On a warm night in May of 1969, a throng of awestruck gamblers crowded around a well-worn roulette table in the Italian Riviera.

At the center stood a gangly 38-year-old medical professor in a rumpled suit. He’d just placed a $100,000 bet ($715,000 in 2019 dollars) on a single spin of the wheel. As the croupier unleashed the little white ball, the room went silent. He couldn’t possibly be this lucky… could he?

But Dr. Richard Jarecki wasn’t leaving it up to chance. He’d spent thousands of hours devising an ingenious method of winning — and it would soon net him the modern equivalent of more than $8,000,000.

From Nazi Germany to New Jersey

Born in 1931 to a Jewish family in Stettin, Germany, Richard Jarecki was thrust into a world in chaos.

Germany was in the throes of economic hardship, and the Nazi Party was gaining support with an anti-Semitic platform that blamed the country’s ills on Jewish citizens. Jarecki’s parents, a dermatologist and a shipping industry heiress, were gradually stripped of everything they had. Facing internment at the onset of WWII, they fled to America for a better life.

In New Jersey, the young Jarecki found solace in games like rummy, skat, and bridge, and took great pleasure in “habitually winning money” from friends. Gifted with a brilliant mind that could retain numbers and statistics, he went to study medicine — a noble pursuit that pleased his father.

As a young man in the ‘50s, Jarecki gained a reputation as one of the world’s foremost medical researchers.

But he harbored a secret: His true passion lay in the dark, musty halls of casinos.

The strategy

Sometime around 1960, Jarecki developed an obsession with roulette, a game where a little ball is spun around a randomly numbered, multi-colored wheel and the player places bets on where it will land.

Though roulette was considered by many to be purely a game of chance, Jarecki was convinced that it could be “beat.”

He noticed that at the end of each night, casinos would replace cards and dice with fresh sets — but the expensive roulette wheels went untouched and often stayed in service for decades before being replaced.

Like any other machine, these wheels acquired wear and tear. Jarecki began to suspect that tiny defects — chips, dents, scratches, unlevel surfaces — might cause certain wheels to land on certain numbers more frequently than randomocity prescribed.

A roulette wheel Jarecki played on in the ‘60s (Thüringer, Roulette-Forum)

The doctor spent weekends commuting between the operating table and the roulette table, manually recording thousands upon thousands of spins, and analyzing the data for statistical abnormalities.

“I [experimented] until I had a rough outline of a system based on the previous winning numbers,” he told the Sydney Morning Herald in 1969. “If numbers 1, 2, and 3 won the last 3 rounds, [I could determine] what was most likely to win the next 3.”

Jarecki’s approach wasn’t new: Joseph Jagger, thought to be the “pioneer” of the so-called “biased wheel” strategy, had won hefty sums this way in the 1880s. In 1947, researchers Albert Hibbs and Dr. Roy Walford used the technique to buy a yacht and sail off into the Caribbean sunset. Then, there was Helmut Berlin, an ex-lathe operator who, in 1950, hired a team of cronies to track wheels and made off with $420,000.

But for Jarecki, it wasn’t about the money: He wanted to perfect the system, repeat it, and “beat” the wheel. It was a matter of man triumphing over machine.

After months of collecting data, he scraped together $100 (his rainy day savings) and hit the casino. He’d never gambled — and though he trusted his research, he knew he was still up against “the element of chance.”

In a matter of hours, he flipped his $100 into $5,000 (~$41,000 today). And with this validation, he turned to much higher stakes.

Breaking the odds

In the mid-60s, Jarecki moved to Germany and took up a post at the University of Heidelberg to study electrophoresis and forensic medicine.

He’d recently won a highly prestigious peace prize (one of only 12 awarded worldwide) for his work on international cooperation in medicine, and, as a result, had gained entry into an elite group of doctors and scientists.

But Jarecki had his eyes on a different prize: The nearby casinos.

Jarecki (center) draws a crowd at a casino in Europe (Jarecki family archive, via NYT)

European roulette wheels offered better odds than American wheels: They had 37 slots instead of 38, reducing the casino’s edge over the player from 5.26% to 2.7%. And, as Jarecki would discover, they were just his type of machine — old, janky, and full of physical defects.

With his wife, Carol, he scouted dozens of wheels at casinos around Europe, from Monte Carlo (Monaco), to Divonne-les-Bains (France), to Baden-Baden (Germany). The pair recruited a team of 8 “clockers” who posted up at these venues, sometimes recording as many as 20,000 spins over a month-long period.

Then, in 1964, he made his first strike.

After establishing which wheels were biased, he secured a £25,000 loan from a Swiss financier and spent 6 months candidly exacting his strategy. By the end of the run, he’d netted £625,000 (roughly $6,700,000 today).

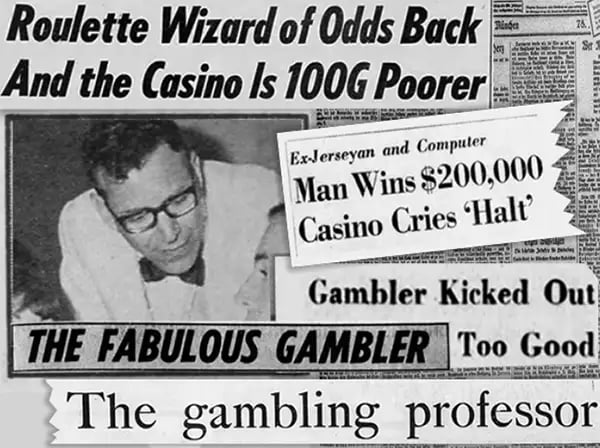

Jarecki’s victories made headlines in newspapers all over the world, from Kansas to Australia. Everyone wanted his “secret” — but he knew that if he wanted to replicate the feat, he’d have to conceal his true methodology.

Jarecki made international news in the ‘60s (via various newspaper archives)

So, he concocted a “fanciful tale” for the press: He tallied roulette outcomes daily, then fed the information into an Atlas supercomputer, which told him which numbers to pick.

At the time, wrote gambling historian, Russell Barnhart, in Beating the Wheel, “Computers were looked upon as creatures from outer space… Few persons, including casino managers, were vocationally qualified to distinguish myth from reality.”

Hiding behind this technological ruse, Jarecki continued to keep tabs on biased tables — and prepare for his next big move.

A casino owner’s worst nightmare

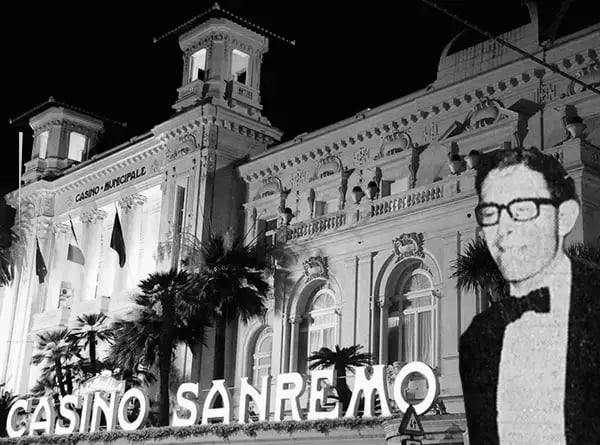

Flush with cash, Jarecki purchased a luxury apartment near San Remo, a palatial Italian casino on the shores of the Mediterranean.

Through studious observation, he identified a table that had a habit of landing on #33 far more than usual — a result of the “constant friction of the ball against the wheel.”

On a spring night in 1968, he drove his white Rolls Royce to the gambling den and, over 3 days, proceeded to win $48,000 ($360,000 today).

Eight months later he returned, winning $192,000 ($1,400,000) in a single weekend, and breaking the bank (depleting the casino’s on-hand cash) at two different wheels twice in one night. Teetering on bankruptcy, the casino owner had no option but to issue Jarecki a 15-day ban… for “being too good.”

The night the ban was lifted, Jarecki returned and won another $100,000 ($717,000) — so much money that the casino had to give him a promissory note.

When Jarecki showed up to a casino, large crowds would gather to witness the master at work. Many would mirror his every move, placing small bets on the same numbers.

In a bid to outfox Jarecki, casino owners rearranged his favorite roulette wheels in different spots every night. But the professor knew every vein in the wood — every nic, crack, scratch, and discoloration — and he always ferreted them out.

“He is a menace to every casino in Europe,” casino owner, Signor Lardera, told the Sydney Morning Herald. “I don’t know how he does it exactly, but if he never returned to my casino I would be a very happy man.”

“If the casino directors don’t like to lose,” retorted Jarecki, “they should sell vegetables.”

Eventually, San Remo gave up and replaced all 24 of its roulette wheels at a steep cost to the house. It was, they ceded, the only way to stop the best player they’d ever seen.

In the decades following Jarecki’s dominance, casinos invested heavily in monitoring their roulette tables for defects and building wheels less prone to bias. Today, most wheels have gone digital, run by algorithms programmed to favor the house.

Roulette to the grave

All told, Jarecki made a reported $1,250,000 ($8,000,000 today) placing hefty bets on biased roulette tables between 1964 and 1969.

The Italian newspaper Il Giorno called him “The world’s most successful roulette player” — a reedy academic who “[didn’t] look like a gambler.” Once deemed to be an “egghead” on campus, he became “the hero of every student at his university.”

In 1973, Jarecki moved his family back to New Jersey, where he started a new career as a commodities broker. With the help of his billionaire brother, he multiplied his fortune 10 times over. He also passed down his penchant for games to his son, who, at the age of 9, became the youngest chess master in history.

On occasion, casino owners would call him with partnership offers, but he never took the bait: “He [liked] to take money from the casinos,” his wife, Carol, told TheNew York Times, “not give it to them.”

In the early ‘90s, Jarecki grew tired of Atlantic City and relocated to Manila, home to a flourishing (and loosely regulated) gambling scene. He remained there until his death in 2018, at the age of 87.

Tucked in the corner of a bustling gambling hall, surrounded by neon lights and slot machines, he wagered his final bet. The wheel spun round and round. Like so many times before, the little white ball landed on his number.