Last month, 19-year-old Santiago Lopez became the first person to earn $1m US as an “ethical” hacker.

Santiago — who had never even heard of hacking until just a few years ago — first became interested in computing when he stumbled across a B-list movie called Hackers on late night TV as a kid.

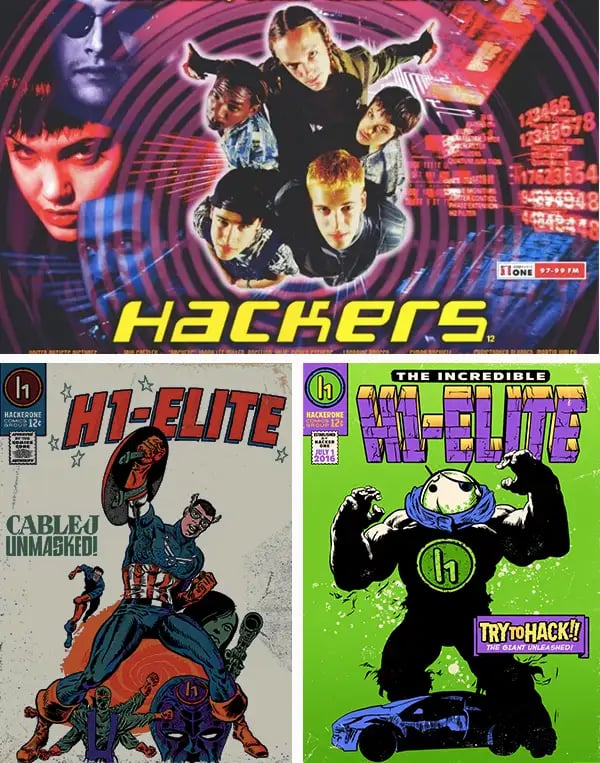

In the film, a hacker prodigy crashes the the New York Stock Exchange and teams up with a pink-haired cyber-sidekick to outsmart an evil genius named Cereal Killer.

Hackers lost millions at the box office when it came out in 1995, 5 years before Santiago was born. Print newspaper critics were ruthless, writing: “Falls flatter than a floppy disk;” “It sums up the worst of the internet era.”

But to Santiago and thousands of other kids who watched the film, Hackers wasn’t a fear-mongering sci-fi flick: It was a challenge.

Today, Santiago is the most successful professional hacker in the world. In his 4-year-long career, he’s exploited 1,748 vulnerabilities — and last year, his skills earned him more than 40x Argentina’s annual median salary.

Santiago Lopez in a recent interview with the BBC (via BBC)

In the not-too-distant past, hackers lived in the shadows and kept their digital exploits to themselves. But today’s elite young hackers are high-profile public figures: Accompanied by parental chaperones, they travel internationally to participate in hackathons and give keynote speeches at cybersecurity conferences.

Where hackers were once pursued by authorities, these kids are pursued by elite universities; where hackers once got jail time, these kids get job offers.

Where did these kids come from? And how did a scattered community of quasi-criminals evolve into a corps of high-achievers hell-bent on saving the world?

White hats are finally fashionable

To understand the hackers, you first need to understand their hats.

We’re not talking about wardrobes here. All hackers use the same set of tools — computers and code — to solve technical problems. But not all hackers approach technical problems with the same set of ethics.

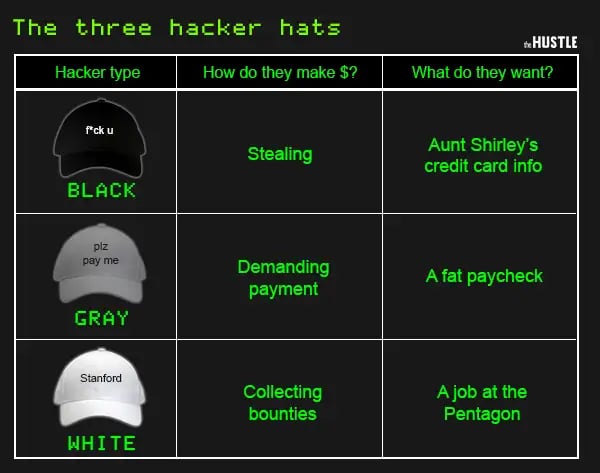

Hackers exist on an ethical spectrum. On one end, “black hat” hackers find vulnerabilities to rob unsuspecting victims; on the other, “white hat” hackers find vulnerabilities to keep clients secure. “Gray hat” hackers do a little bit of both, finding vulnerabilities without being asked and then seeking payment.

Visual: The Hustle

For most of hacking’s history, white hat hacking opportunities were few and hard to find.

Some computing companies offered bounties to their employees in the 1990’s and 2000’s (Netscape launched a program in 1995), popular media portrayed hackers as dangerous rogues, and most companies would never have considered “hiring” hackers.

Without many ethical hacking opportunities, there were few ethical hackers.

But in 2010, Google launched a public bug bounty program. The next year, Facebook rolled out a similar program, offering white hat hackers a minimum of $500 and eliminating the limit to the amount they could earn.

Across the internet, hackers took notice: The world’s biggest companies had started offering hackers a legal way to make big money.

But the amount of opportunity for white hat hackers really took off when third-party companies started launching bug bounty platforms, which cataloged all of the internet’s high-paying hacks in organized directories.

All of a sudden, hacking became an accessible, rewarding option for anyone with a computer — and middle school teachers, Fortune 500 CEOs, and national defense officials all wanted kids to start white hat hacking.

A rolodex for ethical hackers

The world’s most valuable digital directory for white hat hackers lives on the 12th floor of an old bank building in San Francisco, at the headquarters of a company called HackerOne.

HackerOne’s bug bounty program is the largest hacker brokerage on the internet: It gives hackers a directory of companies they’re allowed to exploit, and it gives companies access to ethical hackers who will continuously secure their businesses.

HackerOne was founded by Jobert Abma and Michiel Prins, 2 Dutch hackers who had found personal success as gray hats but who found the process exhausting and inefficient.

Jobert Abma, co-founder of the bug bounty platform HackerOne (via Business Insider)

“We started noticing some downsides to the whole model because of the way we reported,” Jobert told me on a recent visit to their San Francisco headquarters. “Some companies didn’t care about what we actually found over time.”

So, after noticing companies offering official white hat programs, Abma and Prins dreamt up a transparent platform that would match hackers with bugs, incentivizing clients to join the (relatively) cheap platform and incentivizing hackers to continue hunting for new vulnerabilities.

Most importantly, their platform would allow hackers to browse a number of different bugs in one place instead of having to monitor dozens of company-specific programs.

In 2012 — the year after Facebook formalized its bug bounty program — Abma and Prins launched HackerOne.

Today, 300k hackers from 150 countries use HackerOne’s platform to earn money as white hat hackers.

HackerOne has several competitors (including BugCrowd and HackenProof), but as the oldest and largest bug bounty platform, HackerOne has outsized influence.

When Facebook and Microsoft teamed up to organize an open-source bug bounty coalition called Internet Bug Bounty (IBB), they tapped Hackerone’s co-founder to help run it: Today, HackerOne sponsors the IBB alongside Facebook, Microsoft, GitHub, and the Ford Foundation

By building a directory of ethical hacking opportunities, HackerOne has opened the floodgates for big business: On a scale that was never before possible, hackers across the world could hack companies like Google, Twitter, Spotify, Snapchat, Coinbase, Alibaba, Goldman Sachs, Toyota, IBM, Uber — and get paid, not prosecuted.

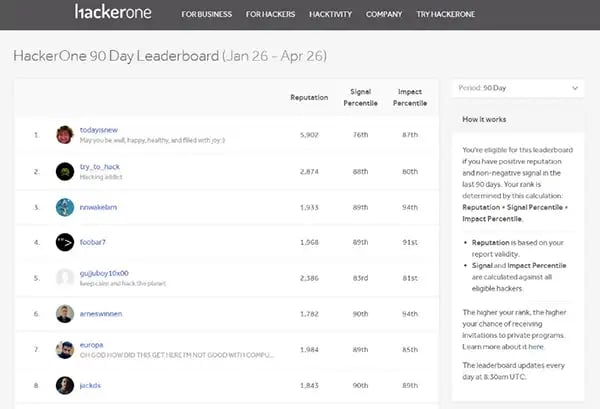

HackerOne organizes its platform much like a video game, offering eager hackers missions in a directory of “new hackable targets” and listing the most successful hackers in an online leaderboard.

Santiago, who is known by the alias “try_to_hack,” is #2 on HackerOne’s leaderboard — a position that has earned him more than $1m.

Santiago, AKA “try_to_hack,” is #2 on HackerOne’s leaderboard (via HackerOne)

Meet the young hacker professionals

Last year alone, hackers earned $19m on HackerOne. Although less than 1% of the hackers on the platform make a full-time living on HackerOne, top earners like Santiago earn hundreds of thousands of dollars each year.

Santiago is just one member of a new generation of young professional hackers focused on fixing the internet — not breaking it. His peers are no less impressive:

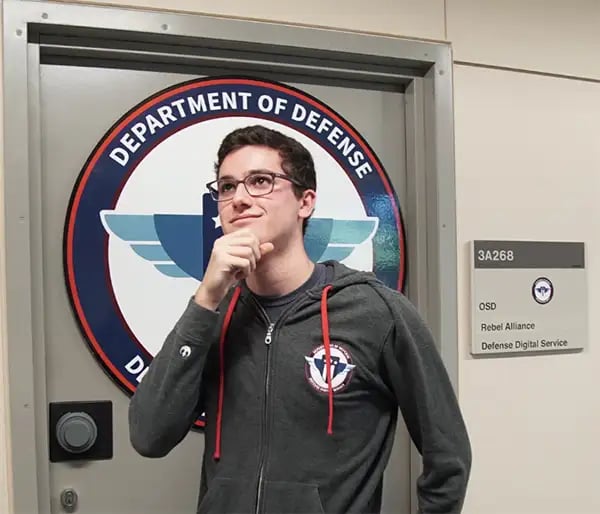

- Jack Cable, 18, hacked into (and subsequently interned at) the Pentagon, started 2 companies, and earned enough hacker-cash to pay tuition at Stanford.

- Paul Vann, 17, runs a cybersecurity consultancy called VannTech Cyber and tracks down Ukrainian cybercriminals in his spare time. He plans to attend MIT.

- CyFi, 18, founded a non-profit called r00tz asylum to educate other young hackers. She goes by a pseudonym to protect her privacy.

Bug bounty platforms are specifically focused on attracting young people like these productive prodigies.

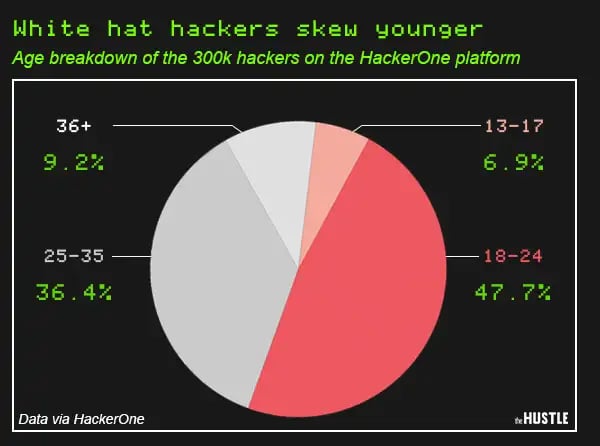

So far, their efforts seem to be paying off: According to a recent HackerOne survey: 57% of millenials saw hacking as a legitimate professional path, compared to just 31% of people over the age of 35.

The age breakdown of the 300k hackers on the HackerOne platform (data via HackerOne; visual by The Hustle)

Many of these hacker high-achievers wouldn’t have even gotten into hacking if it weren’t for bug bounty platforms like HackerOne.

“I wouldn’t even be doing security without bug bounty programs,” Cable told me.

Bright, ambitious kids like Santiago and Cable simply have too much to lose to mess in the murky waters of gray hat hacking. But bug bounty platforms offer high-achieving kids like Santiago and Cable opportunities to make money, pad their resumes, and gain valuable job experience.

But it’s a 2-way street: White hat hackers need bug bounty platforms, but bug bounty platforms also need hackers to provide value to their clients. HackerOne makes money by charging clients subscription fees for access to its talented hackers: Hackers like Santiago and Cable are their product.

To ensure they have a steady supply of hacker talent, HackerOne and other bug bounty programs are investing in the next generation of hackers.

Building the prodigy pipeline

HackerOne offers a series of free videos that teach kids how to hack called Hacker101 and an e-book Webhacking101: How to Make Money Hacking Ethically to get kids interested in white hat hacking and, one day, join HackerOne’s platform.

Hackers start young. Entrepreneurs have a “30 Under 30;” hackers have a “15 Under 15” (that’s not a joke — CyFi and Paul Vann, and were members of CSMonitor’s inaugural roster).

CyFi, the pseudonymous teenage hacker behind the hacker education non-profit r00tz, wears glasses for privacy (via Wired)

Kristoffer Von Hassel, an 11 year old included in the 15 Under 15, is considered the youngest professional hacker in the world. At 5, Von Hassel says he “hacked into the XBox One,” because he was “desperate to get into games [he] weren’t allowed to play.”

After hacking into his XBox, Von Hassel’s dad (a computer systems engineer) sat him down and explained bug ethics. He presented his son with two options: Tell people about the bug on YouTube so everyone knows, or tell Microsoft, so they can fix it.

Von Hassel chose to tell Microsoft.

This is exactly the kind of kid HackerOne wants on its platform: A young, ethical hacker with nowhere to go up. By expanding educational resources for young kids to learn about white hat hacking, HackerOne hopes to manufacture many more Von Hassels.

The new hacker economy

The white hat hacker revolution extends far beyond bug bounty platforms: A whole secondary economy has emerged to cater to these budding ethical hackers. Across the country, new companies train, evaluate, and hire talented young hackers.

Hack Club offers a nationwide network of after-school programs meant to get kids interested in hacking. The Department of Defense sponsors hacking competitions to get kids interested in national defense. A student hackathon league called Major League Hacking (MLH) helps students prepare for jobs that involve hacking.

The flurry of hacktivity has also reshaped job market. Hacker-specific hiring portals like HackerRank funnel young hackers into tech companies.

Kids like Cable are in high demand. After winning the HackerOne-sponsored “Hack the Pentagon” competition, Jack Cable was recruited for an internship at the Pentagon’s Defense Digital Service (here’s a video of Cable walking through the Pentagon brandishing a lightsaber).

Jack Cable, who “hacked the Pentagon,” at the Department of Defense (via Twitter)

It’s not just teenagers who are impacted, either. To compete with new, hireable hackers like Cable, many career IT professionals are going back to school to become CEHs — “Certified Ethical Hackers.”

The hacker circle of life

The way Jobert Abma sees it, HackerOne doesn’t just offer kids like Santiago and Cable financial opportunity — it provides them with a launchpad for any career they could want.

“Some of our hackers have gotten jobs [with] our customers,” Abma told me. “That’s something that we really encourage, because at the end of the day, that gives them the opportunity to explore not just the technical side of things, but much more than that.”

Indeed, bug bounty programs are just the beginning for successful professional hackers like Santiago and Cable. Companies are lining up to offer them jobs and both of them have saved up enough money to start their own businesses.

Soon, they’ll both move on to new, bigger challenges. At 19, Santiago is getting old for a hacker. As an 18 year old freshman at Stanford, Cable is already so distracted with other options that his bug-bashing days are numbered, too.

But, HackerOne isn’t worried about losing its brightest hackers: That’s just the final piece of the new professional hacker pipeline.

“I think people like Santiago, they’re doing an amazing job because of the talent that they have, but eventually I believe that they will grow tired of it,” Abma told me. “And that’s okay.”

Bug bounty programs aren’t designed to create lifelong hackers; they’re designed to breed cybersecurity success — and by doing that, they will attract the next generation of hungry young hackers.

Passing the torch

The world Santiago glimpsed in Hackers was one where 11-year-olds hacked stock exchanges, hackers named Zero Cool used their hacking skills for good, and clever kids outsmarted the grownups.

At the time, it was laughed out of the box office for a plot that seemed ridiculous. But since when have the crusty old newspaper critics gotten things right?

Today, the world Santiago actually lives in is one where 5-year-olds hack Microsoft, hackers like CyFi launch non-profits, and white hat teens rake in serious cash.

Top: A poster for the 1995 film Hackers (via Movie Poster Shop); Bottom: Jack Cable and Santiago Lopez depicted as comic book superheroes by HackerOne (via HackerOne)

The success of bug bounty platforms like HackerOne and ambitious young hackers like Santiago has convinced most people that hackers can be good.

Now, hacking isn’t just for coders: The Harvard Business Review writes that ‘Hackathons Aren’t just for Coders!’ to encourage middle-managers to think more like hackers. Presidential hopeful Beto O’Rourke was a vocal member of one of America’s most well-known hacker groups.

But while the business of hacking has grown up, the hackers themselves still live and die by the hacker code: Everything is made to be broken and rebuilt. The hackers will become the hacked.

One day soon, Santiago Lopez and Jack Cable will probably launch their own businesses. And when they do, a younger generation of hackers will be waiting to hack them.

All they can do is hope the kids will be wearing the right hats.