If Uber’s 2017 were a ride across town, it would get 1 star.

You’d be hard-pressed to dredge up a worse 12-month stretch in recent corporate history. It seemed like every week, the rideshare giant would grapple with a flat tire:

- Allegations of systemic sexual harassment and sexism.

- Losing 400k customers in the wake of the #deleteuber hashtag on Twitter.

- Getting called out by their own investors for having a “toxic” culture.

- A federal lawsuit over the IP theft of self-driving car technology.

- A video of Uber’s then-CEO, Travis Kalanick, berating one of his company’s drivers for not “[taking] responsibility for [his] own sh*t.”

- Losing $1B in a largely unsuccessful bid to compete in China, and…

- Kalanick’s ultimate resignation.

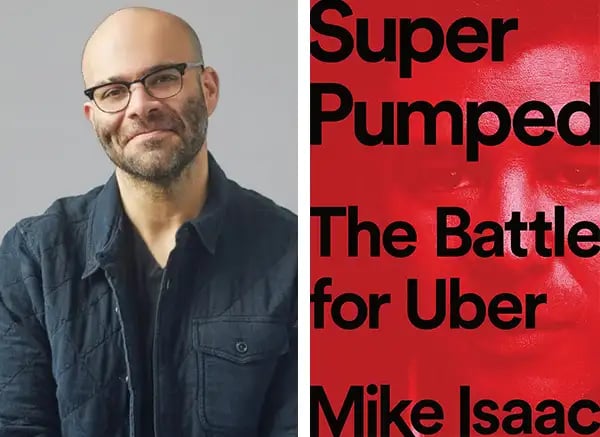

Mike Isaac, a reporter at The New York Times, was along for the whole ride — and he’s chronicled it all in his new book, Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber.

I recently spoke with Isaac about the company’s tumultuous journey to the top, and how it serves as a cautionary tale for the tech industry at large. The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Can you tell me a bit about the scope of reporting that went into this book?

I first started following Uber in 2010, when it was still called UberCab. It’s been nearly 10 years in the making of being around this company, watching it grow and change, and seeing how [Silicon Valley] evolved around it.

Why is Uber’s saga important to rehash right now?

We’re at a very interesting and new time in technology. There was an inflection point in 2016-2017 where people really started to question how tech shaped their lives. The election of Trump called into question how these big platforms, like Facebook and Twitter, might be manipulated.

In the wake of that, Uber stepped in and became this avatar for everything that seemed to be wrong with tech.

There’s the Wolf of Wall Street-level excess in terms of wealth and opulence — from raising enormous amounts of money to spending $25m on a single [employee] party in Vegas in 2015. There’s the conversation about how they treat drivers, and the divergence of different class structures — the people who use the service, and the “underclass” who serves them. Then, there’s the all the bad behavior that results from growing at any cost.

The book is about Uber, but it’s also kind of not about Uber. It’s more about the way that perverse incentives can make good people do bad things, and make bad people do even worse things.

Let’s talk about the “growth or die” mentality that Uber, like many startups, adhered to. What darker paths did this lead Uber down?

In 2017, there was a rash of extreme violence in different countries [where Uber’s service was expanding].

Outside of Mexico City, in cartel country, there were drivers being killed. In Brazil, drivers were getting robbed and murdered. Some of these instances were the direct result of not building enough safeguards into the app to verify riders’ identities. But it was really about signing people up with as little friction as possible, as fast as possible.

The thing they didn’t realize — and this applies to most tech companies — is that parachuting into markets with their own cultural and socioeconomic factors and dropping a new thing in can have a lot of different consequences. Some of those are good, like allowing people to earn more than they did before. Others are wildly crazy, and wrong, and bad.

Uber’s growth strategy also relied heavily on breaking rules. As you reported, they’d launch in a new city and just straight up ignore all the local laws. One source even told you there was an attitude that “the law isn’t what’s written; it’s what’s enforced.”

Right. Uber saw themselves as a new entry into an inherently unfair system that was set up for [the taxi industry] and wasn’t open to competition. They thought that this system didn’t allow room for others to break in; it was like, the rules don’t really matter when they’re bullshit to begin with.

[Uber’s] response to that was not to change the system from within but to blow up the system and try to ‘invade’ cities. Their strategy was to get to the point where their service would become so indispensable that the legislature would just have to deal with them. Their disruption would lead to new laws. Most of the time it worked.

I do wonder what entrepreneurs will take away from that. Maybe they’ll try to replicate it. Hopefully not.

Uber, of course, did a lot of things wrong. But you write that their story shows both the best and the worst of Silicon Valley. Can you parse out this duality a bit?

It’s too easy to say tech is evil, or to become a Luddite and want to destroy it all.

A lot of the things these companies build can be used as a positive force. I just think you really have to look hard at the negative influence to help curb that, whether that’s people being killed, or drivers having to sleep in their cars [due to inadequate pay]. Are we willing to live with these things as a cost of doing business, or should we work together to figure out a better way of doing things?

Right now we’re in an era of regulation. So we’re starting to rein in the unfettered power of tech.

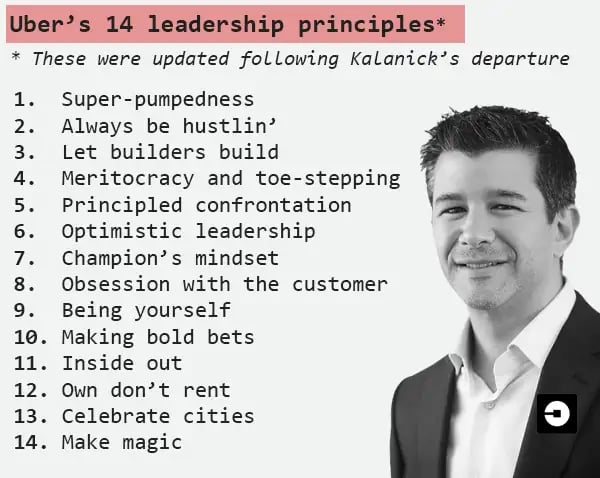

What did the term “super pumped” mean to employees there?

Being “super pumped” was actually one of the values employees were evaluated on for their official job reviews. Managers would review them on their level of being super pumped. Kalanick wanted everyone to be “super pumped”… being super pumped gave you super powers.

It embodied what their mentality was — this sort of bro-ish ideal of excitement and a willingness to take on everyone.

Kalanick also loved the word “hustle.” In fact, “Always be hustlin’” was one of his 14 core values. What did this word mean to the company culture?

At Uber, people would get emails at all hours of the night. If you didn’t respond at midnight, you’d get [flak]. People I talked to said there was very little work-life balance.

My colleague, Erin Griffith, wrote a really good feature on “hustle culture,” and this idea that you always need to be working.

You write in the book that Kalanick hated to lose. Winning wasn’t enough; he had to crush his competition. Do you see him as a Machiavellian figure?

There were a few comparisons that kept coming up when I talked to people [about Kalanick]: Machiavelli. Sun Tzu. Some people called him a Trumpian figure, in the sense that he was great at creating his own reality.

But Machivelli really fits. [Kalanick] had a very cynical, dry, almost militaristic view of the world — a kind of moral relativism predicated on the idea of winning and conquering.

Who where Kalanick’s chief enablers?

He tended to hire people who worshipped him or idolized him. Investors just wanted to make money, so they didn’t really care if the culture was terrible.

Investors also contributed to a “cult of the founder” in Silicon Valley: They gave celebrity CEOs free rein to do as they pleased. Was this mentality partly to blame for Uber’s eventual leadership problems?

Investors certainly reinforce this cult of the founder.

They’re looking for that next Zuckerberg or Spiegel — a wünderkind who can build the next billion-dollar startup in their dorm room while eating bowls of ramen. It’s a very attractive mythology. The idea of fetishizing this boy genius figure was common for a very long time; now, we’re nearing the limits of that.

So much can go wrong when you give one person unfettered control of a whole company — really, control over changing a lot of what the world looks like. And a lot of it starts at the investment level.

Do you think a certain ruthlessness is necessary in building a huge tech company like Uber? Is the power inherently corrupting?

The usurper always ends up being the dominant culture. The people who come in wanting to free society from the bondage of power end up having the power — and maybe abusing that power.

One of [Kalanick’s] flaws was the inability to recognize when he won, when he was that great company. He viewed Uber from the lens of a scrappy startup, but then one day, he was the guy at the top. And tech leaders will do what’s necessary to stay at the top.

There are so many shocking anecdotes in your book, from Uber execs expensing strip club visits to Kalanick turning down a $40m investment from Jay-Z. Of all the things you reported on, what shocked you the most?

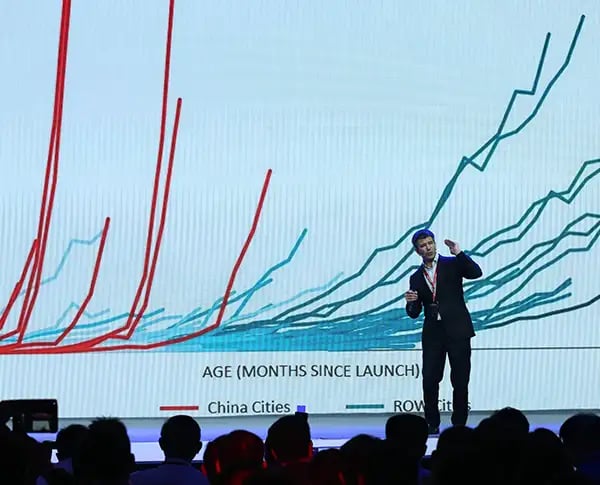

The scale of Uber’s fraud in China was insane to me.

I talked to sources who told me that literally half of all dollars in some cities were going to completely fraudulent rides from scammers, who ended up building a huge crime ring around Uber. The lengths to which they went to to build some of these systems was staggering.

I imagine investors would not be too happy if they knew their money was going straight into the incinerator, or the pockets of criminals in China. In Southeast Asia, [Uber] went from 70-something market share to 20 and burned through piles of money.

It’s been two years now since Kalanick was ousted. How have things changed at Uber since then?

It’s going to take them a while to repair their reputation — if they even can. They’re still reconciling with all the things in their past.

Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber is available on Amazon now.