Ten years ago, Cindy Thomason was walking down the stairs at home when she heard her phone ring.

On the other end was an executive from Warner Bros. Entertainment, calling to let her know that a font she designed would be featured in the upcoming blockbuster adaptation of The Great Gatsby.

“I had to sit down,” Thomason says. “I’m just somebody who decided to design a font on a whim.”

A nurse in suburban Virginia, Thomason began tinkering with fonts in her free time using a software package she bought for $100. She’d listed the font, which she named Grandhappy, on an online marketplace called MyFonts.

That’s where producers from Warner Bros. found it, and bought it to use as Jay Gatsby’s handwriting in the 2013 film.

It should have been a dream come true, a big break for a hobbyist font designer. But Thomason’s cut for her design’s feature-film cameo was a whopping $12 — not even enough to recoup what she paid for her design software.

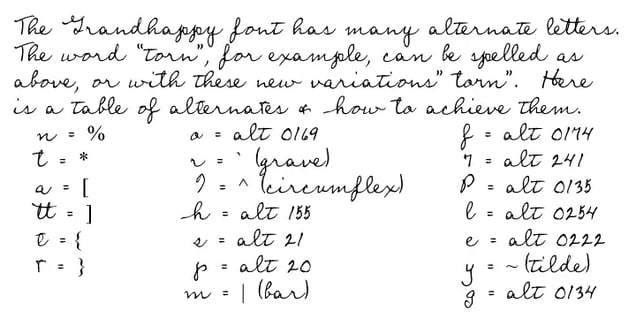

Alternate letters designed by Thomason for her Grandhappy font (Cindy Thomason)

Thomason’s story isn’t an anomaly: Fonts are a ubiquitous commodity. Every font you see — on your computer screen, a street sign, a T-shirt, or your car’s dashboard — has been crafted by a designer. With 4.5k independent artists selling on MyFonts today, many struggle to attract customers and to make a living in an oversaturated market.

It’s only getting harder, as designers must compete with and abide by the terms of one company that’s approaching behemoth status: Monotype.

The company owns not only many of the world’s most popular fonts but also exchanges like MyFonts where font designers bring their work to market.

The industry is inching toward a monopoly, and it’s leaving independent designers with fewer places to go.

Written history

In 1440, when Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in order to mass-produce Bibles, his books came with another innovation: the first font.

For the next several centuries, countless foundries sprung up to mimic the characters forged on Gutenberg’s metal plates, experimenting with typefaces and new fonts (a typeface is the umbrella category for a uniquely designed set of letters, such as Times New Roman; a font is a specific variation of a typeface, such as Times New Roman in 16 point bold).

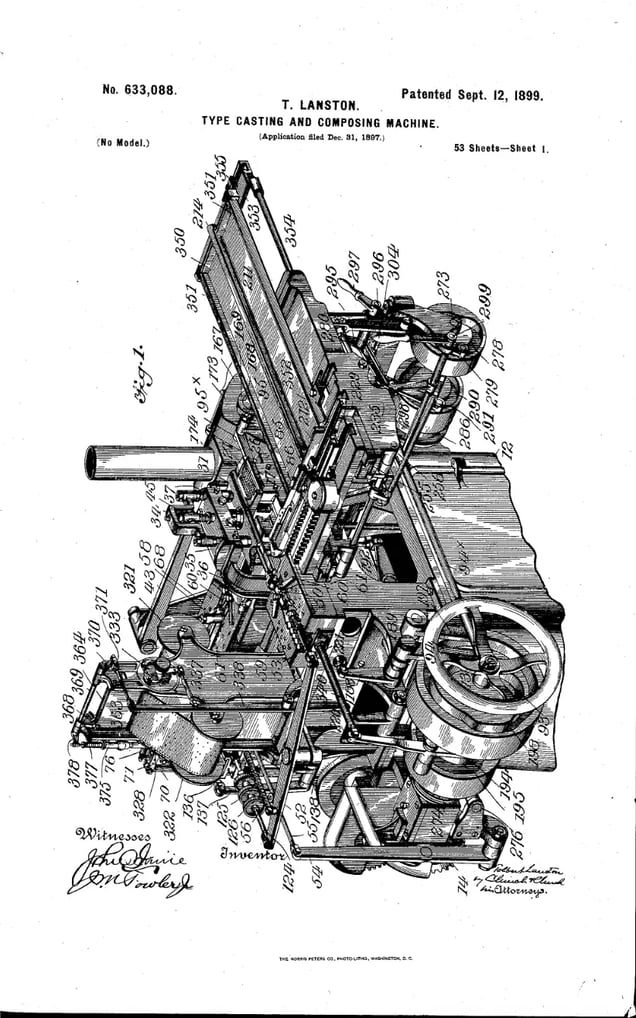

Monotype arrived at the end of the 19th century. The company was founded in Philadelphia by Tolbert Lanston, whose monotype machine invention allowed for increased speed and efficiency when producing type. Over the next few decades, Monotype, by then with branches in the US and the UK, developed popular typefaces such as Gill Sans, Perpetua, and Times New Roman.

A type-casting machine patent filed by Monotype founder Tolbert Lanston. (US Patent and Trademark Office)

In the last half of the 20th century, the font industry, always volatile and rife with mergers and acquisitions, went through rapid change. The mechanized process of Monotype’s signature machine faded out, replaced by phototypesetting and then digital typesetting, bringing fonts to screens.

Monotype endured financial difficulties and restructurings, eventually being acquired by the Boston private equity firm TA Associates in 2004 and going public with stock-ticker name TYPE in 2007. The retooled Monotype saw its annual revenues climb from $107m in 2010 to $247m in 2018 and became a powerhouse:

- In 2006, it purchased Linotype, a major competitor since the 19th century, bringing Helvetica, Avenir, and ~6k other typefaces into its fold.

- It bought Ascender Corporation, a digital typeface foundry, in 2010 and FontShop, which owned more than 2.5k typefaces, in 2014.

In 2019, private equity firm HGGC bought Monotype for $825m, acquiring its roster of typefaces and setting it up for even more acquisitions. The company has since purchased URW Foundry and Hoefler & Co., a renowned independent foundry.

According to Quartz, Monotype has claimed its purchases made life better for customers, who only have to navigate a licensing agreement from one company to access a bevy of fonts. But one font designer believed the acquisition of Hoefler & Co. felt like “a kraken eating up the industry.”

“A market with one very large player and a lot of smaller players is not a healthy market,” Gerry Leonidas, professor of typography at the University of Reading, told The Hustle. “It essentially stifles the competition and makes it difficult for alternative models to grow.”

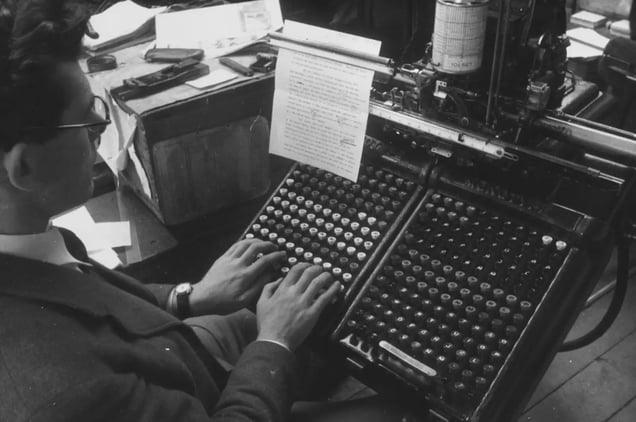

A man uses a monotype machine in 1938. (Getty Images/Kurt Hutton)

While boutique foundries still exist and do work for big companies, Monotype owns most major fonts: Arial, Helvetica, Gotham, Times New Roman. Its main competitors are Adobe Fonts and Google Fonts, the latter of which gives away fonts for free.

In addition to the giants, there are thousands of other designers, some hobbyists and some full-time font makers, who try to sell their typefaces. Most of them have to go through — you guessed it — Monotype.

Competing with Monotype

In 2012, Monotype made one of its most noteworthy acquisitions. It paid $50m for the parent company of MyFonts, the website where Cindy Thomason and other independent designers and foundries hope to sell their fonts to the likes of independent graphic designers, ad agencies shopping for client projects, or major brands.

- The MyFonts marketplace features 4.5k foundries selling more than 250k typefaces. Other marketplaces like Creative Market and Etsy feature 82k and 5k+ fonts, respectively.

- Foundries set their own prices. The average font costs $29 and sells per use or in perpetuity, depending on licensing agreements.

Monotype tells The Hustle that of the thousands of foundries selling on MyFonts, about 55% say their earnings provide passive income, while 45% report earning a living selling fonts.

Much of their earnings go back to Monotype, which takes a 50% cut of every sale on its site. (Creative Market similarly takes a 50% commission fee, while Etsy charges 20 cents per listing and takes a 6.5% fee for every sale.)

Although other marketplaces take smaller cuts, MyFonts is known in the industry for being the gold standard for audience reach. Ellen Luff, who runs Ellen Luff Type Foundry and whose Larken font (starting at $42) is a MyFonts bestseller, told The Hustle there’s little choice but to use the site.

“When you’re independent, you’ve got your freedom, which is great. But then you have to balance being overlooked, and trying to beat [MyFonts] because they are a monster,” she said. “They are huge.”

The power of Monotype and MyFonts isn’t the only obstacle for independents. Luff has spotted her fonts being used by corporations such as Apple and NASA, sometimes without her permission.

Luff says half of her clients come from retrospective licensing agreements made after she’s found her designs being used illegally. But going up against large companies is no easy feat for independent designers who have no legal teams to support them in negotiations.

A display of old type at Monotype’s offices in Woburn, Massachusetts. (Getty Images/Boston Globe)

For designers who partner with Monotype, though, the company puts its power into handling infringement issues. That’s why, for many designers, MyFonts pays off.

Sam Parrett, typeface designer and owner of Set Sail Studios, has a bestseller on MyFonts, La Luxes, priced at $29 for a pack of two fonts. On average, Parrett makes $7k per month through MyFonts sales after the site’s 50% fee.

He says custom work made up just under 6% of his income in 2022, and he takes on about four custom projects per year while he focuses on creating fonts for marketplaces.

And Parrett’s fonts, which he first draws by hand, pop up everywhere:

- Scrawled across actor Gillian Anderson’s naked body and plastered on a billboard for a Peta campaign.

- On the covers of Diana Ross, Katy Perry, and Cardi B albums.

- As logos for multiple Netflix series.

“I drive my wife mad because everywhere I go I’m like, ‘That’s my font!’” Parrett said. “It’s so crazy because it’s just me in my spare bedroom writing these letters.”

Designer Sam Parrett sketching fonts by hand (Sam Parrett)

Paulo Goode, who started out as a hobbyist type designer, says the MyFonts platform helped him launch his career.

“I decided to go full time as an independent type designer less than 18 months after my first release at MyFonts,” he said. “I haven’t looked back since.”

Goode eventually sold the majority of his font portfolio to Monotype.

Is AI coming for font designers?

This month, Monotype plans to introduce a new program that will shift the MyFonts marketplace toward a subscription model.

Rather than coming to the site, finding a font, and figuring out which licensing to pay for, customers can instead opt to pay for a Monotype subscription where the licensing is pre-covered for a larger variety of fonts.

- Royalties will be calculated by taking into account a foundry’s percentage of all ecommerce revenue as well as how often its fonts are used by customers in prototyping and production stages, potentially compensating foundries for use cases that previously went unpaid.

- Those metrics are then multiplied by the amount Monotype bills all its customers for the quarter, and lastly by a foundry’s royalty rate. Foundries have the option to opt into the Monotype Fonts subscription program in addition to normal licensing.

Mary Catherine Pflug, Monotype’s director of partner product and operations, says she believes the plan will help designers earn more by offering payments every time a font is used rather than just for a final product. Plus, she says foundries will have access to more immediate data on their fonts, allowing them to make informed business and design decisions.

Leonidas, the typography professor, says the issue is that Monotype itself owns many of the most popularly licensed fonts and will disproportionately benefit from a subscription structure.

“These things work very well if you are Helvetica — you’ll get quite a lot of money from this. If you have a very good typeface that is used for music publishing or poetry, you might get nothing,” he said. “They’re putting money back in their own pockets.”

Some font designers told The Hustle they fear the move will force them to put more trust into Monotype, surrendering the control that comes with clear payments for each sale and instead relying on the company’s internal calculations.

A wall of Monotype logos. (Getty Images/Boston Globe)

“[Monotype] keeps saying, ‘We are going to simplify it for the customers and get you more business,’ but you’re not getting us more business,” Luff said. “It’s a way of them cutting the pie differently but not necessarily in anyone else’s favor.”

Pflug is resolute that the program will bring positive change.

“The biggest struggle facing indie foundries today is getting their work discovered by and into the hands of creatives, and in handling the challenging nuances of font licensing. We are not competing with foundries — we’re a channel for foundries to reach more customers.”

To add to the complexities, artificial intelligence may put pressure on the already crowded industry. For now, Parrett feels his job is safe from AI.

“There are people saying it’s going to happen at some point, that it’s just a matter of when,” he said. “But it’s a handcrafted artisan industry — AI can’t get the precision right.”

A green sign featuring Monotype’s old stock ticker symbol at its offices in Woburn, Massachusetts. (Getty Images/Boston Globe).

That optimism, however, will likely be tested as Monotype begins dabbling with AI. The company already owns WhatTheFont, an app that uses deep learning to identify fonts from photographs, and it’s added an AI-powered font-pairing feature.

Monotype says it plans to use machine learning and AI to improve how users discover new fonts on its platform — an innovation that will undoubtedly affect foundries, though it remains to be seen exactly how.

Even amid Monotype’s takeover, an influx of free fonts, and the growing threat of AI, there will always be a need for font makers with an appreciation for the craft.

“I think half of what makes art is the story and meaning behind it,” Luff said. “Although AI will be able to make beautiful curves and replicate trends, it won’t have the story. People are looking for the human relation to the words.”

.jpg?width=48&height=48&name=IMG_2563%20(1).jpg)