Around noon on one of the worst days in the history of Wall Street, Charles E. Mitchell hurried up the steps of the House of Morgan, a two-story gray building across from the New York Stock Exchange.

It was Oct. 24, 1929, and disaster had struck. When the market opened, stocks plummeted so fast the exchange’s ticker tape couldn’t keep up with the frenzy.

The news was particularly dismaying to Mitchell. Renowned as the “ideal modern banking executive,” he had reshaped the very idea of American banking as head of National City Bank and helped fuel the 1920s bull market, which was now in jeopardy.

Inside the House of Morgan, Mitchell and bankers J.P. Morgan Jr., Thomas Lamont, and Albert Wiggin decided to go on a stock-buying spree to inject confidence into investors. The momentum spread at the exchange and, miraculously, the market stabilized.

Mitchell believed the worst had passed.

“I still see nothing to worry about,” he told reporters.

But that day was Black Thursday, and the next week brought Black Monday and Black Tuesday, the defining days of the 1929 stock crash, an event that signaled the beginning of the Great Depression.

A few weeks later, when the smoke cleared enough to assess the damage, several leaders pointed at Mitchell once again. This time, his status as the ideal banker meant he represented something far grimmer.

Senator Carter Glass said later, “He, more than any 50 men, is responsible for this stock crash.”

The rise of a banking celebrity

Most mornings in New York City during the Roaring ’20s, Charles Mitchell could be spotted on the sidewalks of Manhattan on his way to work.

Despite being one of the wealthiest men in New York City, Mitchell walked nearly five miles from his Fifth Avenue mansion to the financial district. His doctor had recommended more fresh air, and the long walks — along with open-water swims — gave him endurance for 12-hour workdays.

A portrait of Charles Mitchell in 1923 (Library of Congress)

This aura of discipline had been part of Mitchell’s persona since his childhood in Chelsea, Massachusetts. In a letter to the local newspaper, he once excoriated his high school’s battalion team for not practicing hard enough.

But Mitchell never questioned his own bona fides. He later characterized a story of how his father bought him a pony — the most privileged gift a child can receive — as a test of his work ethic.

“If you want a pony, you must be its groom,” he recalled his father saying.

In 1916, National City Bank, known today as Citigroup, hired Mitchell to head its new investment banking affiliate, National City Company. City Bank had specialized in commercial banking, mostly for the wealthy, but was then branching into the sale of securities.

The timing coincided with a new era of prosperity for America:

- The creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913 gave people more confidence in the US financial markets.

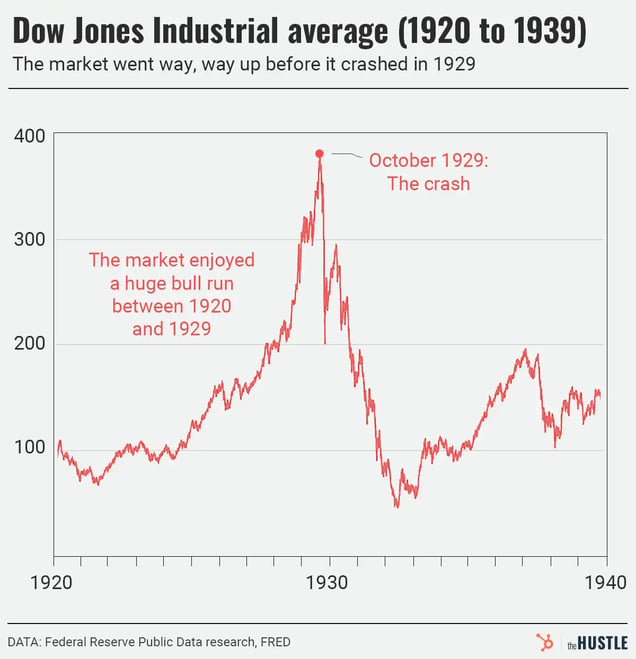

- Buoyed by increases in production and income, Americans started buying more goods and investing. The Dow Jones climbed from under $100 in 1920 to nearly $400 in 1929.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

City Bank didn’t just ride the wave; it created demand.

Mitchell, who was named City’s president in 1921, helped open at least 69 branches in 58 cities, advertising in magazines and on billboards, and dispatching salesmen into churches and train stations to drum up customers.

The visibility made City a top destination for people coming into new money. As one reporter noted at the time, Mitchell turned banks from “frightening places” into “department stores.”

Key to City’s strategy was its combination of commercial and investment banking. Employees at local branches would persuade customers to move money from savings accounts or conservative bonds into exotic securities or City stock, vouching for the safety of the investments.

In the 1920s, the bank sold ~$20B worth of securities, a figure said to be the highest total in the country.

The bounty did wonders for City Bank, which became the nation’s largest bank and saw its stock rise rapidly, and for Mitchell, who bought homes in the Hamptons and Tuxedo Park and amassed a $20m fortune (~$250m today).

His primary residence, an Italian Renaissance-style mansion bordering Central Park, stood five stories tall. He lived there with his family and a staff of 16 live-in help.

President Warren Harding, in a letter to the banker, described the work of Mitchell and City as inspired as much by “patriotic consideration as by motives of enterprise and profit.”

Traders gesture with their hands to trade stocks on Wall Street in New York City, 1925 (Photo by Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

There was no question Mitchell and other investment bankers had inspired the country. Even for people who didn’t invest in the stock market, they stood out as paragons of a new American dream of becoming rich overnight.

Then, all of a sudden, the promise was revealed to be a delusion.

The flaws of the bull market

The foundation of the soaring stock market was built on a couple of questionable strategies propagated by City and other investment banks.

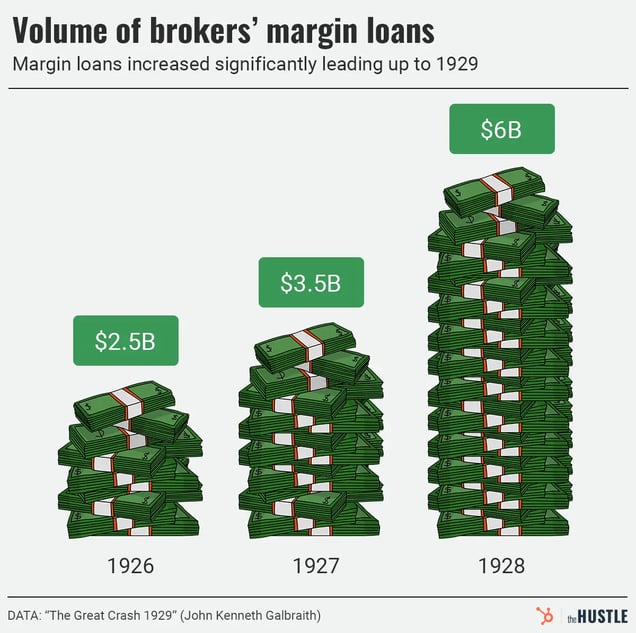

- Margin loans: Many traders bought stocks for ~10% of the cost, borrowing the remaining money with interest from brokers (who represented banks). In the early 1920s, ~$1B was invested on margin annually, according to John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Great Crash 1929, a number that increased to ~$6B in 1928.

- Investment pools: Similar to pump-and-dump schemes, banks held exclusive stock offerings at a low buy-in. They would make the stock available to the general public at a higher price, allowing the bankers and their elite partners to sell their shares for a quick profit.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

These practices continued for years without much controversy.

The pool stocks kept going up, so the people who got in late still saw high returns. And margin investors made more than enough money to pay back their loans — and continue investing — as values increased.

The market would hold together, as long as everyone kept acting like the market would go up forever.

“I often refer to it as the great bullshit market,” Robert McElvaine, a professor at Millsaps College and author of The Great Depression: America 1929-1941, told The Hustle. “Because stocks once bought mainly for their earning power… (were bought) just to sell again as their price goes up.”

Bankers profited wildly.

At City, bonuses increased with the amount of securities sold. From 1927 to 1929, Mitchell made ~$3.4m (~$58m today) outside of his $25k annual salary (~$433k).

And when investors got scared, threatening City’s lifeblood, Mitchell stepped in.

In late March 1929, interest rates on margin loans soared after attempts by the Federal Reserve to rein in margin investing. Amid the panic, Mitchell announced City would provide $25m to shore up the borrowing market. Investors started buying on margin again.

The move helped avert a potential crash. But his actions also helped scuttle growing demands that the country rethink margin investing and allowed speculation to continue into the fall, when Mitchell remained optimistic in spite of teetering stocks.

“There is nothing to worry about in the financial situation in the United States,” he told the New York Times on Oct. 1, preparing to set sail for a four-week European vacation.

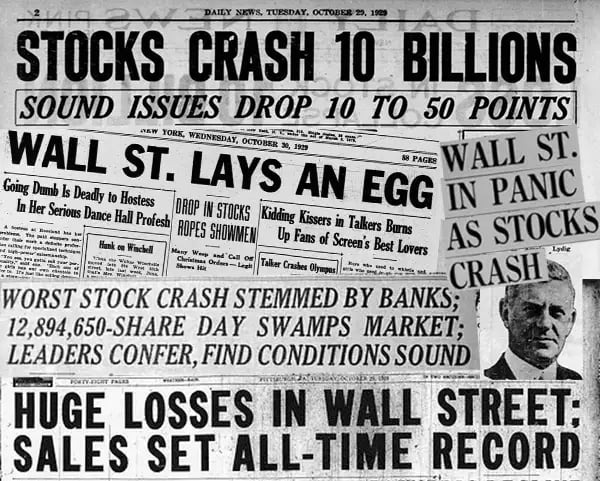

Mitchell’s buying patterns suggest he likely wasn’t trying to deceive. The problem was he happened to be wrong: There was too much speculation, too much borrowing, and when stocks slipped it led to a cascade of margin calls and sell-offs. Some $14B was lost on Black Tuesday alone.

A record sell-off occurred on Black Tuesday, after huge losses the previous several days. (various papers, 1929; Newspapers.com)

Many of the people left holding the bag were those who saw Mitchell and other banking titans as an enlightened class worthy of their trust.

“Every day in the paper, Charlie Mitchell would have something to say, the J.P. Morgan people would have something to say about how good things were,” a broker from the 1920s later explained. “And I thought, ‘Well, they know a lot more about this market than I do.’”

Despite intense scrutiny after the crash, Mitchell knew how to survive. City Bank struggled but didn’t fold, as many banks did. And he made it through one congressional hearing unscathed in 1932.

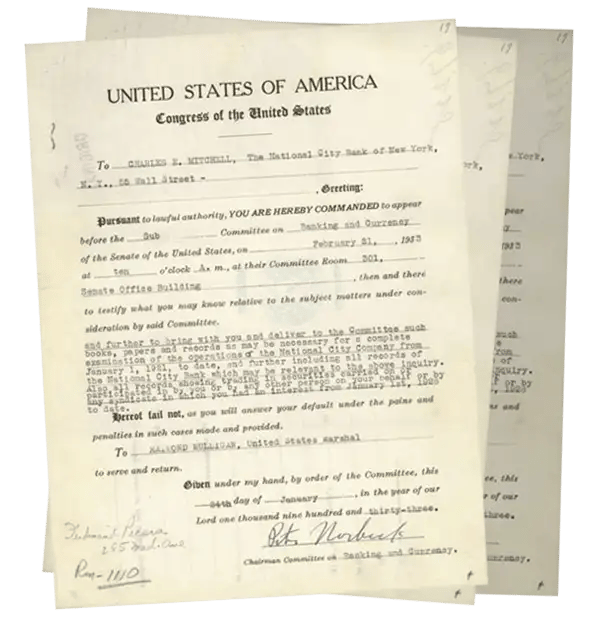

But just as Mitchell prepared for his latest venture in early 1933, a trip to Italy to consult for Benito Mussolini, he received a subpoena. He was due on Capitol Hill one more time.

The exposure of Mitchell and National City Bank

On February 21, Mitchell took a seat in room 301 of the Senate office building, preparing to face a barrage of questions from the Senate Subcommittee on Banking and Currency, helmed by appointed counsel Ferdinand Pecora.

Pecora was no grandstanding politician. He was a cigar-smoking, fedora-wearing New York City prosecutor who liked to call the bank executives “banksters” because he saw them as finance gangsters.

Ferdinand Pecora (1882-1971) looks over documents related to his investigation into the causes of the 1929 Wall Street Crash, 1933 (Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

And Mitchell was his first test.

“(Mitchell) assumed, throughout his testimony, the loftiest moral tone, no matter how questionable the transactions were with respect to which he was interrogated,” Pecora later wrote in his memoir of the hearings.

But Pecora’s questioning quickly led to the banker losing his composure and revealing compromising details.

- Mitchell admitted City Bank was engaged in a practice it “should not be doing” regarding an alleged pool for Anaconda Copper Mining Company stock. In 1929, City sold 1.3m shares of Anaconda Copper at ~$120 a share; the stock eventually plummeted to ~$5.

- Mitchell detailed City Bank’s cross-selling practices. The investment affiliate of City sold up to 40k shares of its own stock in a single day, goosing its price in the late 1920s.

Perhaps most damaging to City — and to other investment bankers — was the revelation that Mitchell and his executives were not the disciplined arbiters they appeared to be. Pecora revealed that City had not properly vetted many of the securities it foisted on customers as safe bets.

“Pecora showed that that was just a lie,” Michael Perino, author of The Hellhound of Wall Street, a book about Pecora and his hearings, told The Hustle.

“The bank was just basically selling anything that came along that they could make money on, and really weren’t telling investors about what their internal investigations had uncovered about the quality of the securities.”

The subpoena the Senate committee used to compel Mitchell to testify (The US Senate)

To some people, notably bankers, Mitchell was a scapegoat. Plenty of other banks had done the same thing. To others, his testimony stood as a potent symbol for the ills of the finance industry and a catalyst for reform:

- The Glass-Steagall Act was signed in 1933, banning banks from acting as both commercial and investment entities, as City had. (The act was repealed in 1999.)

- The 1933 Securities Act required banks to disclose more information on securities they sold.

Mitchell also became a wanted man: Pecora and the senators got him to admit he sold off National City Bank stock to his wife in 1929 to avoid a major tax hit.

A month later, federal authorities showed up to Mitchell’s Fifth Avenue mansion on a Tuesday at 9pm. President Franklin Roosevelt had given his approval for the banker’s arrest on tax evasion.

The aftermath

If you’ve followed the news after America’s other catastrophic financial meltdowns — the financial crisis of 2008, Black Monday in 1987 — you can probably guess what happened to Mitchell.

Basically nothing.

He was acquitted of tax evasion and then sued by the federal government for the same crime. After losing the case, Mitchell fought the decision for several years before settling for an undisclosed sum in 1938.

Mitchell (center) strolls up Broadway surrounded by friends and business associates who are congratulating him on having been declared “not guilty” of two tax evasion charges (Getty Images)

While the testimony damaged his career (Mitchell resigned from City), he was hired as chairman at the investment firm Blyth & Co. in 1935. The stock crash and the legal proceedings put him millions of dollars in debt, but he made a new fortune with Blyth.

Average Americans who put their faith in City Bank didn’t recover so well.

One victim took the stand during the Senate hearings as Mitchell watched from the audience.

Edgar Brown had made ~$100k from selling his theater chain and became a City Bank customer after seeing a magazine advertisement. His goal was financial safety over quick gain, but an employee of City’s investment affiliate convinced him to borrow money and sold him foreign securities and stocks like Anaconda Copper and City Bank.

On Oct. 4, 1929, Brown noticed the market declining and went to a local branch to sell his entire portfolio. But he was “surrounded at once by all the salesmen in the place,” Brown testified, and strong-armed into keeping his securities.

As the afternoon of testimony wrapped up, Pecora asked Brown if he got anything out of the money he entrusted to City.

He gave an answer to which thousands of people who dealt with City Bank and Mitchell could relate: “Not a cent.”

Economy