Running across a DeLorean on the road is like spotting a rare bird in the wild: The brushed stainless-steel exterior, the gullwing doors that open toward the sky. It’s the souped-up sports car that needed 1.21 gigawatts of electricity to take Michael J. Fox back to the future. You can’t help but stare.

It’s a strange vehicle with an even stranger automotive history.

Heralded as revolutionary upon its release in 1981, the car sold poorly and was plagued by mechanical problems. It didn’t help when its charismatic creator, John DeLorean, got mixed-up in a $24m cocaine bust.

While the products of most failed companies fade into oblivion, the DeLorean has held onto its head-turning allure nearly four decades after its debut. It’s a debacle that spawned a legend.

And if Stephen Wynne, a Texas entrepreneur, gets his way, you will soon be able to buy a brand new DeLorean — one that makes up for the shortcomings of the original and picks up where its namesake left off.

A legend is born

Before he named a car after himself, John DeLorean was a bright young engineer at General Motors who aggressively pushed the automotive giant to appeal to younger, hipper customers.

In the 1960s, DeLorean moved the company’s Pontiac division away from the boxy behemoths it had been producing and pioneered sexy numbers like the Tempest, the GTO, and the Firebird. At 40, he became the youngest division head in GM’s history.

Along the way, he also acquired a reputation for being brash, not listening to higher-ups, and working every angle to get his way. After an unedited version of a speech he made criticizing GM execs leaked to the press, he was out of a job.

So, DeLorean decided to start his own car company.

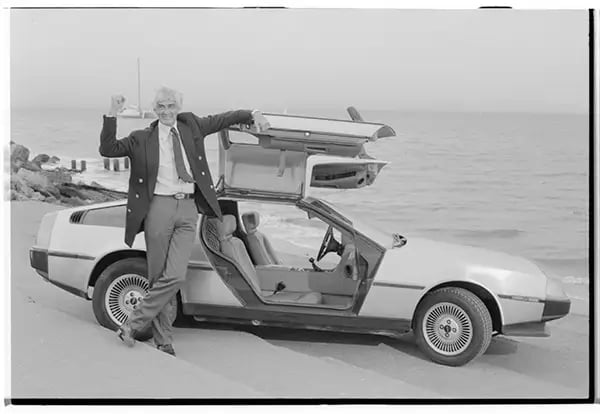

John DeLorean poses with an early DeLorean car in San Francisco in the early 1980s (photo: Roger Ressmeyer/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

Launched in 1975, the DeLorean Motor Company sought to build a sports car unlike anything else on the road.

With his resume, DeLorean was able to secure $200m in funding ($950m in 2019 dollars), with backing from the British government and celebrities like Johnny Carson and Sammy Davis, Jr. He constructed a 660k-square-foot manufacturing plant in Northern Ireland and, by 1981, was rolling cars off the line.

The DeLorean was initially met with great hype — but its then-pricey $25k price tag, coupled with a myriad of mechanical issues, resulted in less-than-stellar sales.

When the company ran dangerously short of funding and his investors refused to cough up more cash, DeLorean turned to drastic measures.

In 1982, a man DeLorean knew casually approached him about getting involved in a $24m cocaine deal; determined to keep his company afloat, he took the bait. That man turned out to be an FBI informant, and the supposed cocaine deal turned out to be a set-up. DeLorean’s lawyers argued that the government had entrapped him and, after a trial that played out on evening news broadcasts and in the tabloids, he was acquitted.

But by then, the damage was done: The DeLorean Motor Company went bankrupt, and its disgraced founder withdrew from the spotlight.

Then, along came Stephen Wynne

Growing up in Liverpool, England, Stephen Wynne was obsessed with the cars he saw in American magazines. With the DeLorean, it was love at first sight.

“It was a drop-dead design,” he says. “And it was at a time when the automotive industry was very boring and this was a game-changer.”

Stephen Wynne (photo: Fascinating Nouns / Daniel J. Glenn)

Wynne emigrated to the United States, where he opened a repair shop in Southern California specializing in British and French cars. In the early 1980s, customers started showing up with DeLoreans, which had been rushed to market and were saddled with a bunch of nagging issues. Those iconic doors, for instance, sometimes failed to open, trapping occupants inside.

In due time, Wynne became the go-to DeLorean mechanic country-wide.

After the auto company went belly-up, he bought a warehouse filled with leftover DeLorean parts and had the ridiculously massive haul shipped from Ohio, to Texas, an almost military-level logistical operation that required more than 80 semis.

In the wake of the DeLorean Motor Company’s bankruptcy, Wynne also acquired the rights to the firm’s name and intellectual property, made himself the CEO, and decided to resurrect the beloved but beleaguered car.

Over the years, Wynne has watched as the reputation of the DeLorean has cycled through ups and downs.

”The first decade was dealing with the shame of a bankruptcy and drug dealing,” he says. “The second decade was dealing with people thinking that it was a movie prop, that it was just a time machine. Now that we’ve got over that and the values are coming up, people are treating it like a real car.”

Wynne built his headquarters in Humble, Texas, just outside of Houston.

When you drive by, you might see a parking lot filled with DeLoreans. At any one time, he has 40 or so DeLoreans on the premises, and most days some dazzled passer-by will wander into the shop and start asking questions (“I unfortunately don’t have a tour guide on staff,” he says).

Inside you’ll find floor-to-ceiling shelving units filled with the 2,650 parts needed to construct a DeLorean from scratch; Wynne estimates he still has somewhere around 4m original parts in stock, from filters and flanges to engines and steering wheels. He also has DeLorean’s blueprints, so they can manufacture whatever parts they need.

It’s more like a mini-factory than a fix-it shop.

DeLorean cars fill the shop floor in Humble, Texas, and thousands of parts line the shelves (photos: DMC Facebook page)

While Wynne’s business is servicing the older cars, what he really wants is to crank out an upgraded model and take the DeLorean to the next level.

He’s not going to replace the doors or the exterior with something more practical. Nor is he going to tweak the car’s iconic silhouette. After getting to know pretty much every serious DeLorean aficionado (including Ernest Cline, the author of Ready Player One), Wynne knows what makes the car beloved.

What he does want to do is improve on all the ways the original fell short.

When the DeLorean first rolled off the assembly line, its engine was pitifully underpowered. It looked like a rocketship but puttered like a sedan, which didn’t exactly help sales. An otherwise positive review from Car and Driver pointed to manufacturing defects, complaining that “switches popped loose” and “windows fell out of their tracks.”

Wynne plans to more than double the horsepower. He’ll also jazz up the spartan interior and iron out all the other kinks that DeLorean and his engineers never got around to.

“After working on the car for nearly 38 years, we know what needs to be done,” he says. “It’s a wonderful opportunity to make a car they never got to make.”

Right now, though, that opportunity is in limbo

There are plenty of customers who want nothing more than to drive a new DeLorean off the lot. Several thousand of them, in fact.

They tend to be more geeks than gear-heads — guys who wanted to buy a DeLorean when they first came out, but couldn’t afford the $25k price tag. Other would-be buyers were born long after the company’s collapse but still dig that futuristic throwback vibe. The waiting list has grown beyond what Wynne will ever be likely to fulfill.

A row of DeLoreans sit outside the DeLorean Motor Company in 2013 (photo: Paul Bersebach/Digital First Media/Orange County Register via Getty Images)

But the glacial pace of the federal bureaucracy has tempered Wynne’s ability to act on this demand.

In December 2015, President Obama signed the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST), which, among other things, allows small manufacturers like DeLorean to produce a limited number of cars each year. Under the act, DeLoreans would be classified as “replicas” and wouldn’t have to meet the full list of modern safety regulations governing new cars.

Here’s the snag: Before the cars can be built or delivered, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has to tell Wynne and other manufacturers precisely what they can and can’t do. Those guidelines were due way back in 2016. Somehow it still hasn’t happened, and Wynne is understandably frustrated.

“We’ve been on hold and we keep saying ‘It’s coming, it’s coming,’” he says. “We’re starting to lose the faith of a lot of potential vendors and partners. They’re starting to think that we’re full of crap.”

Recently, there has been some movement in the right direction. A lawsuit helped prompt the NHTSA to issue a set of draft regulations, which must be discussed and revised. If all goes well, it could be a matter of months before the new DeLoreans get the greenlight.

Wynne’s trying not to get his hopes up.

“I spent over $1m four years ago and then had to put everything on hold. It cost me a lot of capital in goodwill as well as money and I’m just gun-shy,” he says. “I don’t want to get too excited.”

The call of the DeLorean

What is it about this particular car that captures Wynne’s imagination?

“It goes back to the original concept, which was an ethical sports car. And that part of it they got absolutely right,” he says. “They wanted the cars to last beyond the traditional 5- to 10-year cycle. That’s what’s behind the stainless-steel body. It has absolutely stood the test of time.”

The saga of the car has always been tightly bound up with the rise and fall of its creator. For years, DeLorean, who died in 2005, didn’t have much to do with the community of fans that grew up around his car. Perhaps it was a reminder of all that had gone wrong in his personal and professional life.

Stockpiled DeLorean cars at the DeLorean motor plant in Belfast in the early 1980s (photo: PA Images via Getty Images)

But with the encouragement of his daughter, DeLorean started showing up at meetings of DeLorean enthusiasts, shaking hands, taking photos, autographing the car he created.

“At the conventions, he was an absolute hero. He was totally mobbed. He was a god,” says Wynne, who met DeLorean several times. “I think it was nice for him to have seen and experienced that.”

Two recent biopics (“Driven” and “Framing John DeLorean”) grappled with DeLorean’s legacy, shedding light on the fine line between visionary and egomaniac.

Like plenty of worldbeaters today with a clever app and an elevator pitch, DeLorean was determined to disrupt a slow-moving industry. He mocked the naysayers and traded on his considerable charm. He married a supermodel, Cristina Ferrare, and posed shirtless for magazines. He also burned through ~$175m at a jaw-dropping clip.

Wynne’s own view of the man is complicated. The story of DeLorean, as it’s usually told, is of an entrepreneur so determined to realize his dream that he fell in with an unsavory crowd. Another version is of a guy whose recklessness helped torpedo a company that might otherwise have thrived.

“I am a huge fan of the DeLorean brand. I’m a huge fan of the DeLorean company,” he says. “But I am not a huge fan of John DeLorean.”

That may be why Wynne hasn’t bothered to watch the two new movies about DeLorean. He was invited to one of the premieres but didn’t go. He’s not interested in reliving the drug trial or plumbing the depths of John DeLorean’s troubled soul.

“For me,” Wynne says, “it’s always been about the car.”