The name “Josiah Wedgwood” doesn’t pique the interest of most tech bros.

He didn’t grace stages clad in a black turtleneck. He didn’t build a steel or railroad empire. He wasn’t the richest man of all time, or the most powerful. But nearly 300 years ago, in a small village in the English hills, he revolutionized the way the world thought about business and entrepreneurship — by making pottery.

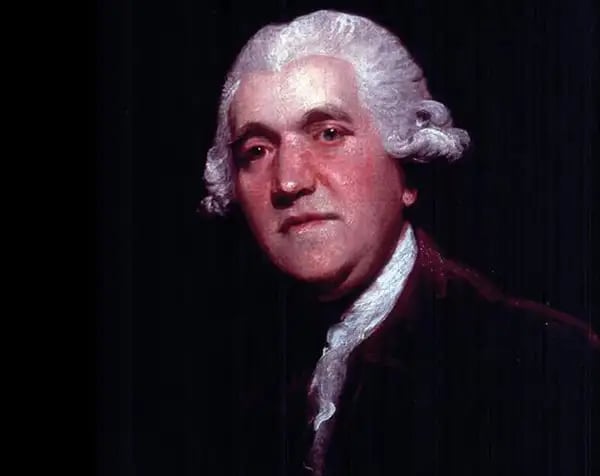

Wedgwood has been called the “first tycoon,” the “Steve Jobs” of the 18th century, and “one of the most innovative retailers the world has ever seen.” Scholars regard him as both the father of modern marketing and the creator of the first luxury brand.

In his quest to invent and sell ceramic wares, he pioneered sales techniques like money back guarantees, free delivery, and “influencer” marketing.

This is the story of a small-time potter from the middle of nowhere who turned a “rude uncultivated craft” into a thriving global industry.

A potter is born

Josiah was born on July 12, 1730, in Burslem, England, the 13th child of an impoverished and struggling potter.

In these times, pottery was seen as a crude, dirty, and “undignified” craft. Like most in the trade, Josiah’s father, Thomas, produced low-quality, cheap wares that were “black and mottled in color.” His work was a nothing more than a means of survival.

When Josiah was 9 years old, his father died, leaving the ailing business (and a mountain of debt) to his sons. The children worked brutal 12-hour days, lugging around and battering monstrous chunks of clay.

In these dismal conditions, Josiah contracted smallpox. He narrowly survived, but the illness left his right leg permanently crippled. Unable to perform manual labor, he began to experiment with the business side of pottery: Technology, marketing, and innovation.

By 22, he’d mastered the trade and decided to branch out on his own.

In a neighboring town, Josiah worked with Thomas Whieldon, a renowned potter who’d come up with a signature “tortoiseshell” glaze. By breaking from the mold, Whieldon had attracted acclaim and been able to boost his prices.

Here, Josiah came to his first entrepreneurial realization: “Invention without experiment signifies very little,” he wrote. “Everything derives from experiment[s].”

Move fast and break porcelain

At the time, however, there was little incentive to experiment: It was expensive and risky, and “entrepreneurship” was not celebrated like it is today.

But the young potter had been raised to “question the status quo” of establishments and “create [his] own culture.” And from his village in the hills, he began to notice a shift.

The act of drinking tea, and the fancy ceramic wares it required, was reserved for the upper class — but a “new consumer” was emerging, a generation of up-and-comers who wanted to “display their taste.”

Like aspirational Instagramers, these consumers wanted the world to see them as tea drinking socialites. They wanted fine tea decor, but porcelain was pricey and in short supply. There was a need, it seemed, for a cheaper, aesthetically-pleasing alternative.

Sensing this, Josiah returned to his hometown in 1759, opened a small shop, and voraciously experimented with new glazes and finishes. He picked up an interest in chemistry, studying the effects that “fire, clay, and minerals” had on color and texture. His workshop became a “graveyard of failed crafts.”

At last, Josiah’s experimentation paid off: He developed a cream-colored ware more “pure” than any before it — elegant like porcelain, but with the sturdiness and utility required for everyday use.

It wouldn’t be long before he established a lucrative marketing arrangement.

The first luxury name brand

In June of 1765, Josiah received a letter in the mail that would change his fate: An invitation to a competition.

It beckoned potters across the country to submit a “complete set of tea things” for the personal use of Queen Charlotte: Dozens of teacups, saucers, coffee mugs, candlesticks, sugar dishes, and fruit bowls.

Josiah understood something that other potters didn’t: Queen Charlotte was the ultimate influencer. As historian Brian Dolan writes, he saw an opportunity to do what “nobody else would undertake.”

He won. But more importantly, the Queen was so impressed with Josiah’s cream-colored wares that she decreed him “Her Majesty’s Potter.”

Recognizing new marketing value, Josiah placed ads in local papers advertising his pottery as “Queensware.” Suddenly, aspirational Britons were clamoring for his work.

At a time when no luxury brand names existed, he opened an exclusive showroom in London and built hype by capitalizing on consumers’ Queen-envy.

When people would walk in, they’d see a full-color catalog of his products; only “people of fashion” would be permitted to see the actual items, hidden at the back of the room. In this way, he engineered an aura of exclusivity and scarcity.

“Once the world was out that a limited number of new vases were available to the privileged,” writes Dolan, “the price would simply reflect the idea that only people of status had real taste”

It was a brand new principle of marketing: “Deny the majority the ability to purchase art, then use their lack of means as inadequate taste.” Once an item would “grow stale” with the upper crust, he’d cut the price and market it to the wider, aspirational class.

And Josiah didn’t stop with England. He realized there was a similar consumer revolution unfolding in America — and that, despite a mounting tea frenzy, there wasn’t a single potter in the 13 colonies to fill the demand. From a port in Liverpool, he grew a healthy export business; even George Washington was said to have ordered a set.

He’d built the first luxury brand the modern world had ever seen.

“Great artists steal”

Josiah realized that in this new era of conspicuous consumption, “every rarity soon grows stale.” Like all great innovators, he strove for permanency but understood the novelty of his inventions was ephemeral.

Nearly everything Josiah created was almost instantly copied by a cadre of other potters who leeched off his success. His solution to this was multi-tiered: 1) He constantly blitzed the market with new products, and 2) He developed new ways to sell them.

He sensed a growing demand for antiquities, and started making pottery that “pottery that reminded the new money of the rustic life they left behind.” He invented a new form of porcelain called “jasperware.” He pioneered new glazes, new designs, new firing methods.

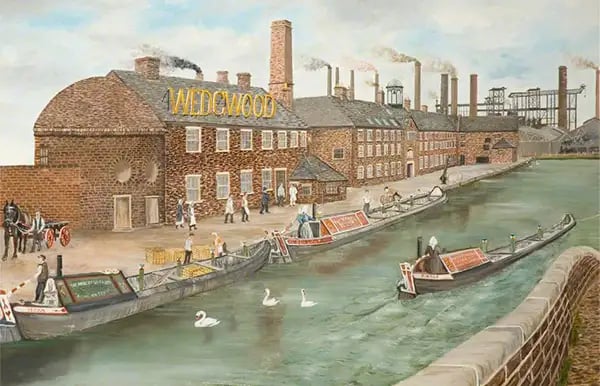

At the time, logistics were not ideal: Crates of pottery would be transported by horses on bumpy roads and pieces were often broken in transit. He was the first merchant to offer both free delivery and free returns on broken goods. At the same time, he lobbied for the creation of a major transport canal that would cut down on losses.

Long before the rise of door-to-door salesmen, Josiah sent workers around London neighborhoods to “cold-sell” his products and drum up demand.

These salesmen would cart around “hand-annotated catalogs” with full-color images of his offerings, along with samples of his glazes on tiles. More crucially, they would “provide direct feedback from retailer to designer on market trends and on which patterns would benefit from amendment.”

If Josiah’s customers weren’t satisfied, he’d offer them free returns, knowing full well that trust the gesture gained outweighed any lost inventory.

The Googleplex of its time

The rise of Josiah’s business fortuitously coincided with the Industrial Revolution: Machines were changing the nature of work, including pottery.

In 1769, with the help of a cash infusion from his wife’s wealthy family, Josiah opened Etruria — one of the first modern factories ever constructed in England. And long before the “company towns” of Silicon Valley, he set about creating an insulated community for his staff.

His employees, whom he called ‘Etrurians,’ were the Googlers of their time, and he offered them housing in 42 units built next to the factory. It was, by the industrial standards of the time, a “model community” with strictly enforced rules: No drinking, no gambling, no obscene language.

Like Steve Jobs, Josiah ruled his domain with the ego of a perfectionist: He’d walk through the factory floor smashing any inadequate pottery with his cane. Workers became accustomed to his favorite line: “This will not do for Josiah Wedgwood.”

Efficiency was tantamount: He instituted the first “punch-in” clock and was an early adopter of the division of labor.

In turn, he “rewarded” workers with a crude form of health coverage and retirement, daycare for their children, and classes. His vision was at once good-natured and imposingly paternal: He wanted to cultivate entrepreneurial minds.

The potter meets his urn

By the time Josiah died in 1795, he’d amassed a fortune of £600k pounds (more than US $100m today), and was the 4th richest man in all of England.

He was cited as one of the most important manufacturers in the kingdom’s history, an “ingenious and industrious man” who had become a “national source of wealth.”

Passed down for generations, his company, Wedgwood, continues to exist today Though it has since transferred ownership, its longevity is a testament to the power of his brand.

Like pottery, we’ll all return to dust one day. Factories will crumble. Inventions will rust into irrelevance. But as Wedgwood reminds us, good branding and the spirit of experimentation can transcend time.