There’s an old folktale about Jack of the Lantern, an Irishman who tricked the devil twice.

Upon his death, he was barred from both heaven and hell. Doomed to wander the earth for all eternity, a lit coal in a hollowed-out turnip provided his only light.

As an homage to old Jack, Irish and Scottish children would make their own lanterns by carving faces into turnips. In the 1800s, the tradition made its way to America, where celebrants found something much easier to carve than a tough root vegetable: the pumpkin.

Flash forward a few centuries, and pumpkins are a booming business.

Americans are expected to spend a record $10B+ on Halloween items in 2021, up from $8B last year — and pumpkins are a big player: Among the 65% of Americans celebrating Halloween this year, 44% (~94m people) plan to carve one.

While pumpkins can readily be found at most grocery stores, many folks turn to a patch to procure their autumnal canvas.

What are the economics of these orange orbs? And how do pumpkin patches — a largely seasonal enterprise — make money year-round?

To find out, we talked to pumpkin farmers, experts, and patch owners around the country.

From ground to gourd

For a pumpkin farmer, the harvest begins with variety selection — the process of choosing from the hundreds of seeds available each year.

Traditional jack-o’-lanterns are in high demand closer to Halloween. But earlier in the season, customers want decorative pumpkins, like the flat, stackable Cinderella or the warty Marina di Chioggia.

The Hustle

“People have gravitated toward the odd stuff over the years: warts, odd shapes, different colors,” says Mark Craven (no relation to Wes — we asked) of Craven Farm in Snohomish, Washington. “You plant a little bit of everything because you never know what’s going to be hot that year.”

Many growers choose hybrid seeds, a cross between disease-resistant pumpkins and pumpkins that look nice.

These seeds can cost 3-8x more than the standard fare, but improve a farmer’s yield by as much as 30%-50%. For Craven, hybrids are ~$100/1k seeds, but are worth every penny for their color, size, and stem.

Once planted, pumpkins have to contend with myriad natural enemies: insects, weeds, grazing deer, mildew, and, perhaps their biggest threat, weather.

- If it gets too hot, pumpkins can show up in August — way too early for commercial markets.

- If it gets too cold, pumpkins will still be green in October.

If there’s not enough rain, pumpkins may fail to germinate. If there’s too much rain, pumpkins can rot in the soil.

Or they can just float away:

- The Great Pumpkin Flood of 1786 was caused by heavy rains that overflowed the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, sweeping unharvested crops downstream.

- In 1903, it happened again along the Delaware River in Pennsylvania and New York. In a seasonally appropriate move, the water also swept away a local undertaker’s hearse, home, and mortuary.

A flooded pumpkin patch in New Jersey (Wikimedia Commons, via Jackie/Flickr)

Stephen Reiners, a horticulture professor at Cornell AgriTech in New York who works with growers large and small, tells The Hustle that inconsistent weather can also result in fewer bees — a critical contributor to pumpkin production.

“Male flowers produce the pollen, female flowers produce the fruit, but the bees need to transport it,” he explains. Some growers rent beehives for that purpose, which range from $45-$200 per hive.

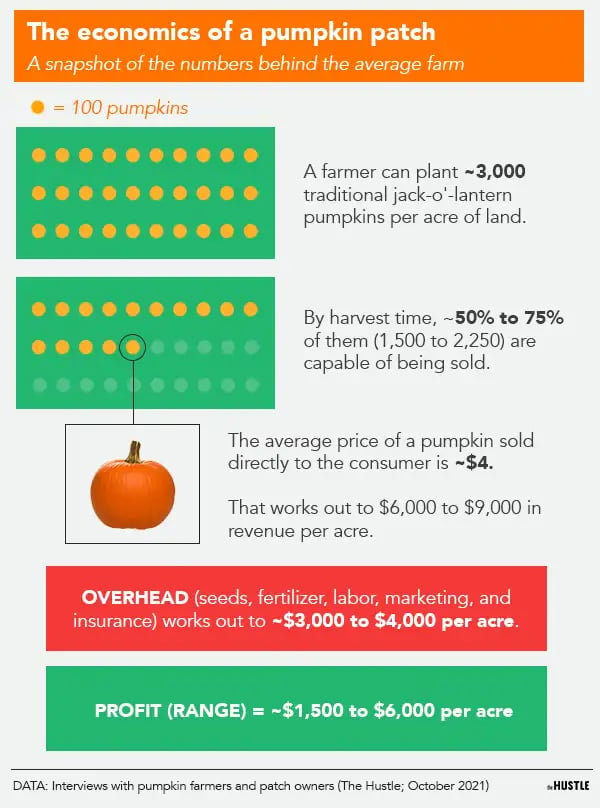

All in, including expenses like seeds fertilizer, labor, marketing, and insurance, Reiners says the typical overhead incurred by a pumpkin farmer might amount to $3k-$4.5k per acre.

But if pumpkins manage to survive this minefield of natural elements, the harvest can be well worth it.

How much is a pumpkin worth?

In 2020, the US produced ~1.4B pounds of pumpkins, sold either: 1) directly to agritourists who visit patches, or 2) wholesale to urban lots and grocery chains.

On the direct sales side, pumpkin patches tend to sell by the pound.

Among a sample of 11 farms across the US compiled by The Hustle, the average per-pound rate was $0.51 — right around $4 for an 8-pound pumpkin.

The economics of these patches might break down like so:

The Hustle

While there are a few farms that run enormous operations, most pumpkin patches range from 2 to 40 acres — enough to yield roughly $12k to $240k in net profit at the higher bounds of our estimates.

The wholesale economics are a little less enticing.

For example, Illinois — which consistently produces the most pumpkins by acreage and weight — credits ~80% of its output to sugar pumpkins (used for pie filling), which are sold wholesale to processors.

Illinois producers usually get $3-$4 per 100 pounds, while other states fluctuate from $11 to $26.50.

Craven no longer sells pumpkins in bulk, but estimates he could get $0.07-$0.10 per pound wholesale — more than 10x less than the average for patch-bought pumpkins.

The Hustle

Craven’s grandparents began farming dairy and berries in 1949. He added pumpkins in 1983, which ultimately took over the bulk of his crop production. Today, he grows 40 acres of pumpkins in a given year, which are priced by size up to $30 for a 50-60 pounder.

He does well for himself — but pumpkin sales are only one part of the equation.

On the weekends, a $22 pass to Craven Farm includes unlimited access to a 15-acre corn maze, hayrides, and minigolf. Other revenue streams include food and coffee stands, and a gift shop.

Craven gets about 20-30k visitors per weekend, often filling up 6 acres of parking — though foot traffic fluctuates depending on the weather and Seahawks games.

Last year, with families desperate for an outdoor activity amid shutdowns, Craven had so many visitors that he ran out of pumpkins for the first time in 38 years.

Bringing the farm to the city

Urban patches — which start with an empty lot in the middle of a dense city — bring the farm closer to home for cosmopolites.

Brandon Helfer, the co-owner of Mr. Jack O’Lanterns Pumpkin Patch, which has a dozen locations in urban areas across California and Florida, buys pumpkins by the semitruckload from farms across the US.

Brandon Helfner with part of a season’s crop at one of his Mr. Jack O’Lanterns locations (via Jack O’Lanterns)

He estimates he pays $7k-10k per semi. It’s hard to estimate how many pumpkins will be in each load. A truck can generally fit ~56 bins, and each bin could fit 18-22 jumbos, 40-55 jacks, or 1k mini pumpkins the size of a donut — but you won’t know in advance.

“We’ll take on a new lot with the mindset that we’re going to lose money the first year,” Helfer said, referring to upfront costs like a tent, lights, marketing, and maybe a $7.5k bounce house.

Lyra Marble first got into pumpkins on her mother’s California farm in 1987. Today, she runs Mr. Bones, a 4-acre pumpkin patch in the greater Los Angeles area that carts in around 8 semi-loads of pumpkins per year.

“It can be very profitable or I wouldn’t still do it, but it’s also challenging because your entire income is reliant on a few weekends a year,” Marble said.

“A lot of people think I only have to work 2 months out of the year, but it’s intense and stressful to put a show together so quickly that’s dependent on nature and the goodwill of long-term customers.”

Lyra Marble, the proprietor of Mr. Bones pumpkin patch in Culver City, poses in front of one of her many attractions: a house made out of pumpkins (Pascal Shirley via Mr. Bones)

Like agritourism operations, urban patches must also put on a show or lose customers to grocery stores:

- At Mr. Bones, visitors will find a village of adorable houses made of pumpkins, inflatables, kiddie straw mazes, and spider-themed bounce houses Marble designed herself. (The photo opps bring in LA celebrities — and this dog.)

- At Mr. Jack O’ Lanterns, kids love the unique slate of activities, including pumpkin bowling, obstacle courses, animal interactions, and pumpkin decorating stations.

Revenue comes from admission and/or activity tickets, plus pumpkin sales. But the key to success, according to both Marble and Helfer, is to be committed to it for the long haul. Attracting and retaining regulars is critical to recouping upfront costs.

And lastly, what about those really big pumpkins?

Annual biggest pumpkin contests regularly crown winners that weigh in at over a ton — like this 2.7k-pound beast recently presented by an Italian farmer.

A big pumpkin comes with bragging rights and often a cash prize:

- A Minnesota man won $16.4k for his 2,350-pound pumpkin ($7/pound) in 2020 at The Safeway World Championship Pumpkin Weigh-Off in Half Moon Bay, California. .

- This year, a Washington farmer won $19.7k for his 2,191-pound behemoth ($9/pound). Had he broken the 2.7k-pound record, he’d have won $30k.

Mark Craven, of Craven Farm in Snohomish, Washington, with an absolute unit of a pumpkin (via Craven Farm)

According to experts we spoke with, a winning pumpkin’s seeds can also fetch $3-$5 each — around 30x to 50x more than your mere mortal pumpkin seed.

A giant pumpkin contains 2k-5k seeds, meaning it can yield $6k-$26k in profit for its owner.

Jack of the Lantern would be proud… but he probably wouldn’t be able to carry it.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story stated that US farmers produce ~770k tons of pumpkins per year. This stat should’ve read 687k tons, or ~1.4B pounds, per year. The article has been updated.