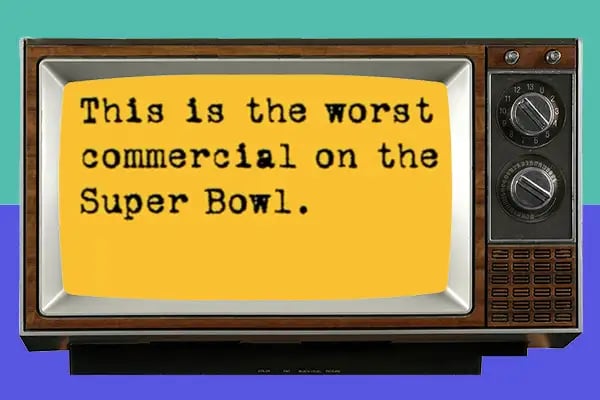

On January 30, 2000, a single sentence set against a yellow background appeared on the TV screens of more than 130m Super Bowl viewers.

“This is the worst commercial on the Super Bowl,” the advertisement said.

It was homemade by the founders of a relatively unknown startup called LifeMinders.com in just 6 days. It lasted 30 seconds — and cost $2.1m (watch it here).

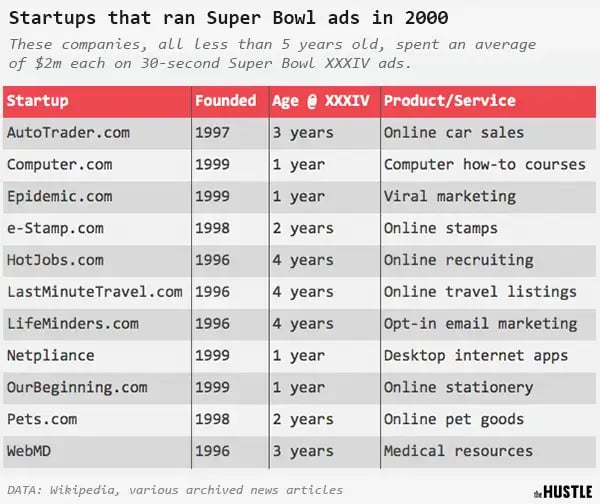

If it sounds unusual, it wasn’t: Not that year, anyway. Eleven startups spent millions for 30-second spots in Super Bowl XXXIV.

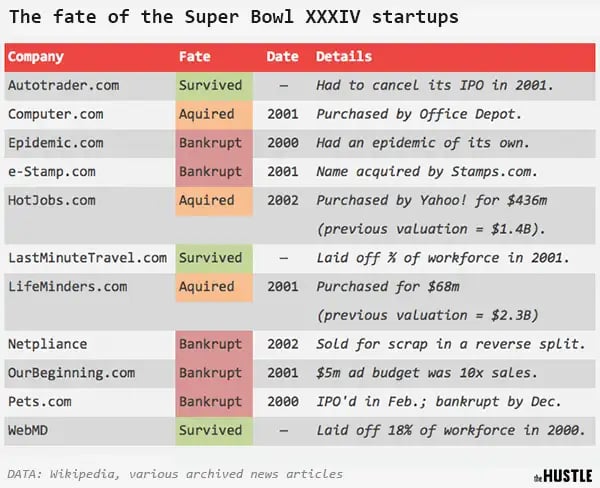

The very next year, 8 of these 11 companies had either gone bankrupt or been sold in fire sales.

To be clear, the cost of these ads didn’t cause these companies to collapse (blame the dot-com bubble bursting for that).

But few startups before or since that year have placed such big bets on the Super Bowl. We couldn’t help but wonder: Why did so many startups throw Hail Marys back then?

To answer that question, we spoke with advertising professors and some of the startup execs who bet big on ads in 2000.

They all agreed that startups can score in the Super Bowl if they’re smart. But they disagreed on whether the ads of 2000 were “worth it.” That disagreement revealed what really set Super Bowl XXXIV apart: Risk.

Big brand consultants mitigate risk; startup founders seek it out.

So the startup Super Bowl wasn’t some anomaly after all. It was startup founders doing what they do best: risking it all to win big. The only difference was that in the heady days of the dot-com bubble, there were fewer people to tell them not to.

Startups went long at Super Bowl XXXIV

The 11 startups that bought ads for 2000’s Big Game were hoping to replicate the success of 2 tech companies that came before them.

HotJobs.com and Monster.com paid for ads in the 1999 Super Bowl, and both reported surges in web traffic during the game.

(Note: There are varying definitions of a ‘startup’ but in this article, we define it as a company that 1) is less than 5 years old, 2) has no corporate parent, and 3) relies on seed/angel funding.)

The Hustle

The 2000 upstarts took a different approach to their ads than Super Bowl mainstays like Budweiser and Coca-Cola.

“Some of the traditional Super Bowl advertisers worked on their commercials for 6 months,” Tim Hanlon, the former senior vice president of LifeMinders.com (the company that created the worst commercial), told The Hustle. “We did it in 6 days.”

“I swear to you, the bar bill was bigger than the production bill,” he said.

The how-to platform Computer.com spent $3m of its $5.8m in seed funding on an ad featuring its 2 founders holding a poster board sign. The site hadn’t even launched yet.

Not all the ads were quite as homespun. Another startup, Pets.com, spared no expense.

According to reporting from USA Today, the company enlisted the “coordinated efforts of 150 people, 40 companies, a 20-piece orchestra, two actors, 12 dogs, cats, turtles, birds, a school of fish, a puppeteer and, of course, one Puppet [the company’s mascot]” to produce its 30-second ad for pet products that featured… a homemade sock puppet.

The ex-Pets.com sock puppet (Youtube/The Hustle)

Skeptics questioned whether the risks would pay off for these unproven brands.

“They haven’t given themselves enough lead time to really do the right thing with the money,” Jeff Goodby, co-founder of Goodby Silverstein & Partners, an ad agency that produced several of the most popular ads in the previous year’s contest, said before the 2000 Super Bowl.

But looking back, Zapolin said he thought success was a sure bet. “A partner and I, we were able to acquire Computer.com the domain name and 1-800-Computers the phone number,” Zapolin told us. “We thought, you know, we have assets like this that are self-explanatory.”

Startups declared an early victory

During the game, Zapolin stood near Joe Namath, John Travolta, and Disney CEO Bob Iger in Disney’s private box and waited to watch himself holding his company’s sign.

Zapolin and company had bought an ad scheduled for the final 2 minutes of the game, when ad execs expected the audience’s attention to wane.

But that year, the game came down to the final play. The St. Louis Rams eked out a last-second win over the Tennessee Titans, 23-16.

Zapolin and Computer.com got what they wanted: Lots of eyeballs.

Mike Zapolin, left, in Computer.com’s $2m Super Bowl ad with co-founder Mike Ford, right (via YouTube)

Zapolin says that Iger turned to him after the ad aired and said: “You must have a horseshoe up your ass because that was the most-watched commercial of all time.”

“Within 24 hours, we had a million-plus people come through the Computer.com site,” Zapolin told us.

But even in the Super Bowl, eyeballs aren’t everything

The real value of that spike in web traffic wasn’t immediately clear. And the rush of attention created a whole new set of problems.

Tim Calkins, a clinical professor of marketing at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, explained to The Hustle that widely seen Super Bowl ads can catch companies unprepared.

“It’s hard to predict exactly how [a successful ad] is going to turn into sales,” Calkins explained. If an ad creates huge demand, “there’s a huge amount of pressure” to fulfill it, he said.

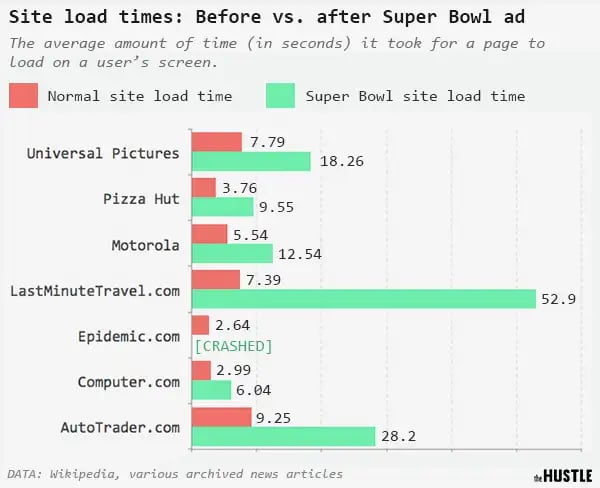

Sure enough, many advertisers’ websites proved poorly equipped to handle the increased traffic.

The Hustle

Computer.com’s site load time doubled during the moments after its ad. One startup’s site slowed from 8 to 53 seconds; another’s altogether crashed.

“Everything was held together with glue and rubber bands,” Hanlon, of LifeMinders, said.

Doug Gould, a professor of the practice of advertising at Boston University’s College of Communication and a former creator of award-winning ads for Anheuser Busch, told The Hustle that follow-up plans are key to Super Bowl success.

Pets.com invested heavily in maintaining post-game momentum, spending $17m on a marketing campaign built around its signature sock puppet the next quarter (the sock puppet appeared on Conan O’Brien’s late-night show months after starring in Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade).

LifeMinders.com hadn’t planned anything that elaborate. The company’s campaign wasn’t fully integrated, like one for Anheuser Busch might be, Hanlon told us.

“In our case, we really just said: ‘Hey, sign up for our email.’”

Upon further review… a reversal

The deflation of the dot-com bubble would have caused problems for these startups no matter what. But the timing made matters even worse for companies that had just placed big bets on the Super Bowl. Eight of the 11 advertisers would soon fizzle out.

Pets.com, whose $17m in marketing resulted in just $8.8m in revenue, declared bankruptcy less than 10 months after the game. Several months later, Pets.com sold off the branding rights to its celebrity sock puppet for $125k.

LifeMinders.com, which had once been valued at $2.3B, had to sell for $68.1m in cash and stock.

Computers.com also sold for an undisclosed amount.

The Hustle

But, according to Zapolin, things would have been worse without the Super Bowl ads.

“Most people got zero — zero — in that dot-com situation,” Zapolin told us. At the very least, the ad gave his company credibility and assets. Those allowed him to pay off some investor notes.

Startups will always be underdogs

In 2000, there were 11 companies under 5 years old that advertised in the Super Bowl. Last year, just 1 company younger than 10 years old (the 5-year-old dating app Bumble) pulled the trigger on Super Bowl ads.

And in this year’s game, there aren’t expected to be any startups advertising.

So are the stories of Computers.com, LifeMinders, and the others proof that startups should never run Super Bowl ads? According to the advertisers and academic experts alike: No.

They all agreed that it’s possible for startups to succeed advertising in the Super Bowl — if they’re strategic about their advertising efforts before, during, and after the game.

“If I wanted to establish myself overnight I would absolutely buy [a Super Bowl ad],” Hanlon told us. “But you’ve got to make sure you have everything working in concert, from public relations to social media, direct, all the activation points.”

The final frame of LifeMinders.com’s “worst commercial ever” (Youtube/The Hustle)

But, while the professors insisted there’s no formula for Super Bowl ad success, they said there are several easy formulas for failure, such as:

- Spending enough money to risk the rest of the business

- Basing an entire marketing strategy on a single ad

- Focusing on branding before building a functional business model

Sound familiar? It should: Their advice for Super Bowl success is simply a good business strategy for any startup, no matter the season.

But for ambitious startup founders like Hanlon and Zapolin, their advice also sounded a bit… safe.

“Analytics are a wonderful tool for marketers, but candidly they create guardrails,” Hanlon told us. “In the case of the Super Bowl this is one of those moments where analytics probably should have a seat at the table but not be at the head of the table.”

Go big or go home

Today, Zapolin is working on a documentary about psychedelic intervention that features NBA star Lamar Odom. Hanlon runs a non-profit dedicated to preserving the cultural heritage of the Apollo landing sites on the moon. And the Pets.com sock puppet is still the mascot of an auto loans company called BarNone.

According to the professors, modern startups are right not to focus on Super Bowl ads these days: For all but a few, it wouldn’t be worth it.

But Zapolin and Hanlon still think more startups can afford to take the risks.

“I think a lot of people are like, ‘shit, well, if one guy misses an execution or this commercial’s not good… I’m going to get fired,’” Zapolin told us. “These entrepreneurs are letting the big guys have all the fun.”

An ad graces the jumbotron during Super Bowl XLVIII at MetLife Stadium in 2014 (Photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

The ads may not have catapulted their startups to success. But they were still risks worth taking, Zapolin and Hanlon said. The spots were funny, clever, and they stood out from the standard fare.

“I remember sitting [in the stadium] and talking to my creative team when we knew the commercial was going to pop up,” Hanlon told us. “I saw all the screens go yellow in the stadium. That was really…”

He trailed off, reminiscing on the magnitude of the moment.

“That was special,” he finally said.

The marketing professors looked back at Super Bowl XXXIV’s defunct startups and saw something else: A lot of startups that fell victim to their own egos.

“Sometimes when organizations run ads, it’s not always for the consumer,” Gould said. The execs want to be seen in the coolest car around, he said, and the Super Bowl is it.

“That doesn’t mean that there’s not business strategy behind it,” he added. “But… there’s ego involved in putting an ad in the Super Bowl.”