There is no end to America’s most egregious case of shrinkflation

Paranoia sets in when the package arrives at my door. Is that pest control van across the street filled with private investigators on a stakeout? Has that antenna always been on my neighbor’s roof?

A few weeks ago, I was just like you, taking a summer vacation to the beach, anxiously waiting for new episodes of “Presumed Innocent.” Then, after reading too many stories about fast furniture, Chipotle’s shrinking burritos, and other examples of corporations diluting the size and quality of their products, I fell down the wrong rabbit hole.

Next thing I knew, I was in touch with a secret source on a black market called eBay. She goes by MrsFreeThinker and frequents estate sales, where she’d found the contraband I needed. Somebody had kept this secret to the grave.

Inside my house, I draw the blinds and rip into a gray plastic bag. It’s everything I hoped for: a factory-sealed four-pack of regular Charmin Ultra toilet paper produced in 1992.

I look at the fine print and gasp…170 sheets per roll!

These days, a regular Charmin Ultra Soft roll, if you can find one, has 56 sheets. Even the roll they market as “Double” doesn’t have 170 sheets — it has 154. And the 1992 rolls are hardly the largest — the back of the package includes a note from parent company Procter & Gamble explaining these rolls have fewer sheets than a previous version.

Toilet paper is shrinkflation at its absolute worst. Imagine if Chipotle spent decades reducing the size of its burritos until they looked like tacos.

How far does the downsizing go? And why has the industry managed to make its products so small with barely any scrutiny?

The 650 sheet toilet paper roll

Once I’d purchased the toilet paper off eBay, I called Edgar Dworsky to help unroll the mystery of toilet paper shrinkage.

Dworsky, a Massachusetts-based consumer advocate who runs the consumer education websites Mouse Print* and Consumer World, is perhaps the only person in the US who reads the fine print, and he’s certainly the only one who’s consistently tracked changes to the sizes of products like cereal, snack chips, frozen pizza, and coffee mix, becoming the go-to shrinkflation source. As companies sought to avoid price hikes during the last couple of years and opted for shrinkflation, Dworsky’s decades-long work was profiled by the New York Times and praised by John Oliver.

Edgar Dworsky is the nation’s leading shrinkflation expert. (Joanne Rathe/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

When it comes to downsizing products, Dworsky tells me that toilet paper, along with paper towels, “probably come in first place.” And my 1992 toilet paper is just the tip of the iceberg.

He started collecting toilet paper around the 1970s. Back then, Charmin’s regular roll had 650 sheets of single ply toilet paper…650! By 1975, the roll shrunk to 500 and then to 400 in 1979.

Dworsky says that back in the ‘80s he had products that showed Charmin’s sordid shrinkage history — until he lent his toilet paper to a local reporter.

“She wound up taking them home and using them,” he says. “[I was] like, ‘You used my antique Charmin? The one-of-a kind stuff?’”

A Charmin ad from 1966 with 650 sheets per roll. (Raleigh Register via Newspapers.com)

Charmin was far from done, anyway. By 1986, the sheet count had dropped to 380. On eBay, I found nearly identical 1988 Charmin packages — one contained 300 single ply sheets per roll and the other had 280.

Soon, Procter & Gamble would offer Charmin in a double-layered two ply — like my 1992 roll that contains 170 sheets — and has largely shifted away from single ply rolls.

It wasn’t the only brand to engage in shrinkage. Although Scott 1000 must keep 1k sheets per roll to live up to its name, Dworsky has tracked the toilet paper’s weight. Four rolls, he discovered, weighed about two pounds 10+ years ago. They now weigh barely over a pound.

The size of Scott’s sheets has also declined from 4.5 x 3.7 inches to 4.1 x 3.7 inches. Charmin’s sheets have gone from 4.5 x 4.5 inches to 3.92 x 4 inches.

“They know consumers are not net weight conscious. They know they’re price conscious,” Dworsky says. “So if they can try to avoid raising the price by giving the consumer less, that’s what they do.”

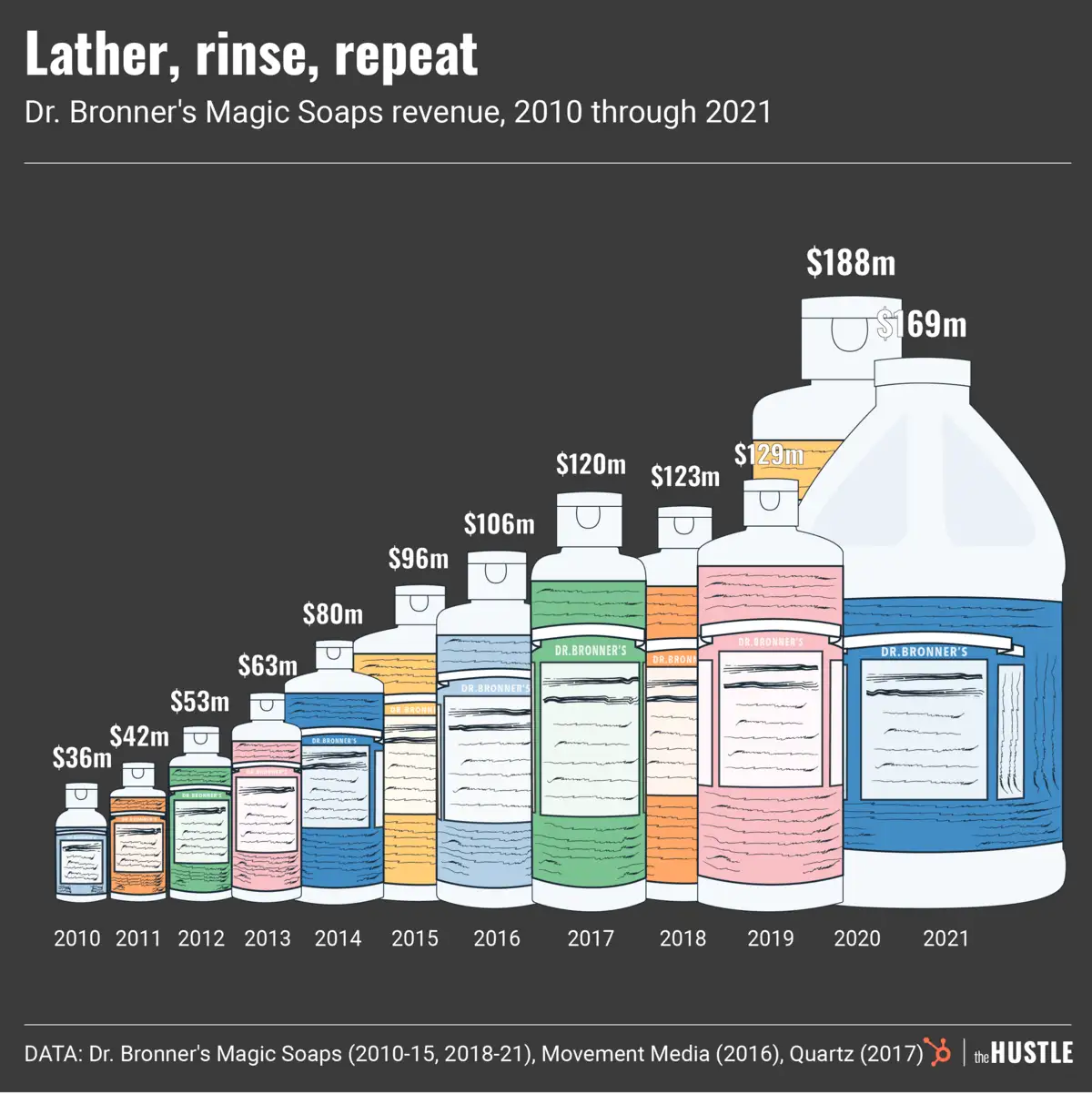

The Hustle

Procter & Gamble has claimed Charmin has become thicker, stronger, and more absorbent. (Procter & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark, the parent company of Scott 1000, didn’t respond to my interview requests.) The note from P&G on my 1992 toilet paper said Charmin Ultra had shrunk “because it is so thick we couldn't put as many sheets on and keep the rolls the same size.”

Uh-huh.

With the constant downsizing, Dworsky notes, “at some point the product gets obnoxiously small and that brings complaints to the forefront. They have to find some way to reintroduce a larger size.” Charmin, for instance, started selling “Double” rolls around the late ‘90s. These rolls had 2x more sheets than the ‘90s regular roll but far fewer than a 1970s regular roll.

The same strategy has played out in the ensuing years as the “Double” was heavily downsized, and shelves filled with “Mega” and “Super Mega,” neither of which are as large as regular rolls from the ‘70s or ‘80s.

These superlatives have helped conceal blatant shrinkflation.

- A pack of 12 Charmin Ultra Soft “Double” rolls — now mostly unavailable in stores — were said to be the equivalent of 24 regular rolls. It contained 201 square feet of toilet paper.

- Six Ultra Soft “Mega” rolls — introduced after the “Double”— are also supposedly the equivalent of 24 regular rolls and feature 70 more sheets per roll than the “Double.” Yet the package contains just 146 square feet of toilet paper. (Since 2022, the “Mega” sheet per roll count has fallen from 264 to 224.)

The Hustle

Perhaps most confusing, Dworsky says, these products “do a comparison to a non-existent version.” That’s because regular-sized rolls have been virtually impossible to purchase for years — Dworsky might have one of the last.

He bought a pack of regular two ply Charmin rolls manufactured in 2013. The sheet count, which, again, totaled a mighty 650 a couple generations ago, had dwindled to 82.

He sent me a photo of the roll positioned next to a dollar bill standing upright. They were about the same width.

Wood pulp volatility

After talking with Dworsky and trawling through newspaper archives, I’d begun to absorb the sheer magnitude of toilet paper shrinkage. But I still needed to know why. Why did the toilet paper companies play this game?

I went as close to the source as possible, to Brian McClay and D'arcy Schnekenburger at TTOBMA. They track, analyze, and publish actual transaction-based net price indices for the single most important ingredient for toilet paper: wood pulp.

- Toilet paper is typically made from two varieties of pulp: eucalyptus hardwood and northern softwood, which are sourced and produced in countries such as Canada, Brazil, Uruguay, Indonesia, and Finland.

- Counterintuitively, hardwood pulp gives toilet paper its soft feel, and softwood pulp gives it strength and heft.

Until the 1980s — around the time Charmin kicked its shrinkage into overdrive — pulp prices were fairly consistent, says McClay, who started his career as a wood pulp statistician in 1978. But volatility has been the norm since then with increased globalization, climate change-driven supply shocks (caused by bugs and fires and droughts), and the entry of China as a huge buyer (and sometimes supplier) of pulp.

In early 2016, Northern Bleached Softwood Kraft pulp, a premium paper-sheet reinforcement pulp made from sawmill chips, sold in North America for ~$550 per metric ton. In 2022, the price topped $1k — before sliding to ~$600 last year and then climbing back up to ~$900 earlier this year and falling over the last few weeks.

The Hustle

Major toilet paper brands that need consistent supply have few protections from this volatility. Whereas many commodity markets have futures contracts that allow buyers to hedge against price fluctuations, toilet paper producers typically sign softwood pulp contracts tied to an index such as the TTO, paying a price from a negotiated starting point that moves with the TTO monthly index.

On top of that, many companies, especially in China, play “the inventory game,” McClay adds. They buy huge quantities of pulp on spot when prices are low — sending the price upward — and avoid buying at the higher rates, sending the price back down.

“It is material enough to move the global market,” McClay says. “Everybody’s a China watcher in our business.”

In China and South America, where there are fewer premium brands and more white label toilet paper products, toilet paper companies adjust to expensive softwood prices by changing their recipe, sometimes switching out softwood for cheaper bamboo pulp.

The composition of toilet paper in these markets is ~90% hardwood and ~10% softwood, according to Schnekenburger. Such a balance also helps toilet paper companies save money, as hardwood is consistently less expensive than softwood.

But North American toilet paper companies, particularly premium brands like Charmin, Cottonelle, and Quilted Northern, need the softwood. They typically have a ratio of ~70% hardwood and ~30% softwood, says Schnekenburger, to meet a “higher expectation for strength.”

“They won’t even change the supplier of their softwood if they can help it,” he adds. “For them consistency both in their operations and consistency of product are more important than anything else.”

Softwood is piled up at a pulp producer in Germany. (Klaus- Dietmar Gabbert/Picture Alliance via Getty Images)

That thinking, according to Shelley Vinyard, a corporate campaign director for the National Resources Defense Council and leader of its Issue With Tissue reports, has also been brutal for forests where pulp is sourced. Many smaller North American brands, such as Who Gives A Crap and Seventh Generation, use bamboo or recycled paper instead of virgin pulp. But the report found legacy brands like Charmin, Scott 100, and Quilted Northern used few, if any, sustainable ingredients.

“What they’ll say is that they need this [wood pulp] fiber in order to provide the softness and strength that their consumers demand. But honestly I don’t buy it,” Vinyard says.

“If you look at the growth of the sustainable tissue market and if you think about the size of the R&D budgets of a company like P&G, you’d have to think they could shift their sourcing practices and develop technology to deliver the performance levels their consumers expect.”

Bamboo and recycled paper can often be purchased for less than virgin pulp. As of last year, Who Gives A Crap’s cost per sheet was a few cents lower than offerings from Charmin, Quilted Northern, and Cottonelle.

Still, that didn’t mean Who Gives a Crap had avoided all the worst instincts of the major players. On its website, I couldn’t find any regular rolls for sale. The company only sold the “double.”

No legal consequences

I understood the pressures faced by the toilet paper companies. They’ve faced volatile supply costs and believe too many of their consumers would react poorly to changes to their formulas. But why hadn’t anyone put pressure on their downsizing?

A long time ago somebody tried.

In 1975, when people noticed Charmin reduced its rolls from 650 sheets to 500 sheets, James Lack was incensed. A consumer affairs commissioner in Long Island, he considered Charmin’s justification — that “a new improved softness” led them to shrink the number of sheets lest the rolls not fit on toilet paper holders — “one of the worst examples of advertising hype I’ve ever seen.”

Charmin didn’t even seem to have its story straight. When journalists from Long Island’s Newsday questioned a Procter & Gamble spokesperson about the new toilet paper rolls, he said they had as much or more wood pulp as the prior version. But that response contradicted a note to investors that claimed the 500-sheet rolls used less wood pulp.

Lack vowed to investigate Procter & Gamble and requested investigations from the FTC and FCC over deceptive advertising. The story was published in dozens of newspapers. Maybe shrinkflation would be nipped in the bud!

But nothing happened.

The Hustle

Lack didn’t have much of a case, and neither has anyone else in the following decades. While it may seem deceptive to shrink toilet paper with little notice aside from the fine print — and to compare “Mega” and “Double” rolls to basically nonexistent products — it’s not against the law. Companies can shrink their product and charge the same amount, or more, while doing nothing to warn consumers aside from updating the fine print.

The new publicity around shrinkflation has at least caught the attention of legislators. Two new shrinkflation bills have been introduced this year. One would give the FTC power to punish shrinkflation and another would force companies to notify consumers when they shrink products while keeping the price the same. France enacted a similar law a few months ago.

Absent new protections, though, toilet paper will keep getting smaller and rebranded with deceptively larger names that actually contain less product. “There is no end,” Dworsky says.

He’s already spotted Charmin’s latest stunt: The company has swapped out “Super Mega” rolls for “Mega XL,” a rebrand with the same number of sheets. Dworsky suspects Charmin fears running out of descriptors and wants to save the mother of all superlatives, “Super Mega,” for the next time its shrinkage has gone too far.

“I mean, seriously, what can you do to Super Mega? Become Super Super Mega? Super Mega Plus?” he says.

The toilet paper companies will find a way. They always do.

Consumer Products