The Smiley Company office in London, England, is a wonder to behold.

Smiley paintings line the walls. Smiley push pillows adorn the couches. There are smiley backpacks, smiley t-shirts, smiley exercise balls, smiley toys, smiley chocolates, and even smiley chicken nuggets.

This simple icon — a yellow circle, two dots, a smile — retained relevancy through 50 years of cultural movements, from free love to raves to the digital revolution.

And in the process, it became a family-owned global licensing empire worth more than $500m per year. But how did it get there?

Will the real smiley inventor please stand up?

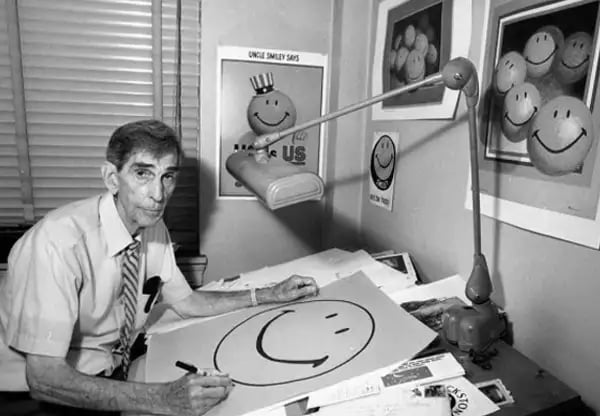

In 1963, a Worcester, Massachusetts-based freelance artist named Harvey Ball received a life-changing call from a local client.

State Mutual Life Assurance Company had just merged with an out-of-town competitor, and employee morale was waning. They needed some kind of quirky and fun design to lift spirits around the office.

It took Ball 10 minutes to produce his famous solution: A bright yellow circle with black oval eyes and a creased smile. For his work, he was paid a one-time fee of $45 ($376 in 2019 dollars).

By most accounts, this was modern history’s first “smiley face.”

It wasn’t, of course, the first: Crude versions of the simple design have since been found painted on 4,000-year-old Turkish pottery, engraved in medieval stones, and scribbled in 19th-century letters.

Ball’s iteration, however, struck a chord, ushering the smiley into mainstream American culture.

Others were quick to pounce on the icon’s popularity. In Philadelphia, two Hallmark card shop owners printed it on buttons, along with the phrase, “Have a Nice Day.” The brothers, Bernard and Murray Spain, sold 50 million of them during the height of the Vietnam War.

It soon became clear that Ball’s simple illustration was worth millions of dollars. But he’d made a critical mistake: He never filed a trademark.

The man who owns the smiley

Halfway across the world, in Paris, France, a young journalist named Franklin Loufrani had his own stroke of invention.

Loufrani had foregone college and joined his first newspaper at 19 with little formal training. But according to those who knew him, he was an entrepreneurial spirit — a “marketing guy who was always coming up with new stuff.”

In 1971, while working for the paper France-Soir, he became fed up with the constant stream of negative news and decided to design a symbol that would alert readers of positive stories.

His creation, a smiling yellow face, bore a striking resemblance to Ball’s.

But unlike Ball, he foresaw the symbol’s marketing potential and immediately secured a French trademark.

“You could say there was a political or social meaning behind what he did, but it was really a commercial act,” Loufrani’s son, Nicolas, told The Hustle. “He wanted to make money on it.”

Trademark secured, Loufrani set out to license the living daylights out of his new icon.

Licensing, or allowing other businesses to use your logo in exchange for a percentage of every sale, wasn’t a very popular business model in Europe at the time. Loufrani was among the earliest to venture into the space — and at first, it was a hard sell.

After it ran in the France-Soir in January of 1972, a smattering of other newspapers paid to use it. But Loufrani realized he had to get the word out on a wider scale to attract a diversity of industries.

In his words, he had to “tap into a movement.” Luckily, there was one happening in the streets.

The free love smiley

In the early ‘70s, France was emerging from a counter-cultural movement similar to America’s hippie uprising: Students were rejecting moral strictures, embracing free love, and leaning into a sexual revolution.

Loufrani printed the smiley onto 10 million stickers and handed them out for free. The icon’s simplistic joy played into the movement and was soon plastered on car bumpers all over the country.

As it trickled into mass culture, brands came knocking.

Two years into his trademark, Loufrani secured a lucrative partnership with the candy company Mars, which printed the smiley face on its chocolate Bonitos (the forerunner to M&Ms in Europe).

Other big licensees were soon to follow: Levi’s rolled out smiley-emblazoned jeans; Agfa (a German film giant) packaged its film in smiley-branded boxes; stationery retailers pumped out smiley journals, notebooks, and pencils.

“It wasn’t controlled — the product aligned with the movement naturally,” says Nicolas. “My father realized early on that instead of fighting for control over how people saw it, he should ride the wave of culture.”

This tactic wasn’t welcomed by Loufrani’s traditionalist peers. “They would say, ‘Hippies are dirty! Why would you associate with that?’” adds Nicolas. “But [my father] didn’t care. He welcomed it.”

Raves, drugs, and smileys

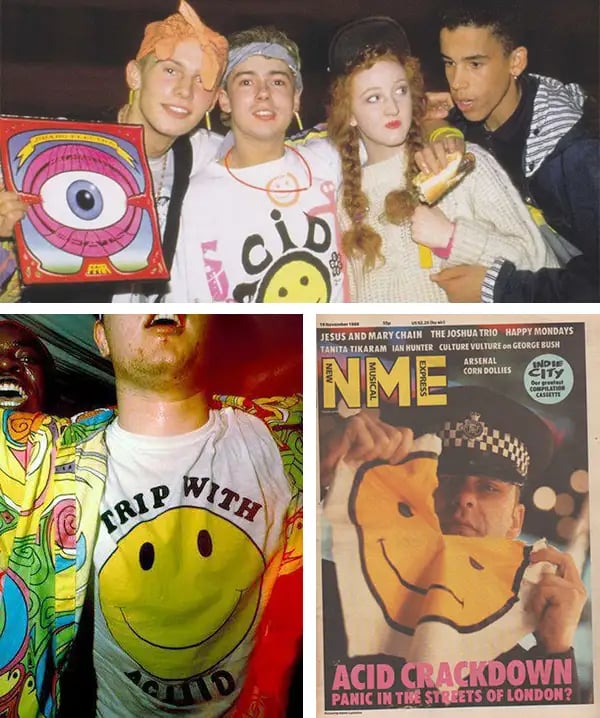

In the 1980s and early ‘90s, the smiley was adopted by a new generation of ecstasy-fueled ravers.

This began naturally, with early electro DJs like Danny Rampling using the logo on fliers for parties — and once Loufrani sensed this new culture embracing his symbol, he capitalized on it.

He reached out to DJs, stayed on top of all the trends, and hit the clubs, selling t-shirts and buttons. Simultaneously, this new market drove licensing deals with trendy apparel companies.

But as the rave movement grew, so too did an anti-rave movement led by traditionalists. The smiley, by association, was cast in a dark light: It was no longer just an innocent happy face; it was a symbol of rebellion.

“They were using smiley faces to show how bad rave culture was. They’d hold up a smiley and say, ‘This is criminal!’” says Nicolas.

While other licensors fought for strict control over how their logos were used, Loufrani set the smiley free and let it ride the tides of cultural movements.

“He didn’t fight the adoption of the logo into something else,” says Nicolas. “My father didn’t care. He’s never cared about how people think. He is an unconventional person who always wants to try new things.”

The smiley goes digital

By 1996, the smiley business wasn’t looking so hot. Licensing deals were down, and the logo was starting to lose its edge.

Loufrani, who was aging, tapped then-26-year-old Nicolas to head operations. “I wasn’t excited about it,” says Nicolas. “I thought it was old and lousy, something that was passed.”

Though his father had been in business for 25 years, the smiley was “strictly a licensing play,” Nicolas says. There was no brand name, no company — just a logo.

“In the US, people would call it a ‘happy face.’ In France, it was a sourire. In Japan, it was a ‘peace love’ mark,” says Nicolas. “Every country had a name for it, so I decided, okay, we need a brand.”

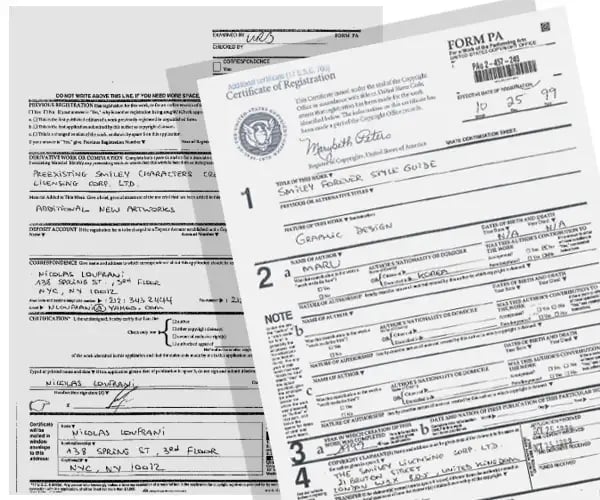

Nicolas formed The Smiley Company and secured trademarks for the ‘smiley’ brand name in 100 countries around the world. In countries where it was taken, the Loufranis bought it, or battled the owner in court (including a famous, 10-year legal battle with Walmart in the US).

Then, against the wishes of his father, Nicolas made major updates to the old-school smiley face, morphing it from a static image to a 3D orb. He dubbed it the “new smiley.”

“It was totally against all marketing theory: If you have a logo, you don’t create new ones,” he says. “My father was furious. He said, ‘It’s stupid what you’re doing! You have a trademark! Keep the logo, but don’t change it!’”

But Nicolas sensed a larger shift happening: The rise of the internet and mobile technology.

Though people had been using text-based emoticons — 🙂 😉 🙁 — as early as 1982 (computer scientist Scott Fahlman was thought to be the first), Nicolas anticipated a future where people would use real smiley icons to communicate.

In 1999, he rolled out more than 470 iterations — what are purported to the first-ever set of portrait-orientation emoticons.

“We had winky smileys, angry smiley, animal smileys, fruit smileys, flag smileys, Statue of Liberty smileys…there was a smiley for everything,” says Nicolas.

Under The Smiley Company brand, he launched SmileyWorld — a universe containing all of his new creations — and licensed them to mobile companies like Nokia and Samsung. In 2001, The Smiley Company’s slogan became “The birth of a new universal language.”

Soon, tech companies like Apple and Microsoft come out with their own sets of proprietary emoticons.

But as emojis became a part of a new everyday language, The Smiley Company saw residual benefits in its licensing business: It rolled out partnerships with push toys, games, food companies, fashion retailers.

“When emojis started to pick up, we were seen as the originator, and it gave us a renewed credibility,” says Nicolas. “The smiley was cool again.”

The money machine

Today, Nicolas and his father, now 76, still run the business together.

The Smiley Company does nearly $500m per year in licensing deals, working with companies like Nutella, Clinique, McDonald’s, Nivea, Coca-Cola, VW, and Dunkin’ Donuts.

Though royalty fees vary based on the size and scope of the company, they can be as high as 10% of what an item sells for. Based in London, the Loufranis and a staff of 40 constantly scour the market for up-and-coming trends, then mock up smiley concepts and pitch them to brands.

They work with more than 300 licensees across 12 major categories, ranging from smiley-branded gummies to smiley-branded Rubik’s Cubes.

Though Loufrani can be credited with the commercial spread of the smiley face, he often faces the criticism that he merely took another man’s creation and made it popular — an idea he dismisses.

“When it comes to commercial use, registration is what counts,” he told The New York Times in 2006. “I hit the casino jackpot.”

And what of Harvey Ball, the Massachusetts artist widely acknowledged to be the true father of the smiley?

He passed away in 2001, at the age of 79, having never profited off the smiley beyond his original $45 payment. But he died with no regrets; for him, the smiley had served its purpose.

“He was not a money-driven guy,” Ball’s son told the WorcesterTelegram & Gazette shortly after he passed. “He used to say, ‘Hey, I can only eat one steak at a time.’”