“Where the hell have you been? I haven’t seen you in 6 months!”

Ira Belfer rises from his throne (a well-worn dining chair from the 1980s), circumvents a countertop cluttered with VHS tapes, and lumbers toward a well-tanned man in a polo shirt who’s just walked into his store. “What, you’re done watching movies now?”

It’s a question Belfer has found himself asking a lot in recent years.

The world is not the same place it was when he opened his shop, Captain Video, in 1985. At 65, he’s now the grizzled veteran of a dying industry. He’s witnessed the boom and bust of the video store. He’s watched the rental titans crumble. He’s weathered the onslaught of the digital age — on-demand television, Redbox, Netflix, Amazon Prime.

But as the world evolved, Captain Video stayed largely frozen in time. And that’s exactly what has kept it in business.

The birth of a video store

In the late ‘70s, Belfer, then a 23-year-old LP salesman, packed his bags and moved from Brooklyn to California.

He bounced around for a few years, selling ads on the radio and managing a record store. Then, in 1982, he landed a gig at a burgeoning business — Captain Video, a small chain of VHS rental franchises in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Six months into Belfer’s job, his father came out for a visit and witnessed the chain’s Daly City store rent 2,500 movies in a single night at $3 a pop.

“He said, ‘This is terrific — we need to get you your own store!’” recalls Belfer.

With a $100,000 investment, Belfer franchised his own Captain Video store in San Mateo, California, a quiet suburb 20 miles south of San Francisco.

On Saturday, March 23, 1985 — 7 months before the first Blockbuster broke ground — Belfer opened for business.

In those days, inventory was expensive. A brand-new VHS tape retailed for around $75; at his rental rate ($3 for 5 days), Belfer would have to rent out a film 25 times just to get his money back.

On paper, the business model was a bit shaky: It required a sizeable investment in technology that was in a perpetual state of evolution. Nonetheless, a video rental revolution was on the horizon.

Streaming killed the video star

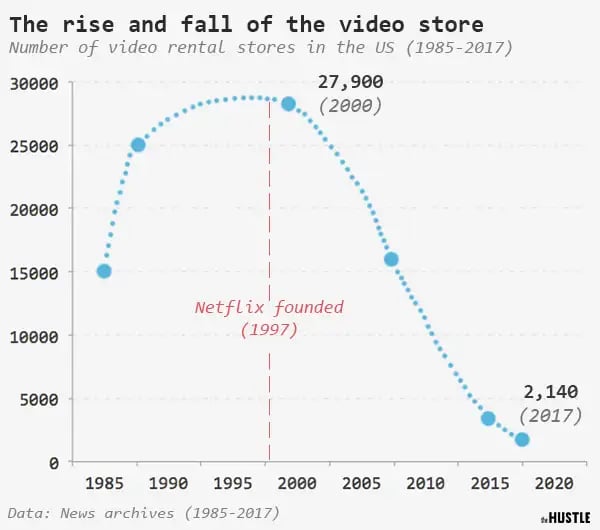

By the end of 1985, there were 15,000 video stores in operation across America; by the late ‘90s, there were nearly 30,000.

Today, it is estimated that only ~2,000 remain.

Even the giants have fallen: Blockbuster, once a multi-billion-dollar company with 4,500 stores in the US, touts only one remaining franchise on Earth. The chain declared bankruptcy in 2010 — and its one-time formidable rival, Movie Gallery (owner of Hollywood Video), shortly followed suit.

Last year alone, total revenue generated from US brick and mortar video rentals fell 20%, to $317m — the equivalent of about $150,000 per shop.

Driven by the rise of on-demand television, digital rental kiosks (Redbox), and streaming services (Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime), this dramatic dip has distinguished the video rental business as one of America’s “top dying industries.”

Redbox now controls 51% of all physical movie rentals in the US, and the major streaming services collectively have 375m paying subscribers — most of whom no longer leave the house to watch a movie. Movie store clerks have been vanquished by algorithms that track our cinematic tastes and churn out lists of “smart recommendations.”

But 34 years after opening for business, Captain Video still stands.

“All these new companies have tried to put me out of business,” says Belfer. “But you can never chase the little guy away if the little guy is dedicated and wants to fight.”

The movie man

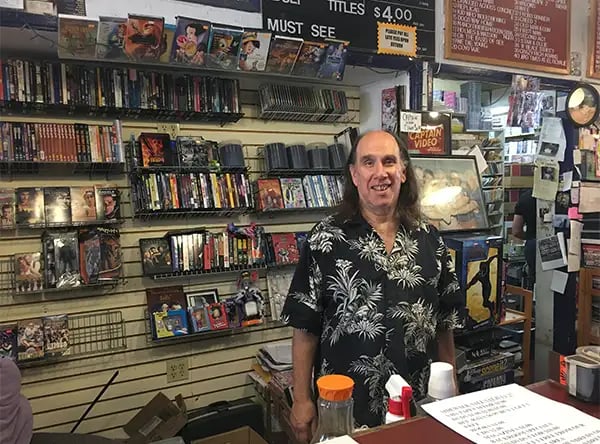

On a hot Wednesday afternoon in July, Belfer is propped near the cash register at Captain Video, sifting through a pile of Blu-ray discs.

Sporting a skullet (bald on top, flowing mane in the back) and a gray Hawaiian shirt, he’s flanked by Hollywood knick-knacks: Wonder Woman figurines, Black Panther posters, a life-size plastic chihuahua, a copy of Entertainment Weekly with Jonah Hill on the cover.

A bulletin board of his favorite films (“Captain’s Classics”) hangs high on the wall. The #2 spot is occupied by Field of Dreams (1989), the only movie that ever made him cry.

“When I put the key in the door every morning, I don’t know if there are going to be 4 people waiting for me, or if I won’t see a soul for 4 hours,” he says.

When a customer does walk through the door, he or she is often greeted by name.

“Hey, Danny!” he hollers at a stocky man with a crew cut. “Rutger Hauer died today.”

“Who?”

“Rutger Hauer — the blonde German guy in Bladerunner. You know… Rutger Hauer!”

Danny Martineau, 54, has been a regular since 2011. After arthritis forced him to retire early from a gig as a medical equipment mechanic, he developed an affinity for old action flicks — anything starring Jean-Claude Van Damme or Steven Segal.

“I like hanging out here,” he says. “We tell each other all of our problems. It’s like an open complaint department.”

Regulars describe Captain Video as a real-life Cheers: A place where people — mostly older men — gather to talk about everything from politics to heart health.

“I have 6 or 7 customers who’ve been coming here for 34 years,” says Belfer. “I’ve seen them grow up. I’ve seen them have kids. I’ve seen people in their family die.”

For Captain Video loyalists, it’s a bond that can’t be replaced by computers.

“A lot of my customers like the old way of doing things,” he says. “They are people who don’t like big corporations, like Comcast. They’ve been burned so many times and don’t want to give them money. They see me as an independent guy, and they trust me.”

Like an algorithm, Belfer knows his customer’s tastes — who wants gore, who wants sex, who wants religious movies. When Rob Caughlan, another regular, struts in, Belfer preemptively recommends a drama. “Rob’s wife, Diana, hates the bloody stuff,” he says.

Unknowingly, he even mimics the popular subscription box trend: One Captain Video customer comes by every Friday night and spends $300 to $500 on a crate of films personally curated to his tastes by Belfer.

Business, $2 at a time

Belfer says he averages $150,000 per year in revenue; after expenses (inventory, rent, insurance, and utilities), he makes just enough to survive.

His margins are so low that even a 10% dip can have dramatic consequences: During the Great Recession, he had a “near-death” experience and had to let the last of his employees go. In recent years, things have stayed relatively steady, though he constantly has to find new ways to scrape together an income.

As rentals have declined, Belfer has turned to quick online and in-store hardcopy sales: He acquires hauls of tapes and discs for $0.10 to $0.25 a pop, then offloads them on Craigslist for $1 to $3, often to kids in their 20s who buy them for “nostalgic value.”

Today, these micro sales make up 70% of his business.

Another sizeable chunk of Belfer’s revenue (a combined 40% of all rentals and hardcopy sales) comes from Captain Video’s adult fare.

“Unfortunately, I’ve been able to stay in business because of that area,” he says, thumbing toward a side room that’s cordoned off by a black curtain.

Captain Video’s weekend crowd is generally wholesome — families, kids, couples. But on weekdays, the shop is populated by men who forage for XXX titles with names like Forrest Hump, The Da Vinci Load, and Big Melons 5.

Though online porn now accounts for more web traffic than Netflix and Amazon Prime combined, furtive masturbators still prefer hard copies: Of 12 customers who trickle through Captain Video on a recent afternoon, 8 bee-line for the curtain.

One of these men, dressed in a crisp blue dress shirt, is a particularly big spender. “You see that guy?” Belfer nods. “He spent close to $10,000 on adult films last year.” That works to around 7% of Captain Video’s entire annual revenue.

Belfer does his best to keep Captain Video family-friendly, and the porn discreet. Sometimes, though, the duality of his customer base comes crashing to a head.

“Every now and then, some guy will bring in a huge box of adult films when a mother is standing at the counter with her kid. She’ll be like, ‘Oh my God, this is horrible!’ And I have to say, ‘Lady, I’m sorry! I’m just trying to run a business here!’”

The show goes on

To keep things afloat, Belfer works 12 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Since 2010, he’s only closed his doors twice — once for jury duty, and another time when he was hospitalized with an infection. He’s often in the store well past 10 pm, when the streets are quiet and couples are nestled at home in bed, binging on Netflix.

“This place cost me my marriage,” Belfer says, sipping a can of Pepsi from a straw. “She told me, ‘Ira, you work too much; it’s either me or the store.’”

Belfer chose the store — and today, it’s the sole surviving Captain Video.

“The only reason I’m able to survive is that I hustle all the time,” he says. “I have to fight for every dime.”

Being one of the last survivors in a dying industry has its challenges. For one, he’s outlasted most of the industry’s technologies: The world’s last dedicated VCR manufacturer closed shop in 2016; its one-time competitor, Betamax, stopped producing machines in 2002.

Belfer is aware that he’s a relic (“Everything has changed except for me; I’m still pushing the same shit,” he admits). But to his loyalists, he’s a VHS superhero — a capeless captain who staves off the villainous march of progress.

“I’ve earned some respect around here,” he says, leaning back in his chair. “People have called me an icon, a legend—”

“He’s a dinosaur!” interjects Danny, who’s still milling around 45 minutes later.

“Get outta here!” retorts Belfer. “Go buy something.”