Right about now, more than 150 of the world’s most elite cyclists are charging up Col de la Hourcère in the French Pyrenees.

Over a 3-week period from August 29th to September 20, these aerobic beasts will traverse some 2,165 miles up and over 8 mountain passes. They’ll spend more than 4,800 minutes in the saddle, and reach speeds of up to 63 MPH. They’ll vie to bring their countries, teams — and sponsors — glory.

The Tour de France is a historic and global phenomenon. Each year, fans from more than 180 countries turn in to watch the race.

But despite this popularity, the economics of the sport are largely shrouded in secrecy.

How does the Tour de France — an event that is free to the public — make money? How does the sponsorship model of a professional cycling team work? And how does this all affect how the riders choose to compete?

How the Tour de France makes money

Cycling’s most important race was born out of financial necessity.

At the turn of the 20th century, a French newspaper called L’Auto was struggling to stay afloat. The paper’s staff was asked to come up with ways to increase circulation — and Géo Lefèvre, a 26-year-old sportswriter, suggested putting on the biggest cycling race the country had ever seen.

Launched in 1903, the Tour de France was an immediate success.

In its first year, the Tour nearly tripled L’Auto’s circulation from 25k to 65k newspapers per day — enough to kill off their main competitor, Le Vélo. Over the next 3 decades, this figure would see a 34x increase.

A front-page L’Auto story in 1903, announcing the arrival of the newly-created Tour de France (L’Equipe)

During WWII, the Tour was put on hold. When peacetime resumed, L’Auto — which had been taken over by a consortium of pro-Nazi Germans — was shuttered and ownership of the Tour was shifted to a successor paper, L’Équipe.

Up until the 1960s, the newspapers had monetized the tour in a number of ways:

- They auctioned off stops on the route to the highest-bidding cities.

- They charged companies a fee to follow riders in logo-plastered publicity “caravans” and throw out swag to spectators.

- They rented out physical ad space along the route.

- They allowed local brands to sponsor the tour.

The Tour’s revenue streams were largely focused on monetizing the large crowds that gathered along the route. And early on, there were concerns that an overabundance of brands and sponsors would corrupt the purity of the sport.

“This caravan of 60 gaudy trucks singing across the countryside…is a shameful spectacle,” the French journalist Pierre Bost wrote of the caravans. “It bellows, it plays ugly music, it’s sad, it’s ugly, it smells of vulgarity and money.”

Despite this diversification of revenue streams, the Tour still operated with a deficit.

But this changed when the race was taken over by its present-day owner, the privately-owned French sports organizer, Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO), in 1965.

The ASO pounced on advances in TV broadcast technology and focused on building out the Tour’s global audience. Between 1980 and 2010, revenue increased by 20x — and TV rights became a central part of its business model.

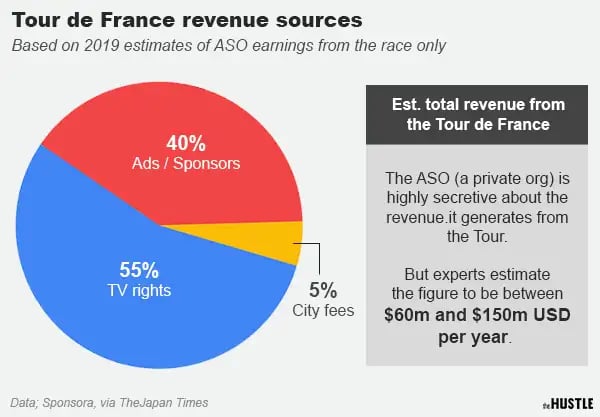

Today, the Tour de France’s revenue breakdown looks something like this:

(Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Town hosting fees (5% of revenue) are no longer a significant income source, but locales still shell out big bucks to be included on the route, which changes year to year. Denmark reportedly spent $3.9m USD to host 3 stages of another major race, the Giro d’Italia.

Sponsorships (40%) are still critical to the race’s bottom line and have significantly evolved. Among them:

- Publicity caravans: Some 33 brands reportedly pay $250k to $600k each to be in the caravan. During the 21-day race, they collectively hand out 15m items to fans — t-shirts, laundry soap, keyrings, meat sticks. The procession of 250 vehicles is 12 miles long and takes 45 minutes to pass by.

- Special jerseys: In the Tour, there are 4 special jerseys worn by riders: yellow (overall leader), green (best sprinter), polka dot (best climber), and white (best young rider). The bank LCL spends ~$12m per year to put its name on the yellow jersey; carmaker Skoda drops $4m on the green jersey.

- Dozens of misc. partnerships: These range from Century 21 (real estate firm) running house giveaway promos, to Tissot (watchmaker) sponsoring time trials.

TV broadcasting rights (55%) have now been sold in 186 of the world’s 195 countries. Streaming the race requires 260 camera people, and 35 vehicles, and 6 aircraft. One major deal with France Télévisions is reportedly worth ~$25m per year alone.

Top: Romain Bardet charges through Alpe d’Huez during the 2018 Tour de France (Pool/Getty Images); Bottom: The peloton are cheered on by the crowd during stage 9 of the 2013 Tour (Doug Pensinger/Getty Images)

So, how much money does the Tour de France bring in per year?

The ASO is incredibly secretive about its finances. But over the years, researchers and French journalists have managed to piece together bits of data from public filings.

Sources The Hustle spoke with estimate the Tour’s revenue to be somewhere between $60m and $150m per year — about 50% of the ASO’s total annual income. Based on historical revenue data, the ASO has ~21% profit margin. So, a very rough estimate would be that the organization enjoys a $12m to $30m annual profit from the race.

“The Tour de France exists to make money,” says Jean-François Mignot, a demographer who has studied the economics of cycling. “It’s a commercial race, and it’s owned by people whose main goal is to make money off of it.”

But the organizer is only one moving part of the Tour de France: a second thriving economy has been built around the teams and riders who compete there.

The business of professional cycling teams

This year’s Tour features 178 cyclists on 22 different professional teams.

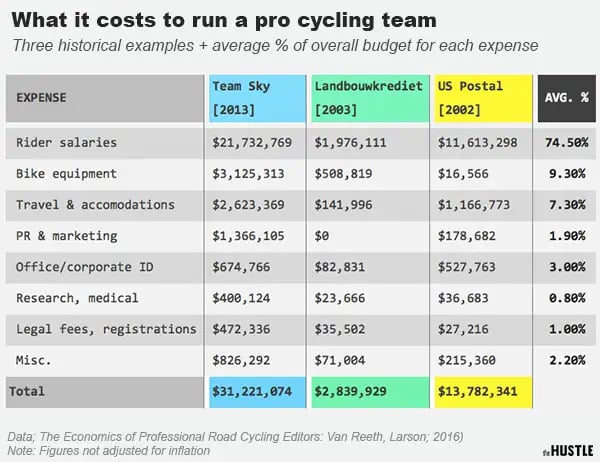

Like the Tour itself, there’s a fiscal omertà (code of silence) surrounding these teams’ budgets. But a 2016 research volume laid out some insight from 3 past teams:

Note: Figures not adjusted for inflation to give a true sense of budgets at the time (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Rider salaries account for the bulk of a team’s budget — but gear costs are no joke.

A video posted by Team Sky (since renamed Ineos Grenadiers) in 2016 outlined an absurd list of resources required for 9 riders during the Tour de France, including:

- 34 staff members (mechanics, drivers, sports doctors, nutritionists)

- 55 bikes (6 per rider), at ~$13k each

- 80 spare wheels, 82 spare cassettes, and 57 spare chains

- 4,360 energy gels and bars + 3,300 water bottles

- 40 bottles of massage cream

- 100 rolls of bar tape (changed every 4 days)

- 5 air purifiers, 9 AC units, and 9 dehumidifiers

All in, today’s top-level cycling teams can easily exceed a $20m annual budget.

But these teams don’t get any piece of the Tour’s revenue. They don’t sell tickets (the event is free to the public). They don’t even have their own merchandise.

How do they fund all of this?

Cycling teams have a very strange — if not deeply flawed — financing model: they have to rely on sponsors or donors to survive.

Teams have all kinds of sub-sponsors for their bikes, gear, and nutrition. But ~70% of their budget comes from the title sponsor, which pays a pro team somewhere in the range of $5m to $15m to name the team and plasters its logo all over the uniforms.

The TV time these sponsors get often comes with healthy dividends: the sports intelligence firm, Repucom, analyzed 325 professional cycling sponsors in 2012 WorldTour (a series of 38 races including the Tour de France) and found that the average team was worth $88.4m in media exposure to a title sponsor.

Take a look at the title sponsors of this year’s 22 Tour de France teams:

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

The corporate sponsors of today’s cycling teams are almost exclusively boring (but stable) conglomerates: insurance companies, telecommunications firms, commercial manufacturers. And there’s a reason for this.

Until the mid-1950s, only bicycle companies were permitted to sponsor teams. But when bike sales tanked in the ‘60s, a potpourri of local products — alcohol, cigars, face creams, hazelnut spreads — hopped in to fill the void.

The rise of live broadcasting drew in international corporations that saw value in reaching a broader global market. The UCI (cycling’s governing body) also implemented a new professional licensing system that drove up costs.

Between 1992 and 2014, the average pro-level cycling team budget increased from $3.6m to $15.5m. The little guys were priced out.

Now, the sport is now seeing a new trend: a rise in wealthy benefactors and oil-rich countries that infuse teams with up to 3x the capital of corporations.

In 2019, for instance, the English industrialist Jim Ratcliffe (net worth $21.4B) purchased Team Sky and renamed it after his chemical firm, Ineos. He’s since infused the team with a reported ~$47m annual budget — heads and shoulders above any other pro team.

Team Israel Start-Up Nation depends on money that comes directly from Sylvan Adams, a Canadian real estate tycoon. Likewise, Mitchelton-Scott relies on cash infusions from the Australian millionaire Gerry Ryan.

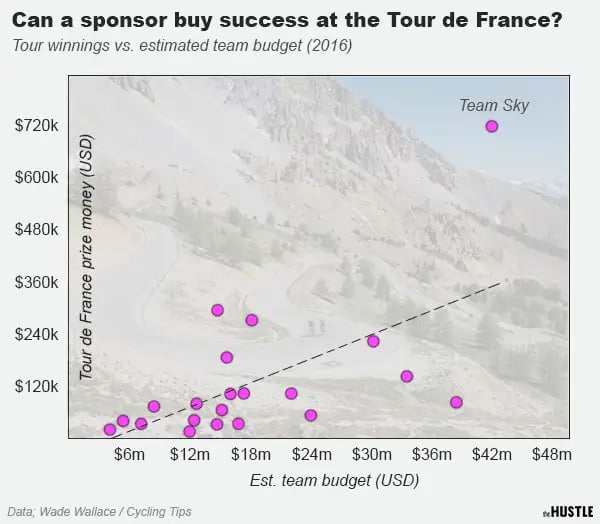

A study from the blog Cycling Tips mapped out the correlation between sponsor money and financial success at the 2016 Tour de France (Data: Cycling Tips; Graphic: Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

This dependency on one rich individual can implode: when Russian billionaire Oleg Tinkov stepped away from funding his team, Tinkoff, in 2015, it folded.

But some say it also causes a competitive imbalance that erodes the marketability of the sport.

“[They’re] purchasing the ability to win,” pro cycling manager Jonathan Vaughters told the Daily Mail. “You’re looking at an almost impenetrable wall of money. You can go and buy all the best riders. The question for the sport is, ‘If they are all on one team, is it fun for spectators to watch?’”

And what about the riders?

For most of the first half of the 20th century, pro cyclists were not paid a salary and had to scrape together an income by winning races. Prize money was their lifeblood.

If that were still the case today, most riders would be screwed.

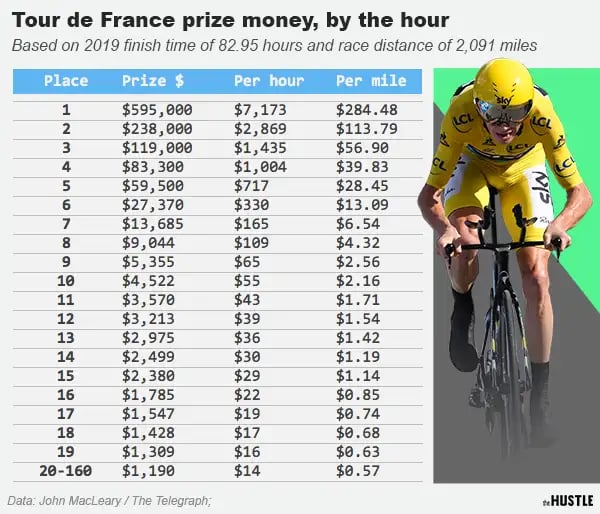

The total prize money at the Tour de France is relatively small, at ~$2.7m (€2.3m). The overall winner (yellow jersey) gets the bulk of that — $595k (€500k) of that — and each subsequent overall placing gets a diminishing amount, down to $1.2k for 20th to 160th place.

Winners of other jerseys (green, polka dot, white) take home between $24k (€20k) to $30k (€25k) each. And various smaller sums are given out for each stage for sprints, time trials, categorized climbs, and “combativity” (aggressiveness).

Let’s, for a second, assume this was riders’ only source of income.

The first few individual finishers would do okay for themselves — but bottom-tier finishers would make more working in retail for 3 weeks than racing in one of the most prestigious cycling races in the world:

(Data: John MacLeary / The Telegraph; Graphic: Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

In reality, this prize money isn’t an important factor in racers’ income. In fact, the winner customarily shares it with the whole team.

Today, their livelihood hinges on sponsorship dollars.

The mandated minimum wage for a pro cyclist who participates in the Tour de France is ~$35k. But many pros make 5-10x that — and the top dogs, like Peter Sagan and 4-time Tour winner Chris Froome, command salaries of $6m+ per year.

This dependency comes at a cost: riders must formulate their Tour de France strategy around maximizing visibility for sponsors.

Winning the tour is fantastic — but not necessary — for brand exposure. Often, you’ll see lesser-known riders break away from the pack to give sponsors media time, even if it isn’t technically the best thing to do.

“The entire Tour is about getting eyes on the company on your jersey,” an ex-pro who wished to remain anonymous told us. “Because if the sponsor isn’t happy and cuts funding, your team is probably shit out of luck.”

The pack during the 2nd and 3rd stages of the 2020 Tour de France (Marco Bertorello / AFP, via Getty Images)

This year, keeping sponsors happy is more important than ever.

The pandemic has strained not just the ecosystem of cycling sponsors, but the sport at large. Some riders have taken pay cuts, or deferred as much as 70% of their salaries, in a bid to keep their teams afloat through the crisis.

Many in the cycling community feel that it’s due time to reevaluate the sport’s business model.

“At the end of the day, race organizers make money and sponsors sell more products,” writes Chris Williams, a pro cyclist from Australia. “But teams fight for existence.”