This summer at the local gas station in Tabor, Iowa, Stacey Rycroft and her husband reached an undesirable milestone: $100 to fill the tank of their Chevrolet Traverse.

“It’s a pretty high level of frustration,” Rycroft told The Hustle.

That frustration has been palpable everywhere. With average US gasoline prices reaching a peak of $5.19 in June and currently hovering at ~$4, Americans have canceled vacations, reconfigured commutes, and plastered gas stations with stickers blaming Joe Biden.

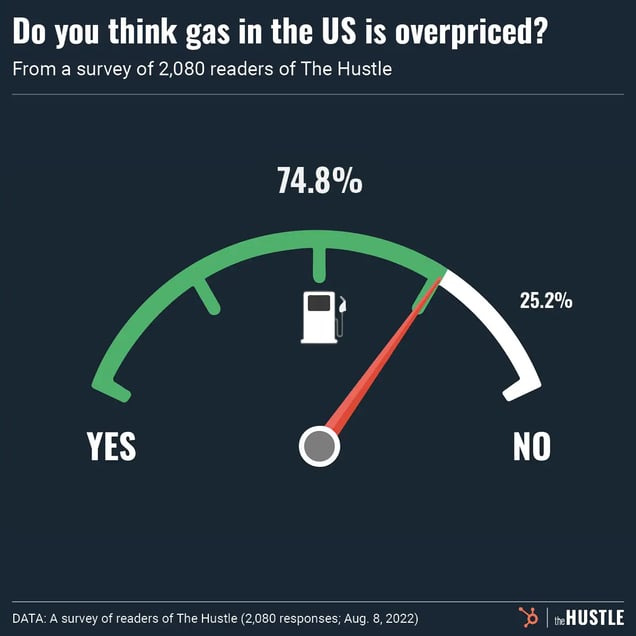

In a recent survey run by The Hustle, 75% of respondents said they thought gas was overpriced in the US.

Singdhi Sokpo / The Hustle

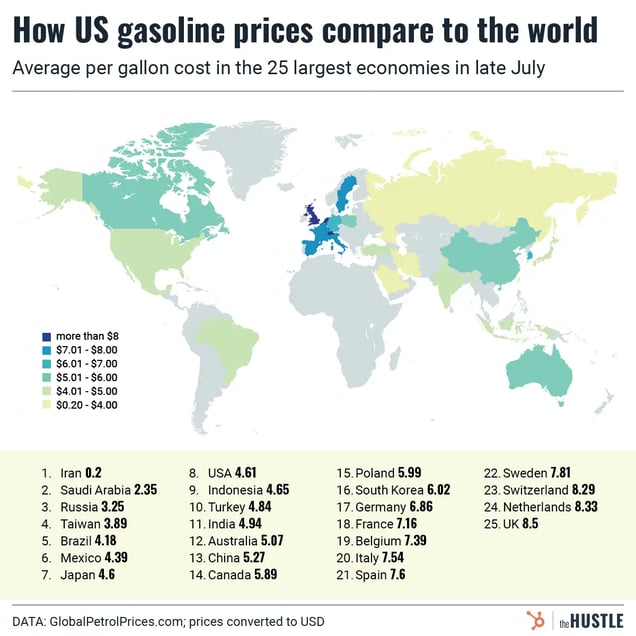

But there is a surprising truth amid the inflation: Compared to other large nations, gasoline in the US is actually extremely cheap.

Countries game the consumer cost of gasoline through taxes and subsidies, leading to wildly different prices around the globe. In the US, prices are far lower than most large economies because of comparably light taxes at the federal and state level.

“It’s been a priority of the public for decades now to have inexpensive fuel and gasoline,” said Garrett Golding, senior business economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

As hard as it is to think about during an expensive summer, the US faces a gasoline tax dilemma: The relatively cheap gas Americans rely on comes with heavy, hard-to-solve costs for the public.

All about the taxes

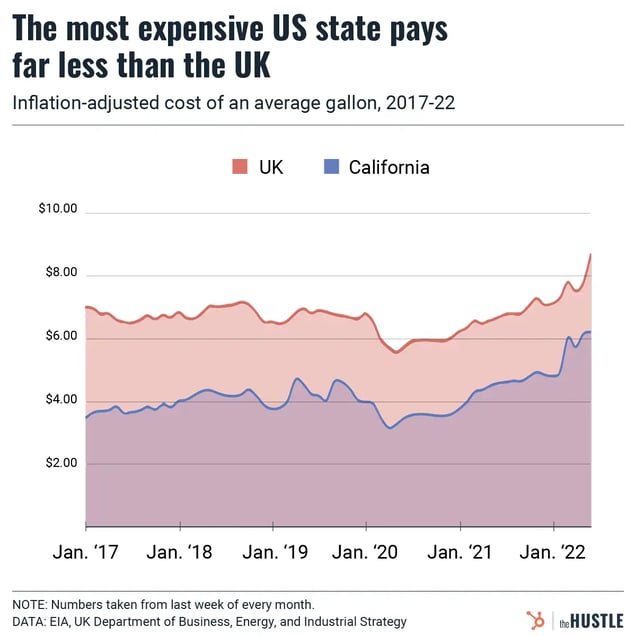

Back in late July, while gas was ~$4.61 at the pump in the US, things were far worse in the UK. Abroad, the Brits were paying nearly double that, at ~$8.50 per gallon.

Crude oil (the stuff that comes out of the ground) was more or less the same price wholesale in each country, as it’s traded on the global market. While the US is a leading producer of crude, it still imports much of its stock from other countries.

The discrepancy didn’t come from the price of the gasoline itself, but mostly from the taxes paid on the gas. In the US, gas taxes have always been shockingly low.

Singdhi Sokpo / The Hustle

The federal gas tax (an excise tax levied during the production process) was first charged in 1932 at 1 cent per gallon and is now 18.4 cents per gallon — an increase which tracks close to inflation.

But the federal gas tax hasn’t gone up since 1993. And as time has passed, the burden of the tax has weakened substantially.

Of course, states and many localities throw in additional taxes. Some states, like California and Illinois, issue taxes upwards of 60 cents. But according to August data from the US Energy Information Administration, the average state tax is 32 cents.

That puts the average American tax at ~50 cents per gallon — well behind most other large economies.

- The United Kingdom charges 52.9 pence per liter, or ~$2.45 a gallon, then adds another 20% tax to the total cost at the pump.

- The EU requires a tax of at least 0.36 euros per liter in member countries, or ~$1.41 per gallon. Most members charge more, with France at ~$2.67 per gallon and the Netherlands at ~$3.18 per gallon.

- Canada levies a national tax of ~38 Canadian cents per gallon or ~30 cents. Provinces can tack on their own taxes, which leads to Canadians spending ~90 cents to ~$1.50 a gallon on taxes.

When you take earnings into account, American gas is even cheaper, on a relative scale.

The cost for 100 gallons of gasoline, based on the average price in late July, takes up a smaller share of the country’s per capita GDP than any other nation in the world, including Iran, where people paid 20 cents a gallon last month.

Singdhi Sokpo / The Hustle

Iran subsidizes the cost of its state-owned oil, selling a vast supply to its own population at a discount.

It’s a strategy “to keep political peace,” according to Boston University economics professor Jay Zagorsky, and not entirely different from the US strategy of light taxation.

“Iran is actually taking a loss by selling that gasoline,” Zagorsky said. “The United States government is not taking a loss. They’re just taking a smaller cut than, as an economist, I believe they could be.”

Why the gas tax is low

On a recent afternoon, Angela Miller was trying to think of another way to get to work besides driving. The closest bus stop to her home in Conway, a suburb outside Little Rock, Arkansas, is 1.5 miles away.

“I’d have to walk that far just to get on a bus, assuming that one crosses the river [into Little Rock],” Miller said.

Similar issues exist in most rural, suburban, and urban areas in the US.

Contrast that with older European and Asian cities that continued to invest in transit during the highway era. Or with Canada, which despite following a similar growth trajectory as the US, has a more extensive transit system.

Singdhi Spokpo / The Hustle

In the US, without legitimate transportation alternatives, higher gasoline taxes would be punitive and hard to avoid.

But there’s also a chicken-and-egg situation at hand.

The US needs a low gas tax because there are very few alternative transportation options in sprawling metros — and the US has very few alternative transportation options in sprawling metros because it has a low gas tax.

“We became accustomed to cheap gasoline at the same time all this development was kicking off,” Golding said. “And they’ve been symbiotic institutions: cheap gasoline and more development and more space.”

Although it’s hard to tell whether cheap gas is primarily the result or the cause of Americans’ reliance on cars, it’s clear that many problems have arisen.

- The Highway Trust Fund, which finances the majority of federal spending on highway infrastructure and public transit with gasoline tax money, has foundered, requiring an infusion of $140B from general revenue sources since 2008 to stay afloat.

- Bad roads and ineffective public transit can lead to greater damage to cars and increased living costs. According to the Citizens Budget Commission, car-centric cities with cheaper housing, like Dallas and Houston, end up costing the same as New York City because of their pricier transportation costs.

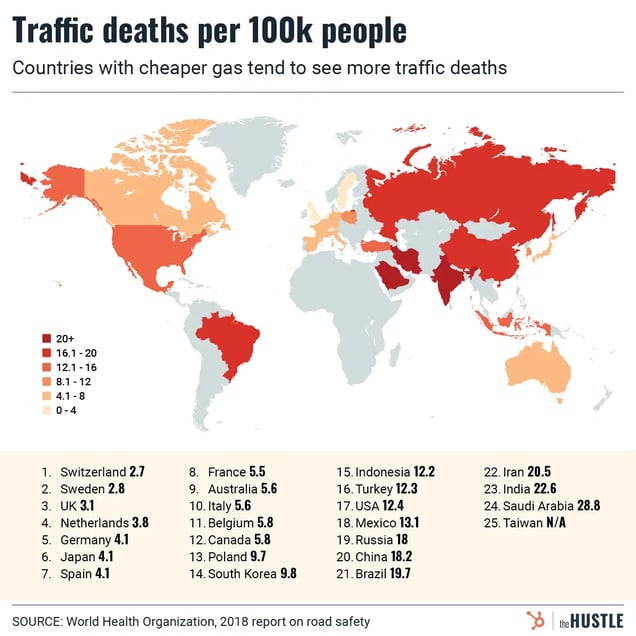

Some trade-offs from America’s low gasoline tax go beyond personal costs. Studies on raising the federal gasoline tax say the US could achieve societal benefits such as cleaner air, reduced congestion, and fewer traffic deaths.

Singdhi Sokpo / The Hustle

“Governments don’t pay for anything,” said Ted Kury, director of energy studies at the University of Florida. “The people pay, and if they’re not paying through taxes, then they’re paying through convenience, comfort, and safety.”

To cover the societal costs of driving, economists have thrown out several estimates for what America should charge as a federal tax, from ~$1 to ~$1.50 per gallon.

German economist Stefan Tscharaktschiew looked at Germany’s gasoline tax of ~$2.50 per gallon (one of the world’s highest) and found it should be ~48% higher to account for the burdens of driving.

Obviously, none of those suggestions have turned into reality. But most Americans are willing to pay more for their gasoline — if they believe they’ll get something in return.

The complications of raising the gas tax

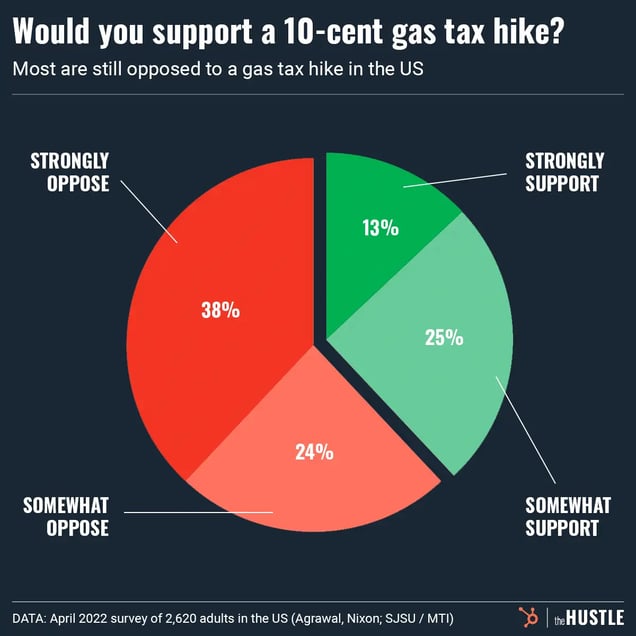

Every year since 2010, Asha Weinstein Agrawal, director of San Jose State University’s Mineta Transportation Institute’s National Transportation Finance Center, has asked Americans the same question: Would you support raising the federal gas tax by 10 cents to benefit transportation?

People have been surprisingly receptive to the idea.

Agrawal’s polls indicate the share of respondents who support a tax hike rose from 23% in 2010 to 48% in 2021, an increase she partially attributes to awareness of the country’s dilapidated infrastructure. In this year’s poll, taken mostly in February when inflation picked up, the share fell to 38%.

When the poll indicates the tax revenue would go to improving roads and reducing traffic and accidents, more than 70% of respondents have said they would favor raising the tax.

Yet raising the gasoline tax has been a dead end in politics.

- In 2006, then-Fed Chair Alan Greenspan argued for a raise in the federal tax as a “way to get consumption down,” to no avail.

- Independent presidential candidate Ross Perot had a plan to incrementally raise the tax by 50 cents.

- Last year, transportation secretary Pete Buttigieg said America may raise the gasoline tax. He walked back the suggestion a few days later.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Aside from the political pressure, there are many questions about equity and the efficacy of a gasoline tax hike:

- In 2020, the average American spent about ~2.5% of their total income on gasoline, a number that increased to nearly 4% this year.

- Lower-income Americans spend ~14% of their incomes on gas and typically live in areas that have the worst options for alternative transportation and fewer opportunities to work remotely.

Plus, there’s a distinctly 21st-century reason complicating the picture. Americans with higher disposable incomes could escape an increase in the gasoline tax by purchasing an electric vehicle.

“So if we do raise the gasoline tax, what we’re going to be doing is we’re going to make it more regressive,” said Zagorsky, the Boston University professor. “Because richer people are opting out of the system.”

Suggestions to counteract some of those negative effects have been bandied about for years, including:

- A mileage fee (which has solid support in Agrawal’s polls)

- A fluctuating gasoline tax that would rise and fall inversely to oil prices, steadying gasoline prices for people who plan budgets around fuel costs.

- A windfall tax on oil companies’ record profits (similar to the UK)

But nothing has stuck in the United States, and gas still feels expensive.

Learning that the US pays less than many other countries did little to remove the sting of this summer’s prices for Miller, the Conway, Arkansas, resident.

The last time she filled up, she was overcome by a strange mix of emotions. Gasoline was $3.59 a gallon, down from ~$4, and Miller was sad that she felt so excited.