I spoke to the most hated guy on the internet and something funny happened. By the end of our two-hour conversation, I didn’t hate him.

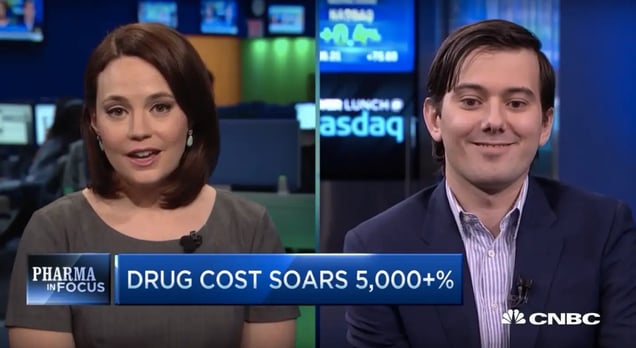

FYI, this is Martin Shkreli, the 32-year-old dude who changed the price of an AIDS drug from $13.50 to $750 and is now under investigation by a senate committee and the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

I’m still wondering whether Shkreli is the monster the world has imagined him to be: a smug, unapologetic asshole. What I saw was more complicated: a man who’s brilliant, calculating, sometimes kind and possibly sociopathic. One determined to rise from his working class roots, willing to be hated, and open to business dealings that are the border of what’s moral and legal. One whose track record indicates that in many cases, he’s not to be trusted.

When I asked him if he would do anything differently, he said, simply, “No.”

ICYMI

I know you’ve seen this story, because it was the biggest thing on the internet last month. People were furious with Martin Shkreli, the CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, after his company jacked up the price of a drug by 5000% overnight. The internet was ablaze with indignation. Hillary Clinton even tweeted about it, setting off a plunge in biotech stocks.

Price gouging like this in the specialty drug market is outrageous. Tomorrow I’ll lay out a plan to take it on. -H https://t.co/9Z0Aw7aI6h

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) September 21, 2015

This wasn’t Shkreli’s first rodeo. He’s been under investigation by the SEC, the cops, the senate, and pummelled with scandals and lawsuits since he was 19-years-old.

It’s been a PR nightmare for his company.

“People tell me, ‘You shouldn’t do that. You shouldn’t tweet that.”

The latest, a federal inquiry

Last week, a U.S. Senate panel launched a bipartisan probe into Shkreli’s company, Turing Pharmaceuticals, and three others, to take a closer look at the way they were pricing lifesaving drugs.

Apart from the insanity of the numbers — the price hike Turing made was from $13.50 a pill to $750 — the drug is used by some of the most vulnerable people imaginable: those who can’t fight off a parasitic infection because they have a weakened immune system. Users of the drug, called Daraprim, include cancer patients, AIDS patients, and pregnant women — people who don’t need anything else to worry about.

“I’ll be your villain.”

At the center of the controversy is the self-proclaimed villain, Shkreli. He’s the poster boy for his company, Turing, and symbolizes everything wrong with the medical industry in America. At 32, he looks like a biotech Richie Rich, with slick hair and navy blue suits. In TV interviews, he sometimes comes off as insensitive, smug, and infuriatingly out of touch. In one such interview, he said the Daraprim price hike was “not excessive at all.”

“I’d be extremely shocked if anyone was worse off because of what we did.”

@MartinShkreli You are basically just a cartoon supervillain, aren’t you? Put a live chicken in your underwear. @SenSanders

— Kate M Galey! (@TheMidnightOil) October 27, 2015

“People want a villain,” Shkreli told me, calmly. “If people derive some psychological benefit from that, then I don’t want to deprive them of it. I’ll be your villain.”

From the beginning

Shkreli was born in March 1983, to parents who immigrated from Croatia and Albania. They worked mostly in menial jobs as janitors and doormen, and lived in the Sheepshead Bay section of Brooklyn, NY.

“We struggled a lot, but I learned the importance of family, the importance of keeping a family together… I definitely didn’t learn anything technical from my parents,” he told me.

Shkreli had siblings but said he distinguished himself early on as the “alpha male” among them.

He was bright and persuasive, and skipped several grades. At 12, he convinced his father to give him $2,000 to invest on the stock market using their family computer and a dial-up modem. He made money for a while, he said, then eventually lost it. It was his first experience investing.

Shkreli was sent to Hunter College High School, a public school for gifted kids in Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

“I went through all the normal high school stuff,” he said. “Fighting with your parents, focusing on the opposite sex more than academics.” He played basketball and was part of a rock band.

He also battled depression.

Shkreli enters the shark tank

Hunter had a special internship program. Through it, Shkreli got an internship at Cramer, Berkowitz & Co., the hedge fund managed by Jim Cramer, host of CNBC’s Mad Money.

“At a young age I saw a lot of investment strategies that worked,” he said. He tried to absorb them all.

He started at Cramer in a clerical role. At 19-years-old he felt confident enough to suggest that the company president, Jeff Berkowitz, should short a biotech stock. Shkreli had researched it and believed the clinical evidence was shaky. Berkowitz took a chance, and the biotech stock fell – as predicted by Shkreli. The firm made millions.

Not long after, the Securities and Exchange Commission opened an investigation to see if the tip Shkreli gave Berkowitz amounted to insider trading. But the SEC found no evidence of wrongdoing.

“I often view stock markets as big gambling machines, if you’re gonna speculate, you have to be prepared to lose. And what a lot of these companies do is so far beyond speculation. They’re almost asking to lose money.”

After graduating from high school, Shkreli studied business at Baruch College in New York, and had what he described as a “very traditional” college experience. But he continued to do work for Cramer.

At 21, Shkreli struck out and got a job with another hedge fund, Intrepid, where he said he proceeded to “repeat my mistakes from Cramer, and pretty much alienate or piss off everyone.” He then quit to start his own hedge fund, called MSMB, in 2006, with $2 million from an investor he’d worked with before.

By that time, Shkreli told me, he had seen a number of different investment strategies and learned not to get tied to one, or as he called it, “too religious.” But he still didn’t do that well.

“It’s basically impossible to be a great investor in your 20s. I haven’t met many people who have really accrued enough knowledge to do it… And running a hedge fund requires you to be more than a good investor… I would say the fund was almost more of an experiment,” he told me.

Shkreli goes into the drug business

By 2010, Shkreli had been making money off the pharmaceutical and biotech industry for a decade. He knew the industry and decided to found his own company, Retrophin, in 2010.

Shkreli has a rare knack for understanding complex medical trials despite having never attended medical school, and people say it’s one of the things that sets him apart.

“He has a very scientific mind,” Ed Painter, the head of investor relations at Turing told me. “He’s smart and he knows the science as well as the PhDs working for him.”

“You give him a science textbook on chemistry, he’d give it back to you in nine months and he’d have it memorized,” one early investor in Shkreli’s first drug company, Retrophin, anonymously told the New York Times. “He’s a sponge for information.”

Blurring the legal lines

When the time came for a Series A funding for Shkreli’s fledgling company, his hedge fund, MSMB, led the round. The $4 million allowed the new pharma company Retrophin to start operations. But it was the start of a tangled relationship that ended in Shkreli’s firing, an internal investigation, SEC filings, multiple lawsuits and a federal investigation into Shkreli.

In February, allegations surfaced that at Shkreli’s behest, Retrophin had disguised legal settlements with former investors as “consulting agreements.” According to the SEC disclosure from Retrophin, Shkreli used company cash to resolve legal claims against himself and MSMB.

Shkreli’s financial escapades at Retrophin involved payouts of millions of dollars and the transfer of hundreds of thousands of shares of Retrophin stock, the company alleged. The transactions sparked a wave of civil lawsuits and a federal investigation of Shkreli by the United State’s Attorney’s Office, Bloomberg reported.

In August, Retrophin launched a $65 million lawsuit alleging that Shkreli created the biotech company and took it public solely to provide stock to his hedge fund investors at MSMB when the fund became insolvent, Forbes reported. The lawsuit demanded Shkreli pay the company back for all the compensation he’d received.

Shkreli denied any wrongdoing and called the civil suit “preposterous” in one interview.

“Retrophin’s filing is completely false, untrue at best and defamatory at worst,” he told InvestorHub of the allegations. “I am evaluating my options to respond. Every transaction I’ve ever made at Retrophin was done with outside counsel’s blessing (I have the bills to prove it), board approval and made good corporate sense. I took Retrophin from an idea to a $500 million public company in three years — and I had a lot of help along the way.”

Shkreli told The Hustle that he plans to strike back with his own lawsuit against Retrophin CEO Stephen Aselage, who “repeatedly stabbed me in the back.” He hasn’t filed it yet.

In his interview with The Hustle, Shkreli accused Aselage of quitting his job as CEO at Retrophin so he could bid against his former employer for the rights to a new drug that the company intended to purchase. Aselage was still acting as an advisor at the time, Shkreli said. Shkreli was ousted and Aselage was rehired at Retrophin not long after.

Aselage’s representative at Retrophin told The Hustle they were declining to comment because of ongoing litigation.

All of the various allegations against Shkreli are complex and the details of the federal investigations haven’t been made public. But Newsweek reported that court records and people with knowledge of the inquiry said it, “involves such a vast number of suspected crimes it is difficult to know where to start.”

And those weren’t the only PR nightmares Shkreli faced at Retrophin.

Allegations of harassment

A sworn affidavit submitted by ex-Retrophin employee Timothy Pierotti to the Supreme Court alleged that Shkreli harassed him and his family for almost a year. Retrophin sued Pierotti in 2013 for $3 million in damages [when Shkreli was CEO] for alleged stealing; the case was discontinued in 2014, the Daily Beast reported.

Pierotti’s affidavit includes screenshots of alleged messages that Shkreli sent to him, his wife, and his son. A letter allegedly received by his wife said, “I hope to see you and your four children homeless and will do whatever I can to assure this.”

Another screenshot showed a conversation between Shkreli and Pierotti’s 16-year-old son.

“Hey, I’m a friend of your father,” Shkreli allegedly wrote after sending a friend request on Facebook. And, when the teen asked why he friended him, he wrote, “Because I want you to know about your dad. He betrayed me. He stole $3 million from me.”

Shkreli gets fired and starts Turing Pharmaceuticals

“I routinely fought with the board (at Retrophin) and was very dismissive of them, but it was really difficult for someone who has $3-4 million shares of the stock to be ousted by someone who owns no stock,” he told me. “But Aselage asked them to fire me and got them to agree… I could have fought it, but I decided it would be better to succeed without them.”

In his last weeks as CEO, Shkreli reportedly bought small amounts of stock publicly and encouraged investment in the company on Twitter, while selling $3 million of his stock privately, according to reports on TheStreet.com.

I asked Shkreli if accusations that he likes to “game” the market as an investor are true.

“I think the capital markets look and function like a game. It’s sort of bad in one sense, but it’s also the reality. Stocks go up and down and you sit there like a gamer, trying to win, which is make enough money. You almost by definition have to use tactics that not everyone is using. That’s the only way to make money.”

He loves games

Shkreli admits he has a penchant for games, and has “been a videogamer since day one.” He loves League of Legends and recently founded eSports gaming team, Team Imagine.

There have been rumors that he tried to buy his way onto a professional team with $1.2 million. But when I asked him, he wouldn’t tell me if it was true.

He has his own live stream on Twitch at CerebralAzzazzin, where he livestreams himself playing games and discussing stock market investment strategies. Last Wednesday, he got banned for 24 hours for violating the site’s rules.

This Monday night, he was back on at midnight New York time, alone in front of his computer discussing the financial future of Chipotle with 150 followers watching. Kind of makes one wonder about the thousands of women allegedly emailing him.

Shkreli admitted that he actually plays into the whole evil villain thing by creating a larger than life online persona. It’s still him, he said, but him at his most aggressive — pumped with steriods.

The Twitter lies

Shkreli recently tweeted that he had received death threats, but told me he made it up, like much of the stuff he posts on Twitter. He said with everyone bashing him, it’s fair game.

“Where I grew up, on the mean streets of Brooklyn, New York, you really don’t talk about someone without expecting to get retaliated against or at least confronted about it,” Shkreli said.

“One of my goals with Twitter is to make sure that the people who have it out for me get frustrated… (I want them to think) ‘Here is this guy we hate, now there is all this good stuff happening to him — and get mad…’ The goal is to incite curious anger from my detractors.”

He said most of his Twitter fights don’t reflect personal feelings of vitriol.

“There’s just something about the internet that makes people crazy,” he said.

“I think face-to-face, in real life, I have, like, two enemies.”

The lies have built up. He’s claimed he fractured his wrist; this appears to be false. He also claimed there’s a movie being made about him; that’s a lie too, he told me. He’s been approached about it – but every documentarian wanted him to bankroll it.

But this part is true:

Turing’s price hike, overseen by Shkreli, was completely legal.

“Governments are more than free to make new laws. They are more than able to pass an anti-drug-company bill.”

Drugs make up about 10% of healthcare spending, Shkreli pointed out. So every company could double the price of its drug and it would only raise premiums by 10%. Then again, Shkreli more than doubled the cost of Daraprim, he increased it by more than 4,000%.

Is it all just a genius marketing campaign to get money and women?

There’s a well known platitude that says people who go into finance don’t do it because they want to cure cancer. Despite all the hate online, Shkreli said he’s earned the respect of the world’s 1%-ers who believe in one thing: making money.

“I’ve never gotten this much attention in my life,” he told me.

After having his face splashed around every corner of the internet, he can now walk into almost any billionaire’s office.

Being hated around the world might sound like a high price to pay for that kind of access, but Shkreli said he has zero regrets.

“It doesn’t hurt that people know who I am… Now if I want a meeting with a billionaire, it happens quicker. A lot of them, if not all, respect me. They say, ‘You did just what I would do.’”

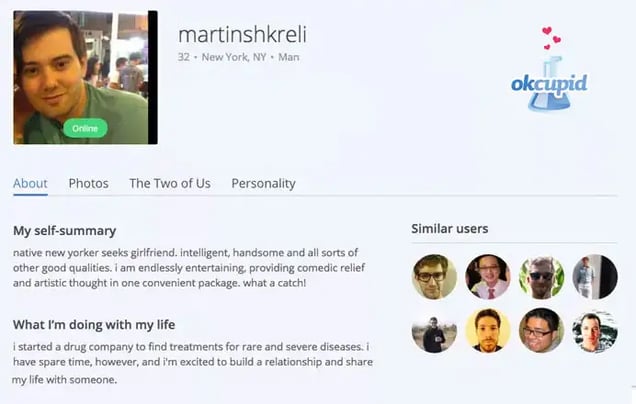

And despite all the hate, he’s been getting a ton of attention from women — thousands of them.

I guess he can cancel that OKCupid account.

But wait, why did he let his drug company Turing raise the drug price so much?

Shkreli said the company needs to make back some of the $55 million it spent to buy the drug. But he also said – repeatedly – that the 2,000 Daraprim patients need a better drug, and that takes R&D; which takes money.

Shkreli told me two people died last year because the Daraprim drug didn’t work for them — a fact I could not confirm. He also argued that other companies have made far bigger price hikes on drugs which treat rare illnesses. There aren’t a lot of consumers for the drugs, Shkreli argued, so of course prices are high.

And Shkreli said he isn’t worried about a $1-per-pill alternative to Daraprim that San Diego-based Imprimis Pharmaceuticals announced they will make. That pill hasn’t been approved by the FDA, so Shkreli doesn’t think doctors will prescribe it.

The reality is, pharmaceutical R&D is insanely expensive. Medical trials can cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

“Medicine needs money and money needs medicine, that’s never gonna change,” Shkreli told me.

Developing a new drug costs $1.3 billion, with a significant portion of the cost coming from regulatory burdens and the FDA’s standard multi-phase trial design, Forbes reported last year.

“You can’t make a drug that people are going to take unless there’s a shit-ton of money involved, and that money comes from dickhead hedge fund managers on Wall Street,” Shkreli said. “There is no true altruism. The path to alleviating all that suffering is through enterprise.”

Some math

To break down the math, if everyone paid the full price, a year of straightforward Daraprim sales would break down like this:

$75,000/bottle x 2,000 patients = $150,000,000/year

But Turing gives away six of every ten bottles for free, or for a dollar a pill. That would mean things would look like this, not counting for the nearly free medication.

$150,000,000 x 40% = $60,000,000/year

The drug reportedly costs $1/pill to make.

Buy a drug people need, then jack up the price

Daraprim isn’t the first drug that was purchased and marked up. The strategy of buying old drugs and hiking up the prices is commonplace in the medical world.

Over the summer, the pharma company Valeant quadrupled the price of its drug Cuprimine, which treats an inherited disorder that causes liver and nerve damage. The New York Times reported that users will now pay approximately $1,800 a month out of pocket, compared to about $366, before the increase.

This year alone, Valeant raised their brand-name drug prices 66% on average, according to a Deutsche Bank analysis.

Valeant is also being investigated by the senate committee.

Retrophin, Shkreli’s first pharma company, has faced similar criticism. It raised the price of a drug called Thiola more than 20-fold. Thiola was developed in the 70s, and is used by people suffering from cystinuria, a nasty kidney disease that causes people to develop kidney stones continuously. There is no cure, and patients need multiple doses of Thiola daily.

Retrophin bought the rights to Thiola drug last May. Back then, it cost $1.50 a pill. Retrophin jacked the price up to more than $30 a pill without changing the formula, according to reports by a University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine professor who wrote for The Street.

The money now

None of Turing’s 200 employees quit since the scandal, according to Shkreli. He told me over and over that people most people who have approached him about the Darprim price hike hullabaloo have actually congratulated him.

“My doormen at my apartment and work tell me, keep on getting that money and fuck the haters,” he said.

Shkreli doesn’t own a car and pays himself “nothing,” he said, but he holds a significant chunk of company stock. He wouldn’t tell me how much. He also wouldn’t tell me his net worth.

But it’s reasonable to assume this is in the millions. He owned 20% of Retrophin, Inc., which traded at $1 billion. And he’s donated $1 million to his high school. And, surprisingly, – and you might view this as irony or altruism, he has contributed to ccrowd funding projects for medical treatment.

He also had enough disposable income to buy a unique piece of Rock and Roll memorabilia: Kurt Cobain’s only credit card. I couldn’t see the exact amount it sold for, but at two days before the bidding ended, the price of the gold Visa card had shot up to $18,600 on paddle8.com.

I asked him why he wanted it in the first place.

“I keep it in my wallet to remind me that this is a guy who killed himself because he became too successful and didn’t even recognize who he was anymore … He lost that authenticity and he couldn’t live with it … People tell me, ‘You shouldn’t do that, you shouldn’t Tweet that. But to lose authenticity is to lose yourself and I won’t do that.”

But wait, are people dying because of Shkreli’s price hike?

Shkreli told me that every patient that needed Daraprim since the price hike has been able to get it. He stressed that insurance companies are the ones paying the full price. Turing Pharmaceuticals knows a lot of people can’t afford the drug, which is why it gives away more than half for nothing or almost nothing.

“Anyone who has trouble getting Daraprim should call me. My cellphone number is published online,” Shkreli said.

This wasn’t intentional – an anonymous hacker posted it to Twitter in response to the price change news.

But some people are having trouble getting their drugs

In September 2015, The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the HIV Medicine Association urged Turing to lower the price of Daraprim. They said patients and hospitals would have trouble affording it at the new price.

Shkreli assured me that no one has gone without it. But a blog on HivClinician.org indicated that some people have struggled to get the drug.

One man reported that he’d got the medication he needed, but the process took a month. “He has finally received (Daraprim) … after initial applications were placed a month ago, with subsequent numerous phone calls and many hours of effort from our clinic Pharmacist,” the blog reported.

“A single bottle of 100 pills is the smallest the hospital can buy and will thus cost $75,000. Both patients will have to be switched (to another medication)…”

And a medical resident at UCSF hospital told me that for many hospitals, the fear may be that insurance companies will stop reimbursing for big-ticket medicines and they’ll be left to foot the bill. That’s also why small nursing facilities might not want to take patient who needs the drug.

One doctor on the forum said they were advising patients to buy the drugs from Canada, where the state-run health care system gives the government actual negotiating power on the price of pharmaceuticals.

The doctor said Canadian pharmacies were selling Daraprim for $145 for a bottle of 90 pills.

So what’s the takeaway here?

There are two ways to see all of this. Both are right, in a way. Both feel incompatible. Shkreli is a bad guy, a kind of pharma bandit. Shkreli is a good guy — at least a good businessman.

It’s worth noting that in our interview, Shkreli didn’t come across like a douche at all. He spent nearly two hours answering all my questions and was far less dodgy and scripted than a lot of execs I’ve interviewed. He glazed over facts that made him look bad, but I was expecting that. And while he came across as egotistical (this is a guy who just started a live YouTube Channel at his desk) it wasn’t the crazy kind of dick wagging you see from him online or in interviews with television stations.

“It’s good because people get to see what I’m like, and most people are like, ‘Oh you aren’t as bad as I thought,’” Shkreli said before cracking up on his live feed YouTube, wearing a black hoodie that made him look like a college student.

In an interview on Halloween with journalist and HIV activist Josh Robbins, Shkreli also came across as a generally decent human being, and — at Robbins’ urging — agreed to lower the price of Daraprim by Christmas.

Here’s what Robbins wrote after his interview:

“…Regardless of how this plays out, there is actually very little doubt in my opinion that Shkreli isn’t as the internet would have me believe. I actually think he cares very much about people’s health. He just believes in making money as well.”

When you look at the facts, Shkreli is not a good guy

He skirts the rules and plays by his own. He’s made his money by shorting stocks and raising the price of medication that suffering people need to live. Then again, shorting stocks plays a role in weeding out bad drug companies. And he’s a businessman. He never swore on a Bible to protect the public good.

That said, I think it is possible that Shkreli really cares about some of the patients he meets in person.

“There are these three kids in North Dakota who are dying of a rare disease that Turing is developing a drug for. They know me. If I was their one hope for surviving this terrible illness, I don’t need joe-blow to like me,” he said.

But there’s a kind of cognitive dissonance when you combine that kind of compassion and still charge $75,000 for a bottle of life-saving medicine — no matter who’s paying for it.

Still pissed at Martin Shkreli?

Take a moment and watch this amazing animated video out of Taiwan, which shows Shkreli riding (and crashing) an electric hoverboard, standing amidst a rainstorm of dollar signs, then getting beat up by vengeful AIDS patients, cancer patients and pregnant mothers.

“It’s no secret pharmaceutical companies are greedy and douchey,” the subtitles begin. “But Turing Pharmaceuticals, founded by Martin Shkreli, is by far the greediest and the douchiest.”

Well… when they put it that way…

If you talk to Martin Shkreli, you realize he’s an evil genius on paper and a geeky, sort of normal person in real life.

We at The Hustle have debated whether his online lash-outs are his sociopathic streak on full display or an incredibly effective personal branding campaign aimed at attracting the adoration of the world’s richest and least scrupulous.

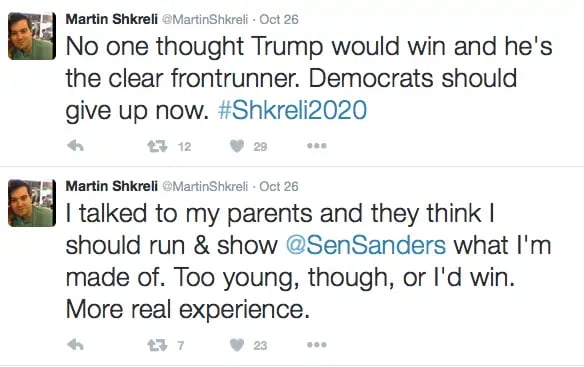

At one point during our conversation, I asked him about Twitter insinuations that he planned to run for president after he posted the hashtag “Shkreli2020.”

He said this:

“Yeah, it’s a joke. I would never run for President. Then again, you look at Donald Trump. I don’t think he ever thought he would run for President. He was just a very successful businessman.”

Shkreli, in the end, is a guy who had the brains and the opportunities, and saw a chance to make millions in a dirty industry — make that two dirty industries. He took that chance. And he’s either chosen not to feel guilty about it, or he never did in the first place.

By the same token, those people who need Daraprim are being screwed by the price increase.

In the meantime, we’ll keep watching. Because we know we haven’t heard the last from this guy.

To close, I’d like to invite you to listen to Shkreli’s favorite song, ‘Soul Survivor’ by Young Jeezy (featuring Akon).