At 2:30 pm on a recent Monday, my dad received a jarring phone call.

A man claiming to be a federal agent (David White, ID #US2607-12) told him there was an abandoned car in El Paso, Texas, rented in his name. Inside the car, they’d found a pile of cash, blood, and drugs. His Social Security number had been linked to 7 different bank accounts, $230k in wired funds, and a rental unit stocked with 22 lbs. of cocaine.

If my dad — a 66-year-old retiree with cancer — didn’t cooperate, Agent White would freeze his bank account and pursue criminal charges.

My dad is not a gullible man. He grew up low-income at the border of Brooklyn and Queens, where street smarts were a survival mechanism. A 30-year career teaching high school students trained him to sniff out bullshit from a mile away.

But minutes into the call, his logic ceded to fear. He was transferred to several other “agents,” who used complex psychological tactics to keep him on the phone and dissuade him from talking to other people. And 4 hours later, he found himself sitting in a parking lot with $3k worth of Target gift cards, reading the codes over the phone.

“When the call finally ended, it was like a spell had been lifted,” my dad told me. “My brain switched back on and I realized I’d been scammed.”

I had to get to the bottom of this: How do these scams work, and who’s behind them? What can be done to prevent them? And why did my dad fall victim?

A $600m-per-year ruse

As it turns out, the ruse my dad got roped into — a variation of imposter scam — is the most common form of fraud in the United States.

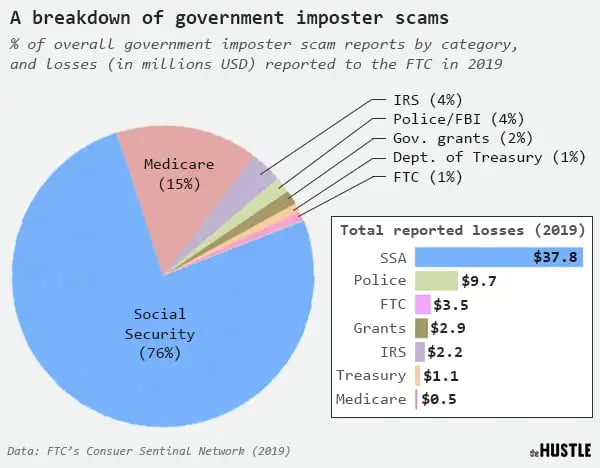

In 2019, 1.7m Americans were ensnared in some form of fraud, according to data from the Federal Trade Commission. Of those reports, 648k were imposter scams, collectively totaling $610.8m in losses to consumers. Impersonations of government employees accounted for ~60% of these cases.

About 5% of people who get one of these calls end up losing money. And at $1,100, the median loss is no small sum for most Americans.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

The scam generally works like so:

- A large team of individuals (usually at a call center in India) obtain contact information from data brokers.

- Using publicly available information on government agencies, they write an elaborate script, often using real names and facts pulled from actual cases.

- They use caller ID spoofing to mirror real government phone numbers.

- They convince a victim to buy gift cards at a popular big-box retailer like Target, Walmart, or CVS.

- Once the scammers obtain gift card numbers from a victim, they transfer them to a group of US-based “runners,” who liquidate and launder the funds — either by buying resellable goods at the store or selling them via gift card resale sites. Some even have their own gift card resale apps.

These scammers go after everyone: teenage retail workers, suburban moms, octogenarian Stanford professors. The elderly (65+) tend to get hit the hardest, losing an average of $1.5k per incident; some get taken for six figures.

The perpetrators are highly skilled and elusive. But several DOJ cases from recent years shed light on the enormity of their operations:

- 24 individuals in the US and India were charged in relation to a $73m IRS impersonation scam perpetrated between 2012 and 2016.

- 15 individuals in the US and India were charged with scamming 2k people out of $5.5m in 2018.

- 61 individuals in the US and India were charged for a scam involving tens of thousands of people out of hundreds of millions of dollars in 2016.

“This is a situation where the scammer uses what they know about the federal government to impersonate a trusted source and catch you off guard,” Patti Poss, an attorney in the FTC’s consumer protection bureau, told The Hustle.

In the last 18 months, fake Social Security calls have become the No. 1 scam in the country, bilking 180k Americans — including my dad — out of more than $40m.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

My dad had received robocalls in the past and ignored them. But this one was different: it was a real, authoritative person on the line who knew his full name and address.

After “Agent David White” paralyzed my dad with fear, he set out to establish a line of trust using an intricate web of details.

He provided a case number (CFMA020034) and a call-back number in case they were disconnected, then transferred my dad to two other men claiming to be special agents: Kyle Williamson (ID #437409) and Preston Grubbs (ID #US10319).

The names the scammers used were real — Williamson is currently the special agent in charge of the El Paso DEA; Grubbs is the federal organization’s principal deputy administrator — and the phone number mirrored the actual El Paso DEA office line. (A rep from the El Paso DEA office told me they are aware of the impersonations.)

“Grubbs” assured my dad that he didn’t believe he was responsible for the crimes, and that his SSN had been compromised. Even so, they’d have to suspend his number, which would “freeze his bank account for 9 years” and jeopardize his retirement savings.

According to Grubbs, there was only one way out: my dad had to convert the money to “government certified gift vouchers,” or gift cards.

The gift card run-around

In recent years, gift cards have become the scammer’s payment method du jour.

Last year, gift cards accounted for $102.9m in payments that victims made to scammers, and were requested in 4 out of 5 imposter scams. The reasons for this are simple: 1) They ensure anonymity, 2) They can be liquidated quickly, and 3) Once they are used, it’s nearly impossible to recoup lost funds.

“These cards are like cash,” Poss, the FTC lawyer, told me. “Once they’re gone, it’s very difficult to get your money back or trace who used them.”

$3,000 worth of Target gift cards purchased by my dad, per the scammer’s orders (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

My dad was instructed to go to Target — a popular destination for scammers — and purchase gift cards. He wasn’t to speak to anyone about the “investigation” and was to keep his phone on at all times.

He protested that he had cancer and couldn’t go to stores as a high-risk individual during a pandemic. But the scammer “worked on [his] emotional vulnerability” and reiterated that his account would be frozen if he didn’t comply.

So, my dad found himself standing in line at Target, beading with sweat, flip phone on speaker in his pocket, buying two $500 gift cards.

In a statement later provided to me, a Target communications employee maintained that the company takes a “multi-layered, comprehensive approach to preventing theft and fraud that includes partnerships with local authorities, technology, and team member training.”

Recently, Target imposed a gift card limit of $1,030 per store, per customer. They also now place signage in their stores (and on their website) warning customers of fraud.

A placard by the gift cards at a Target store warns shoppers of scams (via reddit u/por_que_tacos)

But a common complaint among people who fall victim to gift card scams is that the stores’ prevention and education methods often fall short.

My dad was assisted by two Target employees, neither of whom questioned his purchase or informed him of ongoing scams. An hour later, the scammer (who he was still on the phone with) persuaded him to go to a nearby Safeway supermarket to buy another $2k in Target gift cards. He complied.

Sitting in a hot car in a parking lot, my dad scratched off the back of the gift cards and read the codes over the phone.

By this point, my dad had been on the phone for 4 hours and had spent $3k. “Grubbs” said it was getting late and my dad should go home and eat some dinner.

“You’ve had a stressful day,” he said. “Go relax and I’ll follow up with you in the morning.”

Why we fall for scams

There’s still something I can’t shake: how could my dad — a highly intelligent, cautious person — fall for something that sounds like a bad movie script?

The answers lie in the social psychology of persuasion.

In attempting to persuade another person to do something — fall for a scam, buy a product, win an argument — an individual typically takes one of two routes that mirror Aristotle’s artistic proofs:

- A central route to persuasion that employs logic and critical thinking.

- A peripheral route to persuasion that preys on emotion and employs “mental shortcuts to bypass logical argument.”

Scammers use the latter of the two, often starting the conversation off with a series of accusations that invoke panic and fear.

“These surges of strong emotion serve to interfere with the victim’s ability to call on his or her capacity for logical thinking, such as his capacity for counterargument,” writes Jonathan Rusch, a legal scholar who spent 27 years working on fraud cases at the DOJ.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Once the scammer has paralyzed a victim with fear, he will offer up a solution to the nonexistent problem he invented. After being threatened with criminal charges and potential bankruptcy, a few thousand dollars in gift cards seems more palatable.

A scammer will also constantly remind a victim of his authority, and endorse it with supplementary details.

In his book Influence, the social psychologist Robert Cialdini cites a study in which 22 nurses received a call from a “doctor,” ordering a specific dosage of medicine to be administered to a patient. In 95% of the cases, the nurse compiled without verifying the caller’s identity — simply because the caller spoke so authoritatively about medicine.

Of course, the call my dad received was peppered with red flags and nonsense. But his logical faculties didn’t return until it was too late.

“It was a form of mind control,” my dad told me, a few days after the incident. “I became emotionally involved, and once my fear took over I no longer had the ability to see or think rationally. It’s as if someone else or something else occupied my body and mind for four hours, almost like something you might experience in a bad dream.”

Moments after he hung up, he did a little Googling and realized he’d been “suckered.” He filed a report with the FTC and the local police department. I also immediately called Target to cancel the cards, but the store claimed the cards had already been redeemed.

(I later learned that 4 of the 6 cards weren’t redeemed until the following morning, which means Target could have taken action. As of 7/5, my dad currently has an open case with their gift card fraud department).

The monetary loss is significant. But the hardest thing for my dad to swallow has been his pride.

Two weeks later, he’s dealing with the emotional fall-out of the scam: anxiety, embarrassment, grief, anger. He’s considering joining a “scambaiting” forum like 419 Eater, where posters — many of whom are fraud victims — try to get some form of vigilante justice by badgering scammers.

“I want to call back and say, ‘This is the DOJ,’” he recently fantasized, over a beer. “‘We traced your call and we got you, motherfucker!’”

Federal agencies will never call you on the phone to tell you you’re in trouble (Creative Commons)

In the wake of this ordeal, my dad and I have spent hours on the phone with the FTC, the police, and Target’s fraud team. In the process, we gleaned a few tips for avoiding government imposter scams:

- Government agencies will never call you out of the blue to tell you you’re in trouble. They’ll send a letter in the mail.

- Caller ID should not be trusted — even when a phone number appears to be official or recognizable.

- You should always check with the real agency by calling the number(s) listed on their official websites.

- Never pay someone claiming to be a government official with a gift card or wire transfer.

If you do fall victim to a gift card scam, immediately call the store where it was purchased — they might be able to cancel it in time. You should also file a complaint with the FTC here and call your local police department to report the crime.