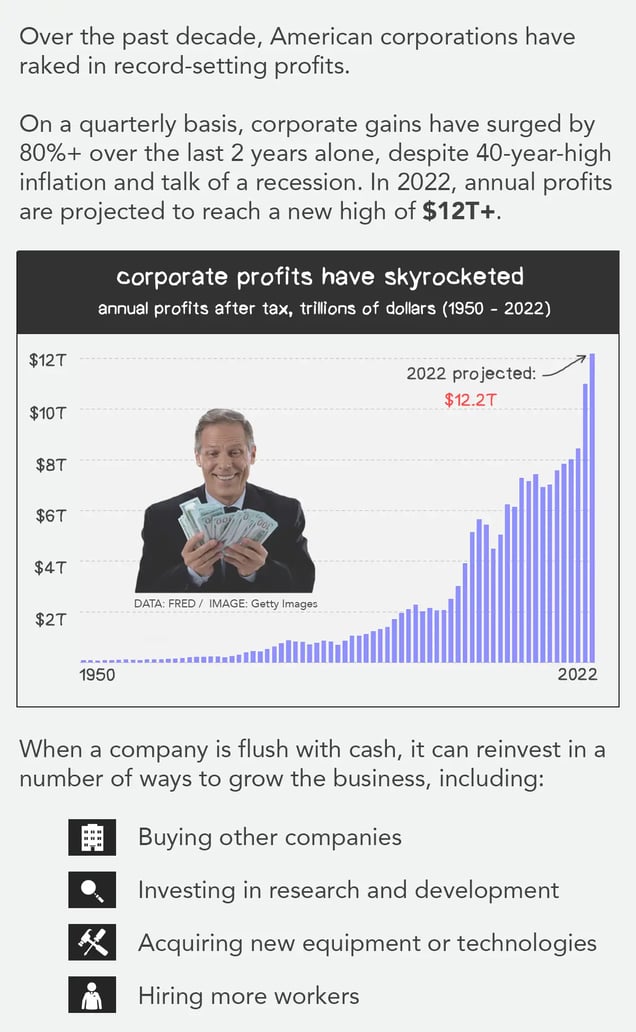

Over the past decade, American corporations have raked in record-setting profits.

On a quarterly basis, corporate gains have surged by 80%+ over the last 2 years alone, despite 40-year-high inflation and talk of a recession. In 2022, annual profits are projected to reach a new high of $12T+.

When a company isflush with cash, it can reinvest in a number of ways to grow the business, including:

- Buying other companies

- Investing in research and development

- Acquiring new equipment or technologies

- Hiring more workers

But in recent times, corporations have been spending their money on something else: Buying back their stock from the open market.

This practice is called a stock buyback, or repurchase:

BUYBACK (n): When a company pays the market value per share to buy back a portion of its ownership that was previously distributed among investors.

For most of the 20th century, stock buybacks were largely illegal and viewed as market manipulation. But in 1982, the Reagan administration instituted a “safe harbor” rule that gave corporate executives broader permissions to use them.

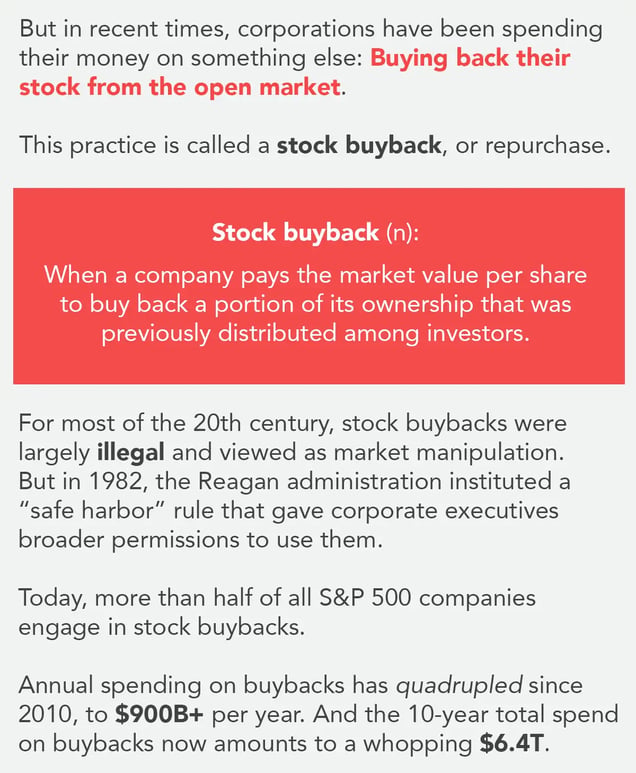

Today, more than half of all S&P 500 companies engage in stock buybacks.

Annual spending on buybacks has quadrupled since 2010, to $900B+ per year. And the 10-year total spend on buybacks now amounts to a whopping $6.4T.

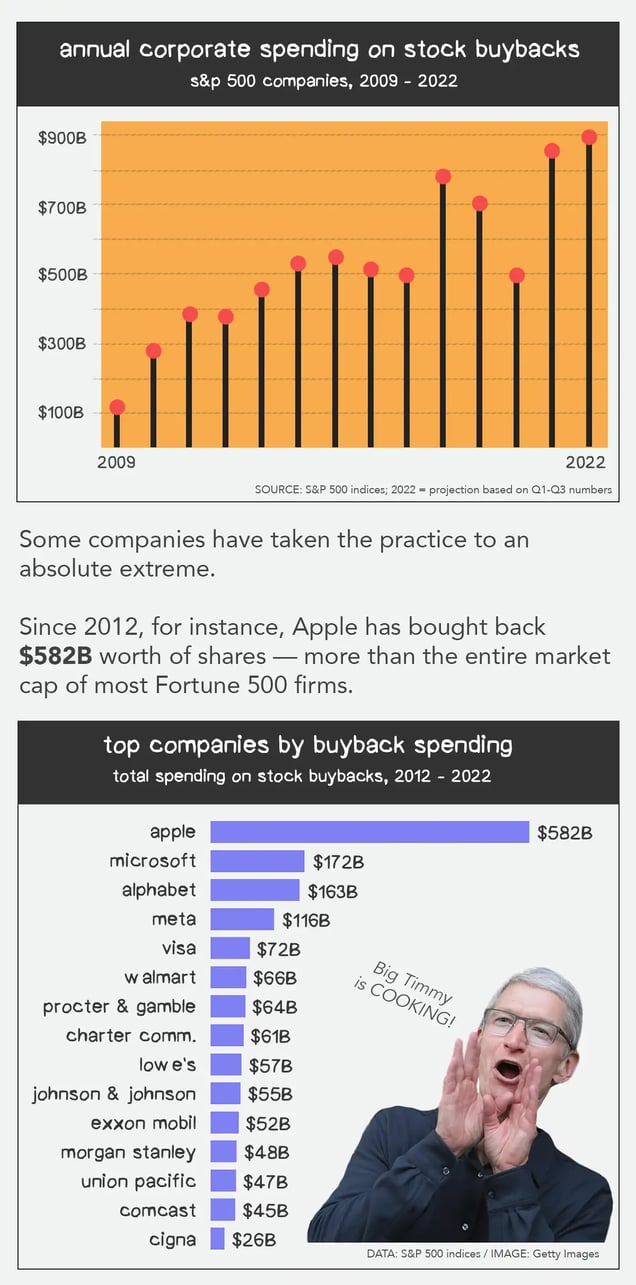

Some companies have taken the practice to an absolute extreme.

Since 2012, for instance, Apple has bought back $582B worth of shares — more than the entire market cap of most Fortune 500 firms. Other top buyback spenders over the past decade include:

- Microsoft: $172B

- Alphabet: $163B

- Meta: $116B

- Visa: $72B

- Walmart: $66B

Why are companies spending so much on buybacks? Proponents make a few claims:

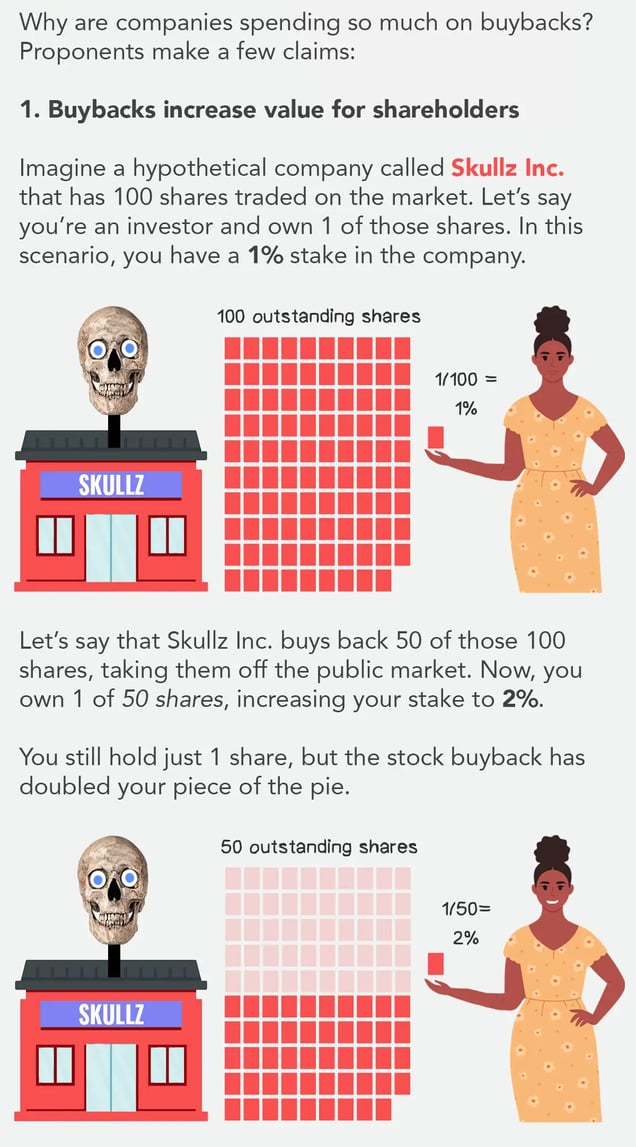

1. Buybacks increase value for shareholders

Imagine a hypothetical company called Skullz Inc. that has 100 shares traded on the market. Let’s say you’re an investor and own 1 of those shares. In this scenario, you have a 1% stake in the company.

Let’s say that Skullz Inc. buys back 50 of those 100 shares, taking them off the public market. Now, you own 1 of 50 shares, increasing your stake to 2%.

You still hold just 1 share, but the stock buyback has doubled your piece of the pie.

Of course, in the real world, companies have many millions of shares. So when stock buybacks happen, the impact on investors is generally much smaller — if there’s any discernible impact at all.

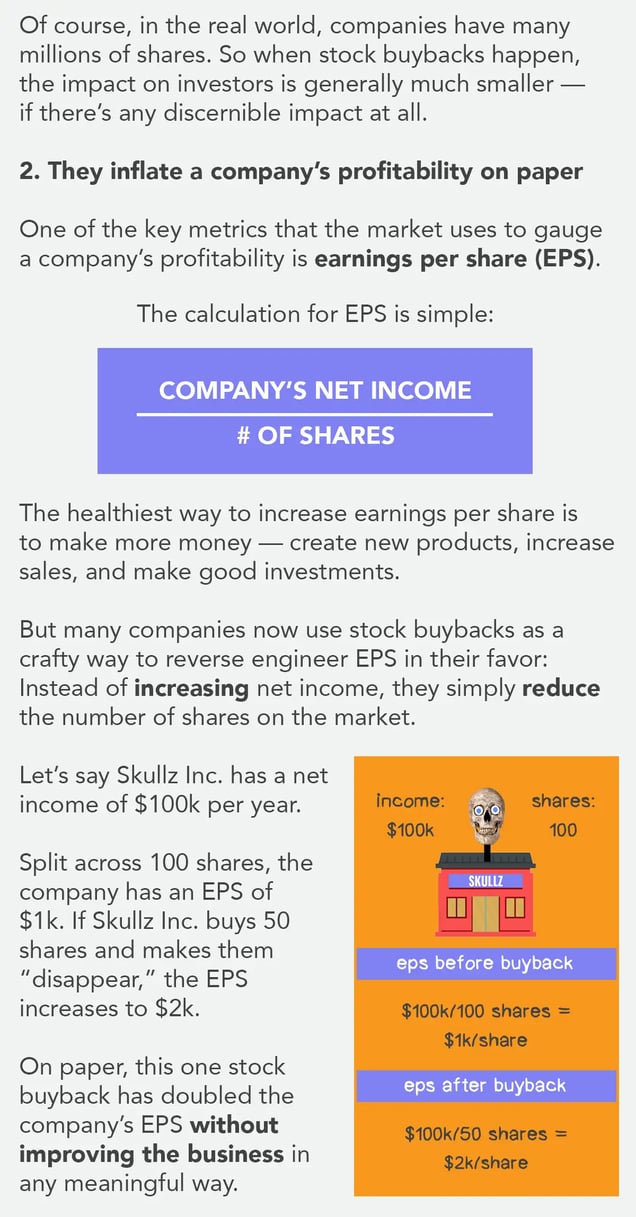

2. They inflate a company’s profitability on paper

One of the key metrics that the market uses to gauge a company’s profitability is earnings per share (EPS).

The calculation for EPS is simple: NET INCOME / # OF SHARES.

The healthiest way to increase earnings per share is to make more money — create new products, increase sales, and make good investments.

But many companies now use stock buybacks as a crafty way to reverse engineer EPS in their favor: Instead of increasing net income, they simply reduce the number of shares on the market.

Let’s say Skullz Inc. has a net income of $100k per year.

Split across 100 shares, the company has an EPS of $1k. If Skullz Inc. buys 50 shares and makes them “disappear,” the EPS increases to $2k.

On paper, this one stock buyback has doubled the company’s EPS without improving the business in any meaningful way.

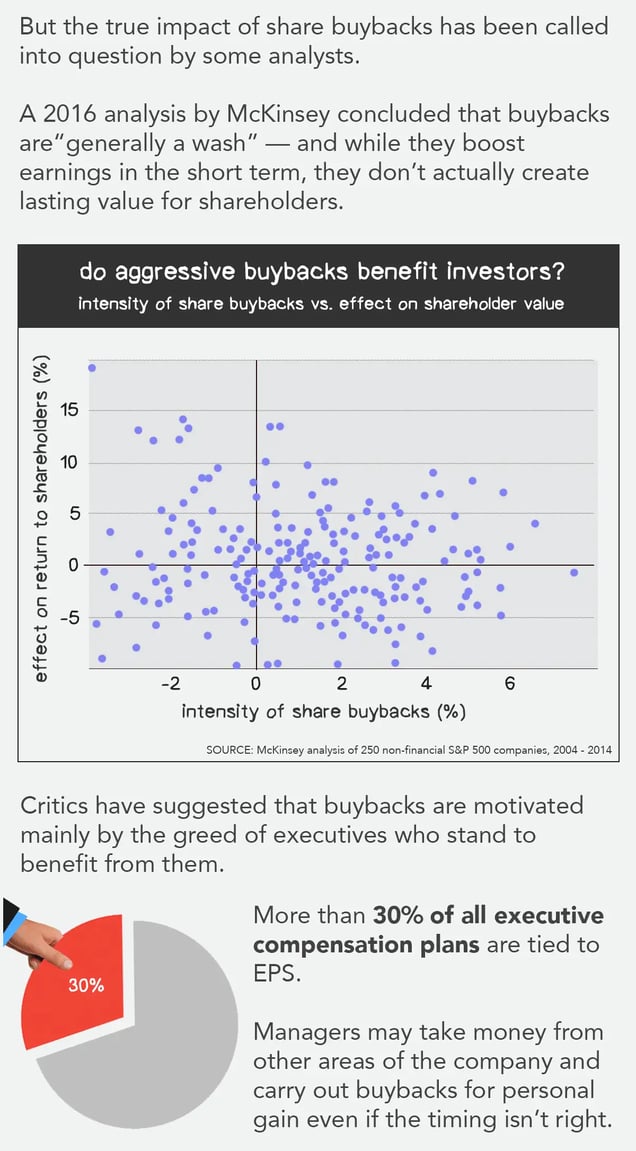

But the true impact of share buybacks has been called into question by same analysts.

A 2016 analysis by McKinsey concluded that buybacks are“generally a wash” — and while they boost earnings in the short term, they don’t actually create lasting value for shareholders.

The dark side of buybacks

Critics have suggested that buybacks are motivated mainly by the greed of executives who stand to benefit from them.

More than 30% of all executive compensation plans are tied to EPS. Managers may take money from other areas of the company and carry out buybacks for personal gain even if the timing isn’t right.

This greed comes with consequences — for long-term success, workers, and the market.

In theory, companies should only do buybacks when:

- They don’t have anything better to do with their cash on hand.

- Prices are low and they can get a better deal on the shares they buy.

But recently, companies have broken those rules.

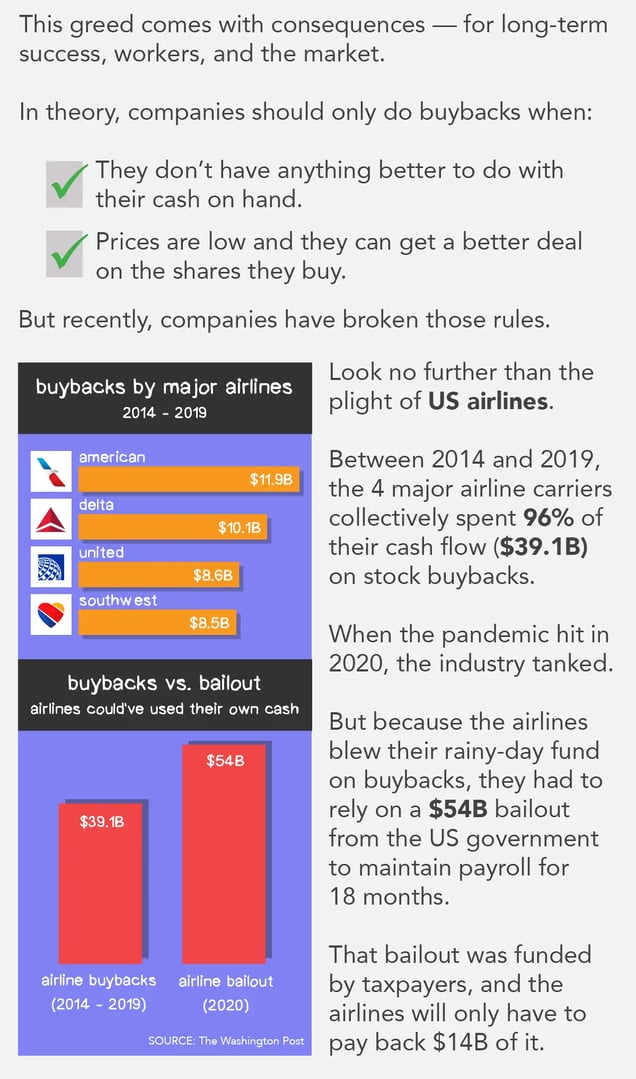

Look no further than the plight of US airlines.

Between 2014 and 2019, the 4 major airline carriers collectively spent 96% of their cash flow ($39.1B) on stock buybacks.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, the industry tanked.

But because the airlines blew their rainy-day fund on buybacks, they had to rely on a $54B bailout from the US government to maintain payroll for 18 months.

That bailout was funded by taxpayers, and the airlines will only have to pay back $14B of it.

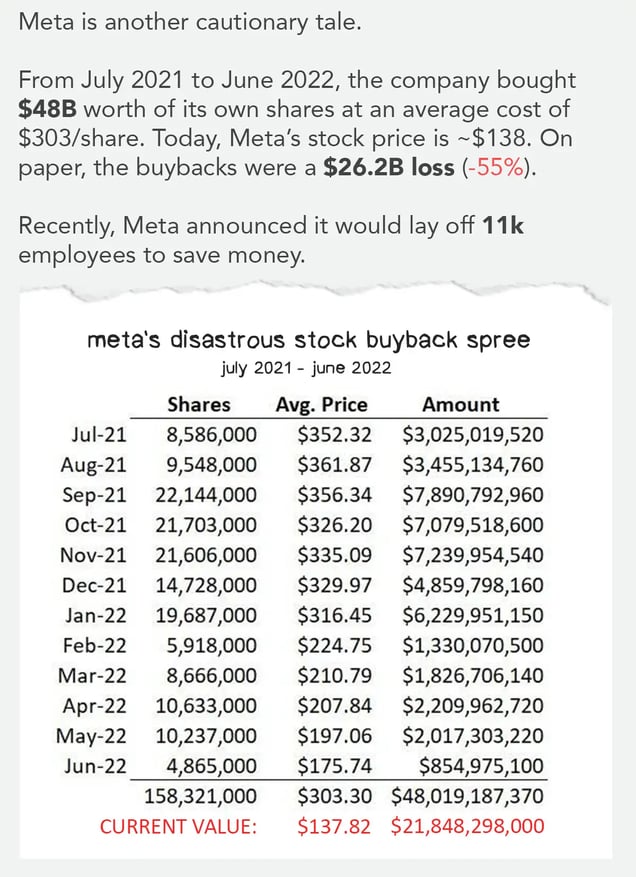

Meta is another cautionary tale.

From July 2021 to June 2022, the company bought $48B worth of its own shares at an average cost of $303/share. Today, Meta’s stock price is ~$138. On paper, the buybacks were a $26.2B loss (-55%).

Recently, Meta announced it would lay off 11k employees to save money.

There are broader concerns with stock buybacks.

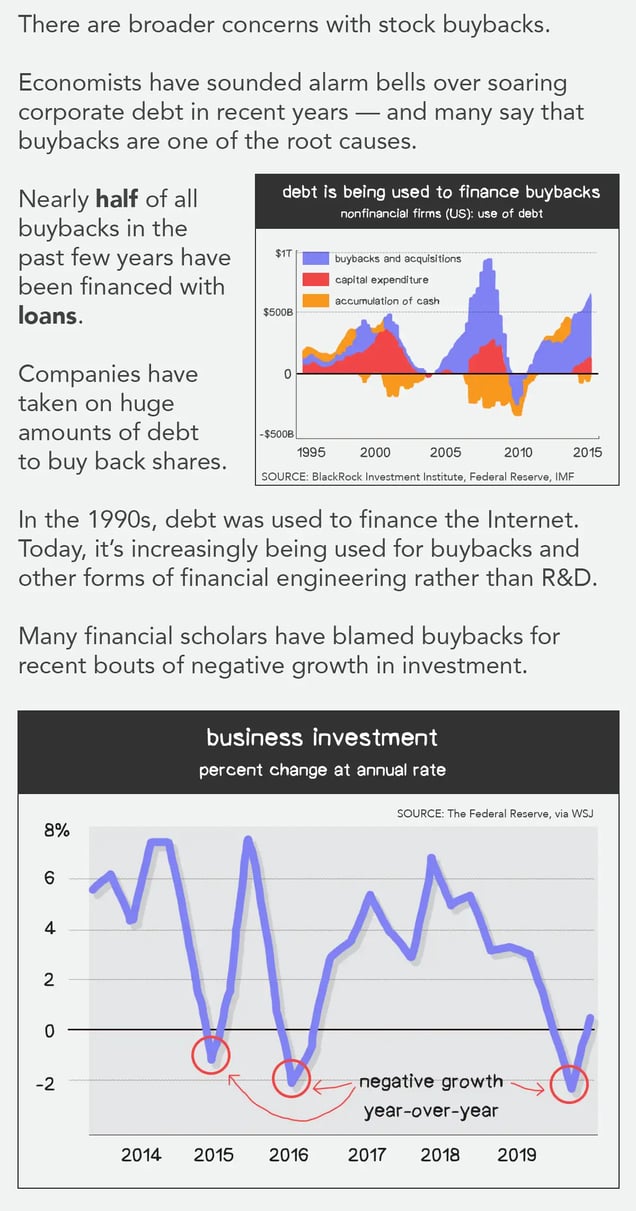

Economists have sounded alarm bells over soaring corporate debt in recent years — and many say that buybacks are one of the root causes.

Half of all buybacks in the past few years have been financed with loans. Companies have gone beyond their own cash reserves and have taken on huge amounts of debt to buy back shares.

This has come at the expense of real, long-term business investments and expansions.

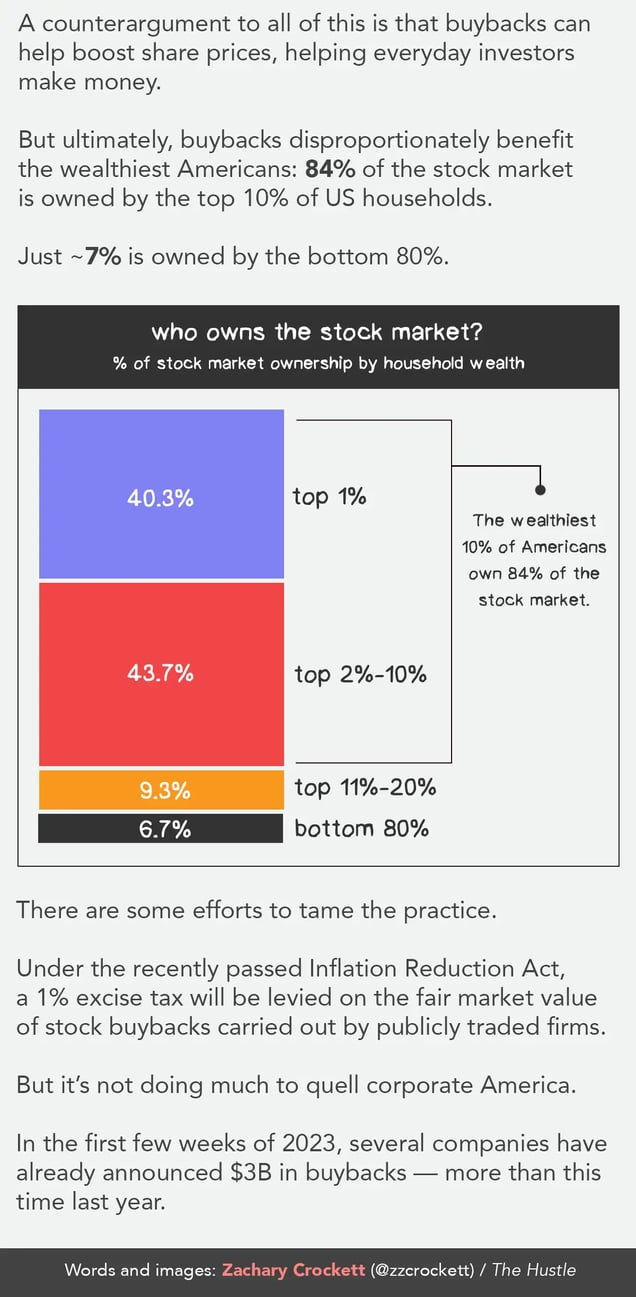

A counterargument to all of this is that buybacks can help boost share prices, helping everyday investors make money.

But ultimately, buybacks disproportionately benefit the wealthiest Americans: 84% of the stock market is owned by the top 10% of US households.

Just ~7% is owned by the bottom 80%.

There are some efforts to tame the practice: Under the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act, a 1% excise tax will be levied on the fair market value of stock buybacks carried out by publicly traded firms.

It’s not doing much to quell corporate America.

In the first few weeks of 2023, several companies have already announced $3B in buybacks — more than this time last year.