Shortly after 7pm on April 24th, 1980, millions of Pennsylvanians watched intently as a third and final ping-pong ball shot up the tube of a machine on live television.

“And there you have it,” exclaimed the station’s beloved announcer, Nick Perry. “Today’s Pennsylvania lottery daily number: 6-6-6!”

As the cheesy music faded and the lights dimmed, Perry implored lucky ticket holders at home to claim their prizes: “If you’ve got it, come and get it!”

What the public didn’t know was that Perry — along with a rag-tag group made up of co-workers, church friends, and a state lottery official — had fixed the entire thing in his favor. Through an elaborate ruse involving syringes and latex paint, he’d just netted himself and his associates $1.2m ($3.7m today) in winning tickets.

Soon, one of the largest scandals in state lottery history would come crashing down.

The legend of Papa Nick

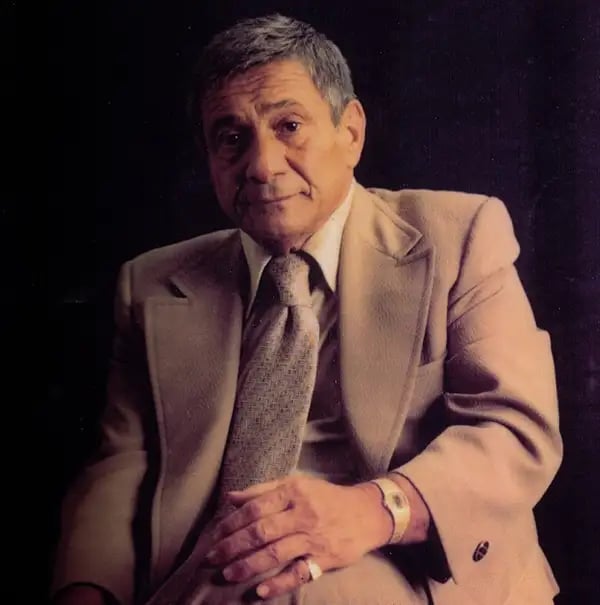

In the late 1970s, Nick Perry (real name, Nicholas Katsafanas) was Pittsburgh royalty.

A radio and TV veteran of 30 years, Perry was affable, charming, and debonair — tall and tan, with whisked white hair and an ever-present ivory smile.

As an announcer and host for WTAE Channel 4 — Pittsburgh’s leading TV station, and one of the largest local networks in the country — his shows (Polka Party, Championship Bowling, Bowling for Dollars) attracted legions of adoring fans who called him “Papa Nick.”

A Navy vet and church choir leader, he held the public’s unwavering trust. “He was always surrounded by people who loved him,” a former co-worker later said.

When Pennsylvania launched its daily lottery, in 1977, WTAE won the rights to broadcast the drawings state-wide every night.

And the station could think of no better man to entrust as the drawing’s announcer than Pittsburgh’s golden boy, Nick Perry.

The Daily Number

Dubbed the Daily Number, the draw quickly became the most popular lottery game in the state — and one of the 5 largest in America. Its proceeds, which soared to hundreds of millions of dollars, were the chief revenue source for funding senior citizen programs.

The lottery itself was simple.

An entrant would buy a ticket staking anywhere from $0.50 to $5 on a 3-digit number between 000 and 999, in a specific order.

Every night at 6:59pm, a lottery official would wheel out 3 air-powered machines, each filled with a set of ping-pong balls numbered 0 to 9. On live television, a senior citizen (selected at random from a local elderly home) would remove the cap from the top of each machine, propelling a random numbered ball up a clear plastic chute.

The resulting 3-digit combination was the daily winner. Lucky entrants would receive $500 for every $1 wagered. (In those days, bets were pretty humble; most payouts were in the thousands, not millions, of dollars.)

Like most lotteries at the time, the Daily Number followed a tight security protocol.

When not in use, the lottery machines and balls were locked in a WTAE storage room that required 2 keys to open; one was held by the TV station, the other by the state’s lottery bureau. The balls were routinely examined by an independent laboratory, and were only permitted to have a 1.75 milligram variation in mass — about half the weight of an ant.

As the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette once wrote, Pennsylvania lottery’s reputation “rivaled that of ancient Rome’s Vestal Virgins.” The state prided itself on the squeaky clean reputation of its daily drawing, and that of Perry, the man at its helm.

But unbeknownst to them, Perry was scrutinizing flaws in the system — and looking for an opportunity to exploit it.

The scheme

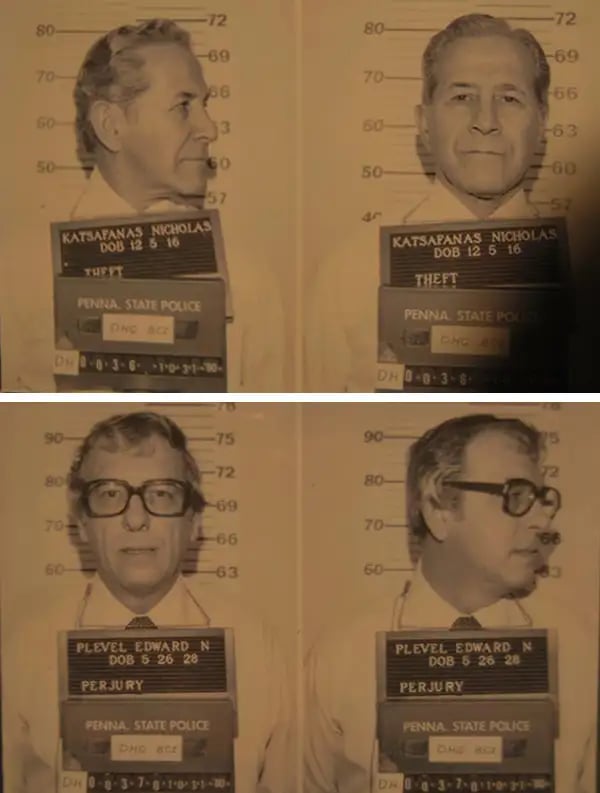

In February of 1980, Perry sparked a friendship with Edward Plevel, a 52-year-old state lottery security officer who was entrusted with guarding the machines and balls.

Once a mutual trust was established, Perry carefully broached the possibility of a fixed lottery: In theory, he told Plevel, if he had access to the storage room, he could weigh down all the balls except a few numbers, dramatically reduce the possible winning combinations, hedge heavy bets on those numbers, and walk away with millions.

Plevel was intrigued, and agreed to give Perry the access he needed. Soon after, Perry began to put his plan into action.

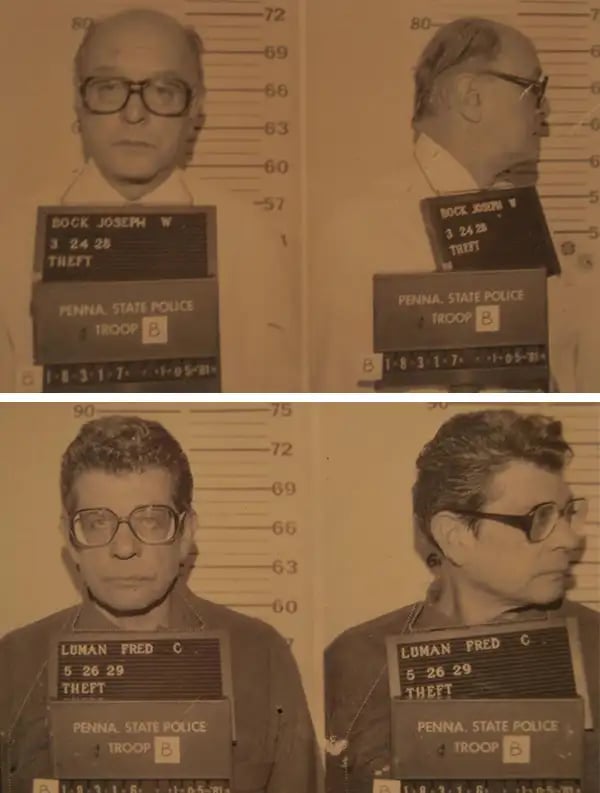

The first step was to find someone he trusted who could create replica sets of the lottery balls. For this, he turned to WTAE’s ex-art director and resident lettering expert, Joseph Bock.

“What would you say if I told you you could make $100k?” Perry allegedly asked Bock at the station one day, according to a later account in the Post-Gazette.

Bock scoffed. “Who do I have to kill?”

Perry gave Bock 12 syringes and a weighing scale and instructed him to buy 30 ping-pong balls from a sporting goods store identical to those used in the machines.

Following Perry’s instructions, Bock painstakingly replicated each ball by hand — 3 sets, numbered 0 through 9. Then, he set out to find a subtle way to weigh down the balls that weren’t a 4 or a 6.

After experimenting with various substances including talcum powder and water, he settled on a tiny amount of white latex paint — just enough to prevent them from rising up to the top of the machines and getting sucked up into the chutes.

In an untampered lottery, the odds of any 3-digit number were 1 in 1k. If Perry’s plan worked, only the unweighted 4s and 6s would rise to the top, limiting the winning number to 8 possible combinations: 444, 446, 464, 466, 644, 646, 664, and 666.

Everything was in place. Now, all Perry needed to do was place his bets.

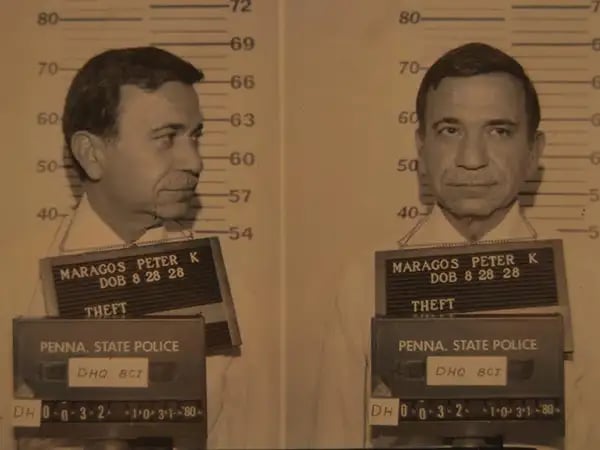

Perry couldn’t buy lottery tickets himself — it was too suspicious. So, he met with two childhood friends, Peter and Jack Maragos, at a pew in St. Nicholas Orthodox Church.

Part-owners of a small cigarette vending machine business, the Maragos brothers were intrigued by the thrill of a big payout. They agreed to buy the tickets, and soon roped a third brother, James, and his wife, Jean, into the scheme.

The family unit delegated the stores where they’d purchase tickets, and assembled $20k in cash. Then, they waited for Perry’s command.

The big day

On the morning of April 24, 1980, the Maragos brothers rocketed around Philadelphia in an old white Cadillac.

Targeting small mom-and-pop outlets — places with names like Al and Virginia’s Variety Store, Herman’s Cigar Store, Squirrel Hill Newsstand, and Dew Drop Inn — they placed thousands of $1 bets on the 8 possible combinations of 4 and 6.

Meanwhile, Perry finalized his preparations at the studio.

Typically, the senior citizen selected to help with the lottery would run through a practice drawing at 6:30pm, 29 minutes prior to airing. That day, Violet Lowrey, the chosen octogenarian, was carted into a green room upon arrival and remained there until 6:55.

During this time, Bock handed off the weighted balls to another employee in on the fix, stagehand Fred Luman, who furtively swapped them into the machines as Plevel looked the other way.

Once the job was done, Luman rolled the machines out onto the studio floor, gave a nod to Perry, and disappeared into the shadows of the corridor.

At 6:59, the broadcast went live.

To millions of viewers across Pennsylvania, nothing appeared out of the ordinary. Perry was introduced with his usual sign-on — “The man with all the dollars! The kingpin himself!” — and Plevel escorted Lowrey to the machines.

Lowrey removed the cap and the first ball shot up the chute: a 6. Then came ball #2: “Another 6!” exclaimed Perry. Seconds later, the third ball landed. The winning number — 6-6-6 — danced across the screen.

A half-hour later, Bock was back at home, lighting fire to a paint can filled with the 30 weighted ping-pong balls.

A gangster gives a tip

It seemed that Perry and his cronies had pulled off the perfect crime.

The Maragos had selected 6-6-6 on roughly 2.4k of their 14k $1 tickets. With a $500 to $1 payout, the crew was looking at a payout of $1.2m ($3.9m in 2019 dollars) — an unheard-of amount for a state lottery at the time. Over the next few days, the brothers cashed in a few hundred tickets and delivered Perry $35k in cash — once at a cemetery, a second time behind a shopping center.

Unbeknownst to them, there were rumblings on the street that the game had been fixed.

As it turned out, the Maragos brothers had also placed bets with underground bookies, who had noticed the unusually high number of hedges on combinations containing the numbers 4 and 6. They refused to pay out winnings on 6-6-6, and alerted their boss, Tony Grosso.

A convicted numbers boss, Grosso had been running his own $30m-a-year illegal daily lottery on the streets of Pittsburgh for 40 years — and he was happy to tip-off local reporter, Sandy Starobin, of a potential fix in the state lottery, which he considered the competition.

In May 1980, an investigation was opened by Pennsylvania governor, Richard Thornburgh.

Though lottery officials (including Plevel) pooh-poohed the idea of an inside job, investigators received a tip from the owner of the Dew Drop Inn: Weeks earlier, two men in a white Cadillac had bought hundreds of lottery tickets — all combinations of 4 and 6 — and placed a call to a mystery man.

The paper trail and phone records led them to the door of Peter and Jack Maragos, who promptly agreed to testify for the state in exchange for dropped charges. Bock and Luman followed and gave the state two names: Perry and Plevel.

On May 11, 1981, reporters (including Perry’s colleagues at WTAE) gathered at the county courthouse in Harrisburg for a criminal trial against the two men.

Over a week, 25 witnesses — including co-conspirators, shop owners, and angry senior citizens — took the stand. After 6.5 hours of deliberation, a jury of 12 found Perry and Plevel guilty of criminal conspiracy, criminal mischief, theft by deception, and “rigging a publicly exhibited contest.”

Neither man showed emotion as the sentences were read: 3 to 7 years for Perry; 2 to 7 years for Plevel.

As the tanned TV star was led from the courtroom in shackles, his fans grappled with the news. “[It’s like] Joan of Arc being burned at the stake,” one fan wrote in a Post-Gazette op-ed. “I can’t see why a 63-year-old man who has a good living and is established in the community would do something like this.”

The bowling goods salesman

In the aftermath, WTAE lost the rights to air the daily lottery to a rival station, costing it millions of dollars in lost ad revenue. Eventually, authorities would recover most of the money and uncashed lottery tickets.

Bock, Luman, and the Maragos brothers faded from the public eye after 1981 and settled into quiet, less eventful lives. After serving 18 months, Perry and Plevel were released to a halfway house.

Post-prison, Perry found work at Wissman Bowling Supplies, a bowling outfitter that had provided equipment to his hit show, Bowling for Dollars. In 1988, he made a short-lived return to TV to host a new bowling show, but he never reclaimed his former glory.

When Perry passed away in 2003, at age 86, he was remembered with a two-page spread in the Post-Gazette. He maintained his innocence to the grave.

“Why would I get involved with something like this? For what reason?” he said in a final interview. “I was making good money. They were the best years of my life, actually. I had too many good things going for me.”

The Daily Number game, since renamed the “Pick 3,” now features a security process involving 24-hour video surveillance, RFID-chip-equipped balls, independent auditors, and no less than 6 drawing officials. It brought in $269m in revenue for the state of Pennsylvania in 2018.

Since April 24, 1980, 6-6-6 has been the winning number on 24 occasions — all supposedly scandal-free.

And Pennsylvania lottery officials have since adopted an unofficial slogan: “Be perfect.”