On January 25, 1979, a 25 year-old factory worker named Robert Williams scaled a storage rack at the Ford Motor Company’s Flat Rock Casting Plant.

One of three workers in the parts retrieval system, he was tasked with overseeing an industrial robot — a one-ton, 5-story mass of gears that transferred car parts from the shelves to ground level.

That night, the bot gave an erroneous inventory reading, and Williams was forced to ascend on his own. He never made it: Halfway up, the robot struck him from behind, crushed his body, and left him to die high above the factory floor.

It was the first time in recorded history that a robot killed a human, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Over the past 25 years, 61 robot-related injuries and deaths were reported in the US. The vast majority of them were caused by industrial robots, like the one that killed Robert Williams. But what happens when a robot goes rogue? And who is to blame?

When robots kill

In 1942, sci-fi legend Isaac Asimov laid out what would come to be known as the Three Laws of Robotics, or Asimov’s Laws — a set of principles robots should follow in the future:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Unfortunately, the first rule has been broken many times over.

In a factory setting, robots are intended to “perform unsafe, hazardous, highly repetitive, and unpleasant tasks.” As a result, bots often don’t have the intelligence to detect humans outside of programmed tasks.

Add to this the fact that there are currently no specific workplace safety standards for the robotic industry, and you’ve got a disaster waiting to happen.

Often, these deadly interactions occur when a robot has a mechanical (hardware) issue and needs human intervention — but the machine lacks the software intelligence to tell a human apart from a pallet, a box, or some other item it is programmed to grip, crush, and/or annihilate.

We went back through news archives, court documents, and OSHA reports and found a number of cases (both in the US and abroad) where the action of a robot (or the misaction of a related safety mechanism) seemed to be at fault for a worker’s death. A few examples:

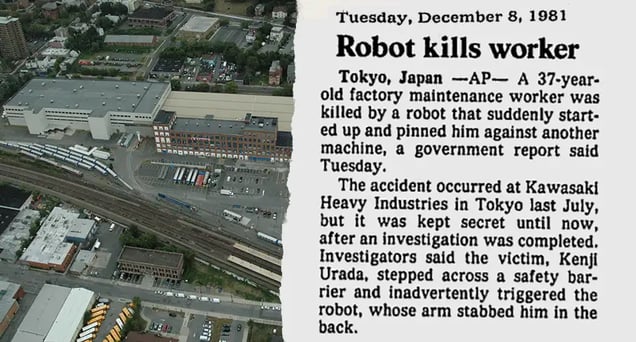

Robot inadvertently turns on (July 4, 1981)

Who: Kenji Urada, 37-year-old maintenance worker

Where: Kawasaki Heavy Industries plant (Akashi, Japan)

What happened: When a robot in Kawasaki’s state-of-the-art facility malfunctioned, Urada opened the safety barrier (an action that should’ve automatically powered down the machine), and attempted to fix the issue. The robot turned back on, stabbed Urada in the back with its arm, then crushed him.

An investigation found that many Japanese factories had a “tendency to put aside regulations” when it came to exciting new robots. The offending machine was removed from the factory and more secure fences were erected.

Robot fails to sense human presence (July 21, 2009)

Who: Ana Maria Vital, 40-year-old factory worker

Where: Golden State Foods (Industry, California-based meat supplier)

What happened: Vital was overseeing a palletizer robot, a giant machine that stacked boxes. A box become stuck, and Vital entered the robot’s “cage” to pull it out — but when she did, the robot mistook her for a box and grabbed her, crushing her torso. The robot had supposedly been equipped with sensors to differentiate humans from boxes, but they had failed.

Robot goes “rogue” (July 7, 2015)

Who: Wanda Holbrook, 57-year-old factory technician

Where: Ventra Ionia (Ionia, Michigan-based auto assembly factory)

What happened: Holbrook was fixing a piece of machinery when a factory robot went “rogue.” According to a lawsuit, the robot’s arm “took [Holbrook] by surprise,” entered the section she was working in (against programming commands), and “crushed her head between a hitch assembly it was attempting to place.” She died 40 minutes later.

In 2017, Holbrook’s bereaved husband filed a wrongful death complaint blaming 5 engineering firms involved in building, testing, and maintaining the robot; it is currently inching its way through the court.

Who is to blame when a robot kills?

Most of the time a robot kills a human, it’s because the bot is too stupid, not too smart. As such, blame (on the grounds of negligence) is typically placed on the machine’s manufacturers.

In the case of Robert Williams, for instance, a jury found the robot’s manufacturer, Litton Industries, at fault, and the worker’s family was awarded $10m. (The final amount was eventually settled out of court, in exchange for Litton not admitting to negligence.)

But as artificial intelligence progresses and bots become more than just hardware following computer code, the blame game will get a lot more complex. Legal scholars are currently engaged in a “furious debate” over whether or not robots could hypothetically be charged with murder.

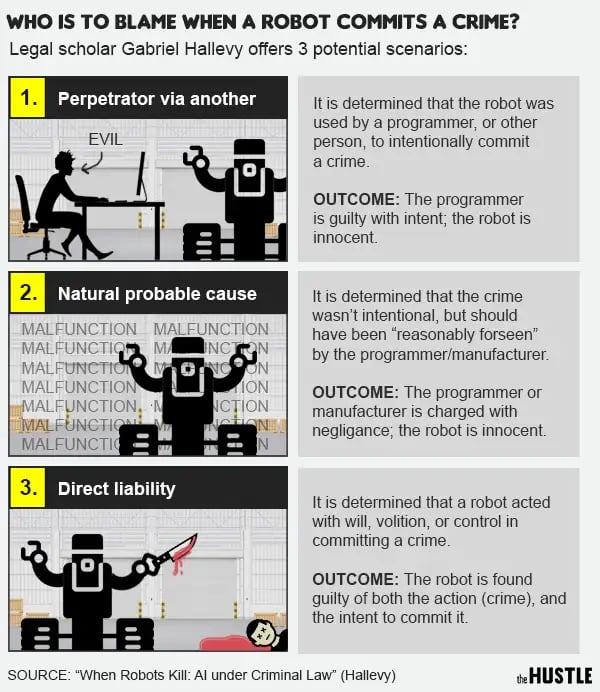

Gabriel Hallevy, author of When Robots Kill: Artificial Intelligence under Criminal Law, has extensively studied the topic, and has proposed changing criminal law to hold “non-human entities” (AKA robots) liable for crimes, similarly to corporations.

In most countries, criminal liability entails two components: 1) An action, or the crime itself, and 2) Mental intent, or awareness of the crime.

Robots have stabbed, crushed, electrocuted, and strangled factory workers — so we already know that they’re capable of committing the action. But what about the awareness?

“In criminal law, the definition [of awareness] is very narrow,” Hallevy told the Washington Post in 2013. “It is the capability of absorbing sensual data and processing it… to create an internal image.”

Machine learning (a subset of artificial intelligence) strives to empower robots to do just that: by feeding a robot large swaths of data, we hope it may learn to process it on its own. In a future where industrial machines have the ability to make their own decisions in this manner, robots could feasibly be charged with the intent to murder..

Relax, robots aren’t evil murderers… yet

Machines are gaining autonomous agency at an rate that has been compared to a 4th Industrial Revolution. And every time something goes wrong — whether it’s a self-driving car death or a surgery mishap caused by an operating smart bot — it makes for a sensational national headline, regardless of who was at fault.

Our fears of robots have always centered around them gaining too much intelligence: Sci-fi writers have harped on the dangers of sentient killer bots. Tech luminaries like Elon Musk and Bill Gates have donated millions of dollars to research the risks of AI. Every time a Boston Dynamics machine does a backflip, the internet bemoans the end of humankind.

But occasional stories of robot-related deaths, though grisly and sensational, should not suggest that robots are some evil, murderous scourge.

The point here is that most robot-related incidents thus far have been the result of: 1) Machines being too stupid, rather than too smart, or 2) A disharmonious relationship between man and machine. For better worse, AI is poised to change both.

As a founder of the research firm ATONATON, Madeline Gannon has been working on improving communication between man and machine, a job that’s earned her the title of “robot whisperer.”

In one video, she stands before an enormous, orange robot arm, using motion capture markers to control its movements. It follows her hand like a charmed snake — and for a moment, it’s easy to forgot this machine is capable of crushing a human skull. It’s no longer a “thing,” but a live, dynamic creature.

Soon, she tells The Hustle, machines like this will leave the lab and “live in the wild.” And time will tell if they decide to play nice.