As the great sage Charlie Brown once said: “There are 3 things in life that people like to stare at: a flowing stream, a crackling fire, and a Zamboni clearing the ice.”

Watching one of these machines glide across a skating rink, restoring carved-up ice to glassy perfection, is efficiency in motion. A job that once required 1.5 hours of manual labor can be done by a Zamboni in just a few minutes.

Technically, these contraptions are called ice resurfacers.

But the company that originally invented them in 1950 — Frank J. Zamboni & Co., Inc. — has become so dominant in the niche market that even competing ice resurfacers are sometimes incorrectly called “Zambonis.”

The company has produced 12k+ machines used by pro hockey teams, Olympic Games venues, and recreational ice rinks around the world.

And it all started with the entrepreneurial vision of a 2nd-generation Italian immigrant named Frank J. Zamboni.

From farm to ice rink

Born in 1901, Zamboni spent his childhood on his family’s farm in Idaho, tinkering with mechanical equipment.

According to the Italian-American periodical Fra Noi, Zamboni’s formal education was cut short at the age of 15 when he left school to earn extra income fixing cars.

Frank Zamboni (far left) with his mother, father, and siblings, c. 1905 (Zamboni Company)

In 1920, he moved to Los Angeles to help his older brother run an auto garage. Soon, he saw an opportunity in a different space: refrigeration.

Many industries relied on large chunks of ice to preserve and transport perishable products. Leveraging their mechanical know-how, Zamboni and his brother launched a business that specialized in crafting refrigeration units for dairy farmers.

By 1927, they’d expanded the operation into a plant that produced ice blocks, which they sold wholesale to produce farmers.

But in the mid-1930s, major advancements in air conditioning and cooling technologies threatened to put the brothers out of business…

So, they had a genius pivot

At the time, figure skating was growing in popularity in America.

Buoyed by the Winter Olympics, which debuted in 1924, an industry was emerging for indoor ice skating rinks. But the prevailing tech used to create the ice in the rinks — a grid of underground steel pipes — often left the surface “rippled” and bumpy.

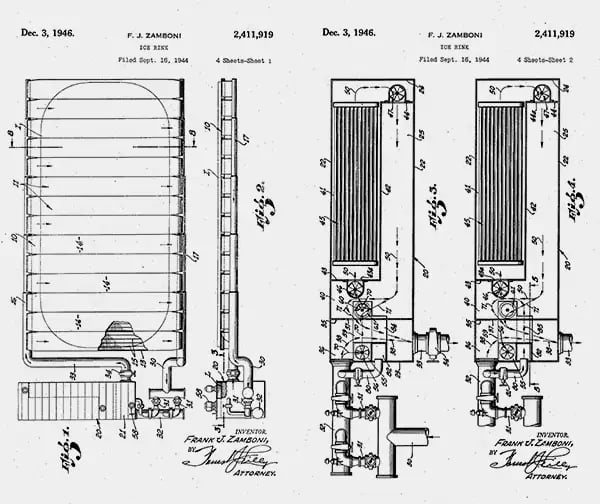

Zamboni’s early patent illustrations for improved ice rink mechanisms (Google Patents)

At his ice plant, Zamboni began to experiment with different cooling methods and soon discovered an alternate solution.

In lieu of pipes, Zamboni circulated brine water and ammonia refrigerant under the ice in “large flat tanks” — an approach that resulted in a smoother, more uniform skating surface.

He secured a patent and, in 1940, teamed up with his cousin and brother to open his own ice skating rink down the street from his ice plant.

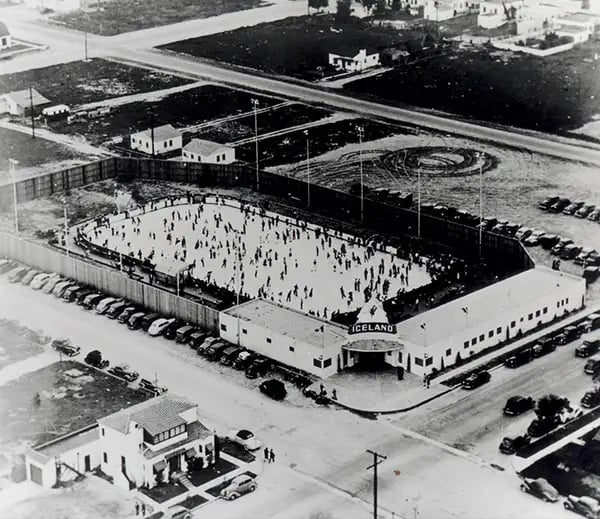

Iceland Skating Rink was unlike anything Southern Californians had seen: The 20k sq. ft. facility — one of the largest in America — could house 800 skaters at once.

The business was a smash hit, attracting 150k skaters per year.

Iceland, in Paramount, CA, c. 1940s. A dome was later added, making it an indoor rink. (Zamboni Company)

But the success of the rink, and its sheer volume of foot traffic, soon raised a secondary concern.

At the end of every business day, the rink’s ice was completely chewed up by skate blades. How could they efficiently restore it for the following day’s crowds?

How to resurface 20k sq. ft. of ice

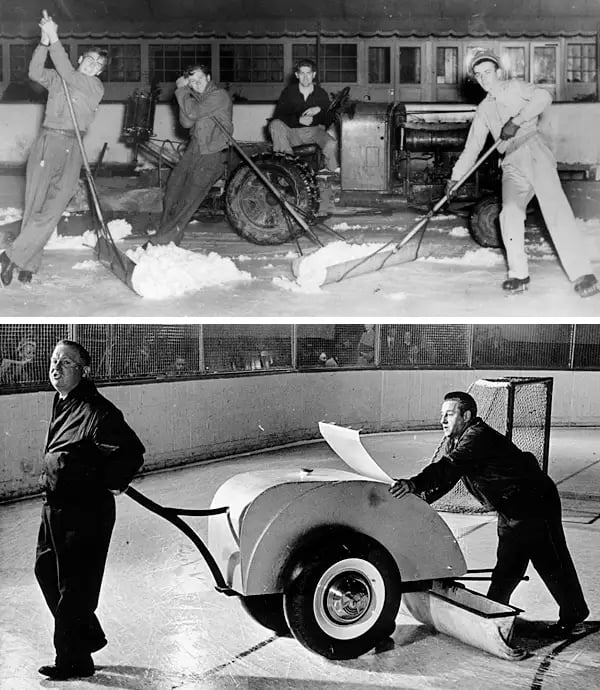

In the early 1940s, skating rinks had a rather daunting procedure for restoring the surface of their damaged ice:

- A tractor would roll across the ice with a scraper in tow.

- Workers would manually shovel up the shavings and “squeegee the dirty water away.”

- The workers would spray on new layers of water.

This process took 4 men up to 1.5 hours to complete — and Zamboni couldn’t stand for it.

Early — and not very efficient — methods of resurfacing ice (Zamboni Company)

For nearly a decade, Zamboni had something of a mad scientist’s lab in the back of the Iceland rink, where he experimented with various mechanical contraptions that could optimize ice resurfacing.

He Frankensteined parts from war surplus vehicles and bomber planes, and ran into numerous issues — chattering blades, malfunctioning snow tanks, lack of tire traction on the slippery ice.

“It took him nine years,” Zamboni’s son, Richard, later told the LA Times. “One of the reasons he stuck with it was that everyone told him he was crazy.”

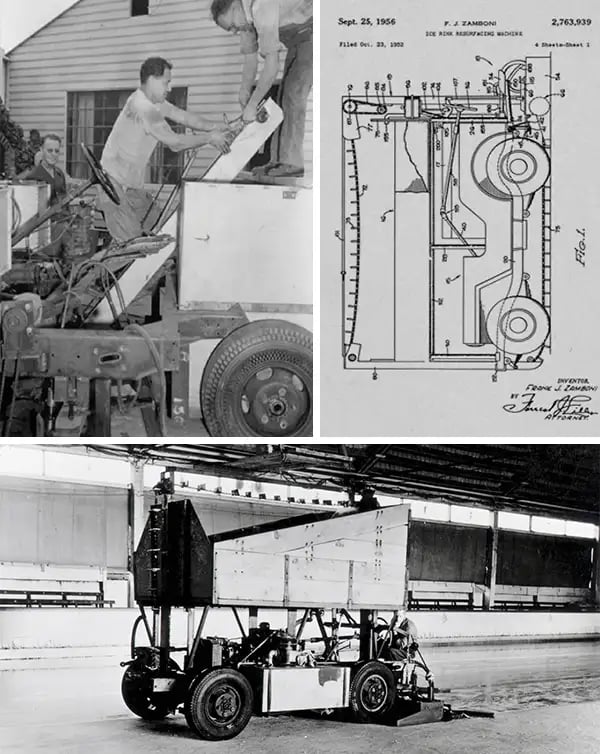

Finally, in 1948, his prototyping led to a breakthrough.

Per Joseph Scafetta, Jr., who profiled Zamboni in 2000, the machine worked like so:

- A blade inside the vehicle shaved the surface of the ice.

- The ice shavings were picked up by a horizontal screw and funneled into a snow tank by a conveyor.

- A second tank sprayed conditioner on the ice to eradicate imperfections.

- A vacuum sucked up dirty water and debris.

- Clean hot water was dispensed on the ice.

Top left: Zamboni working on prototypes; top right: a patent illustration for his early machine; bottom: an ice resurfacer prototype in action (Zamboni Company)

The resulting invention — the Zamboni Ice Resurfacer — could perform all of these tasks in 15 minutes while driving across the ice. (Future machines would improve this time even more.)

In 1949, Zamboni formed Frank J. Zamboni & Co. and began manufacturing his patented machines for sale to the public.

A lucrative, niche industry

Competing ice rinks quickly recognized the utility of Zamboni’s machines.

The entrepreneur sold his first machine to the nearby ice rink Pasadena Winter Garden for $5k ($54k today). But Zamboni’s biggest marketing tool was his own rink, Iceland.

A big break came in 1950 when Sonja Henie — a Norweigian film starlet and Olympic champion skater — spotted one of Zamboni’s contraptions in operation at Iceland and ordered 3 of them for use in her international figure skating tour.

This gave the machine world-wide exposure — and demand soon ballooned.

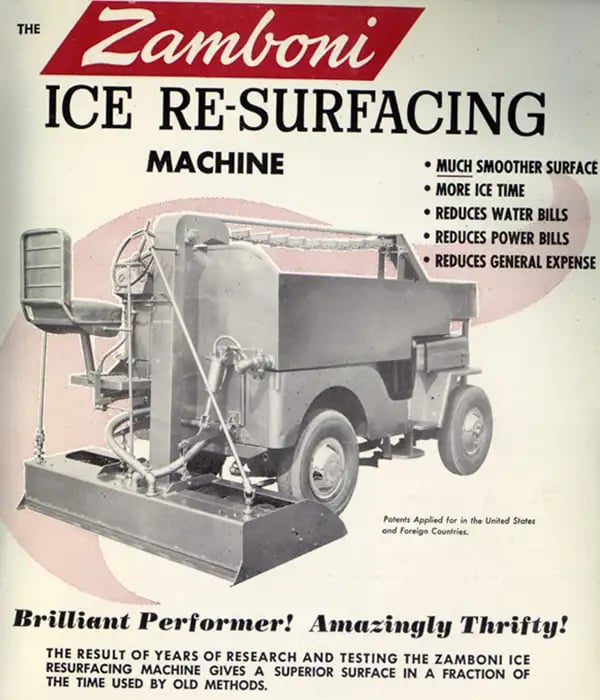

An advertisement for Zamboni machines, c. 1960s (Zamboni Company)

From the 1950s to the early ‘60s, sales figures doubled each year. The company’s customer base expanded to include NHL teams, the Winter Olympics, and touring shows like the Ice Capades.

New owners often expressed concern that the new machines were so fun to watch that they were stealing the limelight. “People will stay in the stands and watch it and not go down to the concession stands,” one stadium owner reportedly told Zamboni.

Zamboni had an astute eye for iteration, based on customer feedback. Over the years, the machines saw various improvements — increased tank capacities, liquid-cooled engines, and later, electric power.

After handing the reins of the company to his son, Richard, in the late ‘60s, Zamboni continued to innovate, inventing machines that rolled up AstroTurf, dumped dirt on cemetery vaults, and cleaned airplanes.

A grasp on the market

Frank J. Zamboni died of lung cancer complications in 1987, at the age of 87.

But today, under the leadership of his grandson, the company he built continues to dominate the ice resurfacing market.

Since 1949, the company has sold more than 12k ice resurfacing machines. Between its 3 manufacturing plants in Los Angeles, Canada, and Sweden, it rolls out ~250 new machines per year, which cost anywhere from $10k to $175k+ depending on size.

Some of this cost pays for itself: rinks often make money by selling ad space (anywhere from $5k/year for a smaller arena up to $50k+ for the NHL) on their Zamboni machines.

Zamboni (right) with his son Richard (later the company’s president) in 1985 (Bob Riha Jr. / WireImage)

Though ice rinks have seen slowing growth in the US, Zamboni has continued to mine customers in growing foreign markets. Fears about niche market saturation have never been fully realized.

To secure limited business, Zamboni often has to slug it out with a few competitors like Ontario’s Resurfice Corporation.

But the Zamboni company enjoys a competitive advantage that goes back to the roots of Frank Zamboni, who has since been inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

“If our name had been Smith or Brown, I don’t think any of this would have happened,” Zamboni’s son Richard later told the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

“It’s kind of a screwball name. There’s such a uniqueness to it, the machine kind of took on a character of its own. My father was always surprised by that.”