out nationally,” said Rosati. “Right away, people were like, ‘Where the hell are my crinkle-cut fries?! You ruined my day!’”

A year into the new fries, the chain realized it had made a grave mistake and made the decision to revert back to the frozen crinkle-cuts.

“At the end of the day, there was a nostalgic value attached to those crinkle-cut fries that we just didn’t get,” said Rosati. “We had ‘come-to-Jesus’ moment, where we realized we had to really listen to our customers and loop them in more.”

Today, Rosati recognizes that it might be best to leave the chain’s “staples” (its crinkle-cut fries and ShackBurger) relatively untouched and save most of the innovation for new creations.