Dan Brown did everything an inventor should do.

He identified a need in the market. He spent years painstakingly iterating his design. He invested in good prototypes. And most importantly, he secured patents.

His product, the Bionic Wrench, was a tool enthusiast’s wet dream — the type of Father’s Day gift that made dads mutter “Holy guacamole” and bashfully adjust their baseball caps. When it debuted in 2005, it flew off shelves and racked up a trophy case of design awards.

But Brown would soon learn a difficult lesson: sometimes, a product is so good that a multinational corporation can’t keep their hands off of it.

This is the story of a small business owner who got trampled on by “America’s Most Trusted Tool Brand” — and, against insurmountable odds, decided to fight back.

One wrench to rule them all

Born to a blue-collar family in the Southside of Chicago, Dan Brown spent his summers “fixing things.” If it was broken, he found a way to make it work again.

He was the first in his family’s history to graduate from college, and parlayed his handiness into an successful career in engineering and design.

On a Summer day in 2002, Brown’s son was trying to remove a few stubborn bolts on a lawnmower. Instead of reaching for a wrench, he grabbed the pliers.

“It was a user expressing a basic need,” recalls Brown. “And I thought, there’s got to be a better way to make a wrench so that people actually want to use it.”

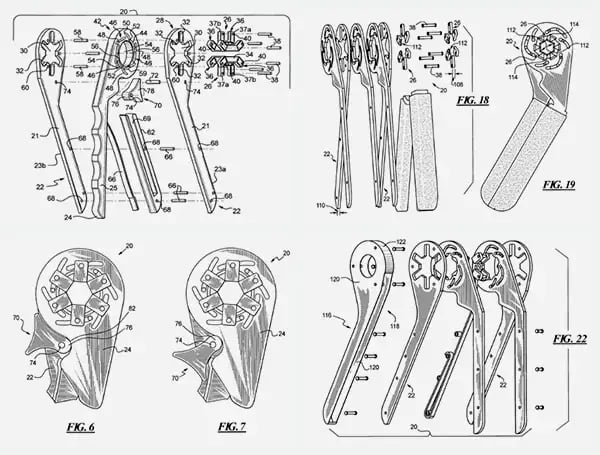

Over the next 3 years, Brown became obsessed with redesigning the age-old hand-tool. He crafted dozens of prototypes, put in hundreds of hours of “engineering sweat equity,” and spent tens of thousands of dollars on patents, trademarks, and copyrights.

In 2005, he formed a company, LoggerHead Tools, and debuted the “Bionic Wrench.”

In an inhospitable tool market, where 6 out of every 7 concepts fail, the Bionic Wrench was a unicorn: it won Popular Mechanics’ product of the year, sold 10k units on QVC in a matter of minutes, and piqued the interest of retailers around the country.

Launching the venture cost Brown nearly $500k in intellectual property protection — and to fund it, he had to cash in his retirement fund and bring in two partners.

“I thought if I did things the right way and got the patents, I’d have the right to a 20-year monopoly on my product, and could recoup my investment,” he says. “But that’s not what happened…”

Sears happened

Brown had a mission to keep his manufacturing in America — and to compensate for the higher cost of labor, he realized he needed to sell a higher volume of product.

When Sears came knocking, he saw the perfect opportunity to work with a “reliable partner that wouldn’t screw [him].”

Between 2009 and 2011, Sears and Brown shared a symbiotic relationship: the retailer placed increasingly large orders of the Bionic Wrench — 15k, 75k, 300k units — and sold out each time. Soon, it was the chain’s best-selling and most profitable tool, far outpacing the company’s own Craftsman products.

Then, that relationship began to sour.

Sears had initially agreed to place 300k units for 2012, but by mid year, they inexplicably revised the order to less than 3k units — 1% of what they’d agreed on. As the months passed, the company started to evade Brown’s emails.

“I asked for reasons, and they just give me excuse and after excuse,” says Brown. “Then, they went dark.”

It wasn’t long before Brown found out the gut-wrenching reason why.

Under its Craftsman brand, Sears had introduced the “Max Axess Locking Wrench” — a tool that bore a shocking resemblance to the Bionic Wrench, but was manufactured in China and sold for less than half the price.

Brown had been knocked off.

Dan v. Goliath

Everything Brown had worked for was on the line; he wasn’t going down without a fight.

He secured a lawyer and, in 2013, filed a suit against Sears and their manufacturer, Apex, alleging that they had willfully infringed on two Bionic Wrench patents (here and here).

For 4 years, the proceedings inched through the legal system. Sears and Apex balked, stalled, and delayed every step of the way, hoping to exhaust Brown’s defense.

The consequences for Brown were tremendous: his sales crumbled, his Pennsylvania-based manufacturer was forced to lay of 30 workers, and his direct litigation costs crept past $1m.

Against all odds, something miraculous happened: Brown won.

In July of 2017, a jury found that Sears and Apex had willfully infringed LoggerHead’s patents, and awarded Brown $6m in damages.

But it wasn’t over: 5 months later, in December, Sears and Apex appealed, and a judge ruled the case a mistrial on the grounds that certain terms in the patent claims had been “incorrect.” It was a technicality — and it sent LoggerHead back to ground zero.

How to legally steal a product

In the corporate world, there is a concept called “efficient infringement,” or, as Brown likes to call it, the “Piracy Business Model.”

Companies like Sears have found that it’s cheaper to steal a patented product and face the legal repercussions than is it to license it, or invest in their own innovation. They know that most small businesses (their favorite prey) can’t afford the $2-4m required to take a case to a district court.

“Multinational companies like Sears know that screwing over their suppliers is easy money,” says Mike Collins, an author who has studied manufacturing for 30 years. “You see it time and time again.”

Sears seems to have a special knack for it.

Dating back to 1960, there are multiple instances of the retailer ripping off other patented wrenches. In one case, it took two decades for the inventor to get compensated. More recently, in 2004, Sears copied a drywall-cutting tool and had to pay out a $25m settlement.

We reached out to Sears on this history, and they merely redirected us to court transcripts; Sears’ manufacturer, Apex (now owned by Bain Capital) did not respond to our request for comment.

![]()

Today, Dan Brown and his son, Dan Brown, Jr., continue to make the Bionic Wrench and a line of other tools, but things aren’t what they were before. Other retailers are aware of the ongoing legal case, and are wary to partner with him.

“It’s like doing business with a black cloud over your head,” Brown tells us. “But I always come back to something my mother told me: if you don’t fight, you lose by default.”

His nemesis hasn’t faired much better: once the “king of retailers,” Sears is now cash-starved and on the brink of survival. The corporation’s own industry has been co-opted by e-commerce titans, and in the time since the trial began, their stock has plummeted from $40 to $3 per share.

In other words, they’re a rusty artifact, rife with loose nuts and bolts — just the job for a Bionic Wrench.

Note: If you’re interested in reading more about this case, check out these documents:

Bionic Wrench patents (1, 2); LoggerHead’s official complaint for patent infringement (2013); Another complaint filed by LoggerHead (2013); Mistrial ruling (2017); A video tour of LoggerHead’s manufacturing facility