The Great Resignation has been the economic buzzword of the pandemic.

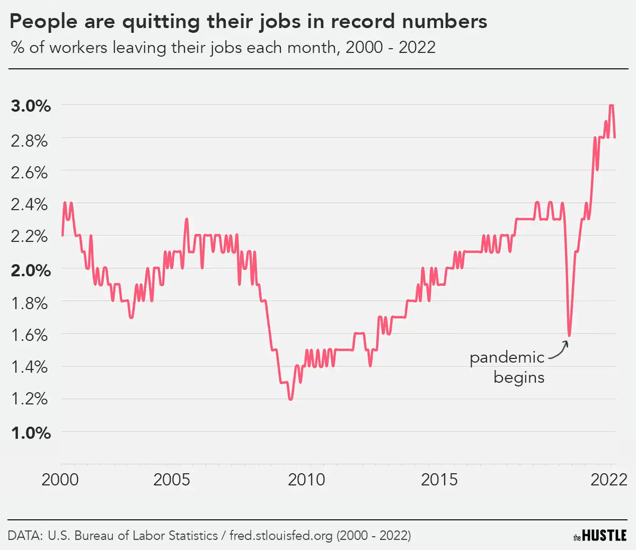

The share of workers voluntarily leaving their jobs escalated from a fairly typical 2.3% in January 2021 to new record highs of 2.8% last April, 2.9% in September, and 3.0% in December, per Federal Reserve data.

The “quits” rate hasn’t cooled much since, either. It was at 2.8% in January, the most recent month for data.

That’s 4.3m American workers leaving their jobs in one month.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Theories have abounded for why resignations have grown so prevalent.

The bump in these numbers has been attributed to burnout, a desire to switch careers, and the rise of the “antiwork” movement, which questions the status quo of modern employment. (The r/antiwork subreddit jumped from ~100k members at the start of the pandemic to ~1.8m as of March 2022.)

Some analysts have settled on the Great Renegotiation as a more accurate moniker for the situation because most people leaving their jobs have jumped to greener pastures at another employer.

But why are so many people really leaving their jobs? And what are they doing afterwards?

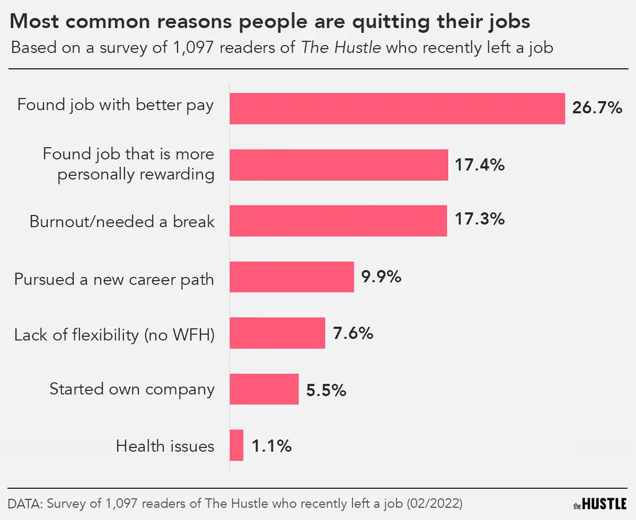

The Hustle surveyed ~1.1k people who left jobs during the pandemic and found a variety of reasons for why they resigned and where they ended up after their resignations.

Among the findings:

- ~27% of respondents left because they found a job with better pay. That reason was followed by finding a more rewarding job (~17%), burnout (~17%), pursuing a new career path (10%), lack of flexible work atmosphere (8%), and starting a business (6%).

- Burnout afflicted people of all professions. Respondents in the service-industry and blue-collar sectors were about as likely to say they were burned out as people in white-collar industries.

- 64% of respondents switched to a new job immediately, and 83% of them made more money at their new job.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

But the survey made it obvious the Great Resignation defies easy explanation.

Within these categories, the reasons for leaving a job were nuanced. One respondent’s burnout, for instance, was precipitated not just by strenuous work hours but also a subpar salary and diversity, equity, and inclusion issues from being one of the only women at her company.

To better understand these nuances, we decided to interview 4 people in varying industries, and at different stages of their careers, who left their jobs.

Here are their stories.

The restaurant worker who was tired of disrespect

Lucas Ochoa says people in the restaurant industry “are less and less willing every year to put up with” difficult work conditions and low pay. (Courtesy of Lucas Ochoa)

Lucas Ochoa arrived at work one day last November and realized he was in for a difficult shift.

Ochoa heard the entire kitchen staff at the downtown Louisville restaurant where he worked had walked out during lunch. For dinner, the staff would be down by about half. Ochoa would be the lone server’s assistant (also known as a busser or runner), down from the 3 server’s assistants he says the restaurant often had.

Ochoa, 24, had started about a month earlier as a job on top of EMT school. The work was tough. He carried heavy trays between the dining room and kitchen for 6-hour shifts, making minimum wage plus tips.

On good nights his hourly wage could come out to $20. But there were also bad nights, when he made far less doing the same difficult job.

And given the shortage of staff, this night was particularly crazy.

“I was running back and forth,” Ochoa said. “I’d already chugged like 3 Gatorades that evening.”

While he was carrying an order to a table, Ochoa says a general manager for the restaurant asked him if he could pick up another tray.

“I turned around and was like, ‘Hey, could you pay a living wage?’” Ochoa said.

The general manager, Ochoa said, told him he could leave and not come back. Ochoa agreed.

“I was like, ‘OK. I’m not gonna carry an entire dinner service on my back 5 nights a week, while being in EMT school and being disrespected.’”

Ochoa had been working off and on in the restaurant industry for 8 years and believed his anger at managerial treatment reached a boiling point during the pandemic. He was also emboldened knowing so many other jobs were available.

And it didn’t take him long to find his next one, at Starbucks.

At first, work as a barista suited Ochoa. The pace was easier, and he believed he was making decent enough money — $12/hour base pay and with tips closer to $15-$17 — while being treated with respect by management.

But not long ago, Ochoa said, he asked his manager whether Starbucks’ corporate pay raise would lead to higher pay for all employees at their store. He said the manager responded by cutting his work down to one shift per week.

With his hours reduced, Ochoa quit. He was again able to find another job quickly, in security. It pays more than Starbucks.

As necessary as he believes it was for him to leave his last 2 jobs, he’s still not in an ideal place.

“I’d honestly rather be making lattes,” Ochoa said over a text message. “But there’s no way I could make ends meet on one $12/hour shift a week.”

The working mother who wanted more family time

Verena Goetz, pictured with her daughter, Lina, realized during the pandemic she didn’t have enough time with her kids. (Courtesy of Verena Goetz)

Verena Goetz had a love-hate relationship with her work as an international move coordinator for a large moving company.

She enjoyed the work and the people, and she felt dedicated to the job. But the stress could be overbearing. Goetz wasn’t just coordinating the transportation of boxes; she was moving people’s most important possessions.

When the pandemic hit and shipping channels were thrown into disarray, her job became even more complicated. At the same time, Goetz started working from home, spending more quality time with her husband and daughter, and rethinking how she prioritized life.

Before the pandemic, Goetz noted, “you weren’t really just sitting down and spending time with your kids.”

In fall 2020, she had her 2nd child. As Goetz’s maternity leave winded down, she decided she didn’t want to return to work, at least temporarily.

But money was an issue. Her family resided in a Washington, DC-area condo and had plans to move to Seattle for her husband’s new job. Her ~$60k annual salary was necessary to pay for housing and living expenses.

Then, Goetz’s family got the break it needed when her husband discovered he could work remotely for his new job. In January 2021, Goetz resigned, and they moved to Antigua, Guatemala, where her husband is from and housing costs are roughly half what they paid in DC.

The time off from work has been rewarding, even necessary. Not long after arriving in Antigua, Goetz says she was diagnosed with stress-related ulcers.

Still, Goetz is “kind of itching to get back.” She’s done consulting work on the side and may pursue a new career in sustainability. But for now she’s enjoying seeing her children grow in a way she never expected.

“We just kind of try to make more time now,” Goetz said. “It’s changed our outlook a little bit.”

The new entrepreneur

Dominic Walton does not expect to return to the corporate world anytime soon. (Courtesy of Dominic Walton)

Corporate life was the only professional life Dominic Walton knew.

He had worked for a variety of companies, including Netflix and Charles Schwab and most recently Paychex. He liked his manager, but the long hours were getting to be too much.

“I noticed there is definitely more work than bodies, which you come to learn is just the nature of the corporate world,” Walton said.

“It became almost an expectation where people are smiling and giving you positive affirmations yet asking you to take on all these roles and additional work with no additional pay and not even keeping up with inflation.”

As his frustrations mounted, Walton thought back to a business idea he had before the pandemic. In June 2021, he created an LLC, and last September, at the peak of the Great Resignation, he officially quit and dove into Walton Logistics LLC full time.

Walton bought a 26-foot truck and transports general freight and goods, contracting with various companies that assign him long-distance trips or local work around his Phoenix-area home.

Walton says he was making ~$70k annually at his old job. With his own business, he says he can make $10k+ a month while working fewer hours and having the flexibility to spend more time with his young daughter.

“And I don’t mind getting sweaty and putting on some steel-toed boots and moving some pallets around and some tanks around,” he said. “I like the sweat and the hard work.”

Walton doesn’t expect a return to a traditional desk job, at least not in the near future. In the coming years, he would like to buy more trucks, hire drivers, and build his business.

The recent high school graduate who caught a break

Madeleine Pembelton plans to study biology in college before applying to veterinary schools. (Courtesy of Madeleine Pembelton)

To zero in on her goal of becoming a veterinarian, Madeleine Pembelton, 19, intended to take a gap year after graduating high school in 2021 to work as a veterinary assistant.

She finished ~200 hours of coursework on top of her high school AP classes for a veterinary assistant certification program and needed to complete 300 hours of clinic experience. The problem was that the pandemic reduced opportunities for in-person clinic work.

That meant no certification. And no certification meant much greater difficulty in securing a veterinary assistant job.

“The clinics I was interviewing with, I was declined because of lack of experience,” Pembelton said.

So Pembelton figured she would continue working at Pet Supplies Plus, a retailer in her hometown of College Station, Texas. At best, she assumed she might be able to pick up some hours as a kennel tech for a veterinarian, cleaning kennels and walking dogs.

Then, like almost everywhere else, veterinarians were hit by the Great Resignation. Pembelton interviewed at a local veterinarian office where several people had recently left.

“There was an opportunity there, and it was just perfect timing,” Pembelton said. “So I just jumped on it.”

She resigned from her job at Pet Supplies Plus (where she still visits former co-workers) and started working full time as a veterinary assistant. Pembelton makes higher wages and believes she’ll have an improved resume for when she starts college in the fall and applies to veterinary programs in the future.

Her good fortune probably wouldn’t have happened in any other job market.