In 1938, a New York cigar shop owner went to the bank to cash his daily profits.

As the teller sifted through the haul, she spotted an unusual $1 bill. It felt like cheap paper in her hands, the lettering was askew, and George Washington looked more like an animated corpse than a noble head of state. It was, no doubt, the worst counterfeit she’d seen in all her years.

The bill was sent to the United States Secret Service. Soon, thousands more just like it came pouring in, each more abysmal than the last.

For 10 years, agents searched far and wide for the source, launching the most extensive (and expensive) counterfeit investigation in American history. The culprit was deemed to be “the most successful counterfeiter of modern times” — a mastermind.

But the bills were made by no master: They were the work of a 73-year-old junk collector.

The beginning

Back in 1890, a 13-year-old boy named Emerich Juettner boarded a ship in Austria and set off through choppy seas for the promise of a better life.

He settled in New York City and soon found work as a picture frame gilder. But his true passion was the art of invention: Throughout his 20s, he spent late nights in a tenement apartment concocting various blueprints — everything from a new type of camera (rejected by Kodak) to specially engineered Venetian blinds (rejected by a window shade manufacturer).

Eventually, Juettner settled into life as a family man. By 1918, he was happily married with two children, and employed as a maintenance man at an Upper West Side apartment complex. For several decades, he enjoyed a modest and uneventful life.

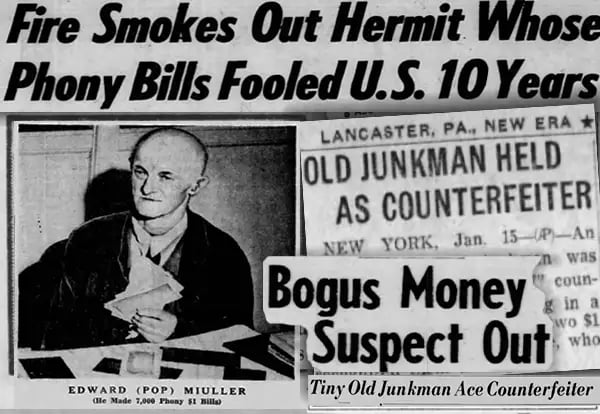

Juettner at the age of 73 (edited portrait via an original photo by Nick Peterson/NY Daily News via Getty Images, 1948)

But when his wife unexpectedly passed away in 1937, Juettner, then 61, found himself alone, “too old” to work in maintenance, and in financial peril.

His children had long moved out and started lives of their own, and the US was in the throes of a recession that saw a 30% decline in industrial production and sky-high unemployment rates. He was jobless with nowhere to turn.

So, the sexagenarian began collecting junk.

He bought a used, two-wheel pushcart and spent long days ambling about the streets of New York picking up the discarded goods of city dwellers and selling off the occasional find to a wholesale dealer.

But it soon became clear that this wasn’t going to cut it: He had to find a way to make money — fast — or he’d soon be out on the streets with the bric-a-brac.

The scheme

Juettner assessed his skills: In his youth, he’d acquired an “elementary knowledge” of metal engraving. During his time as an aspiring camera inventor, he’d also dabbled in photography. What could he make of that?

As it so happened, this was just the résumé for a career in counterfeiting.

At the time, replicating the look and feel of US currency was considered an expensive and difficult craft, reserved for criminal cartels with deep pockets. It was a technical process involving masterful artistry and specialized tools — and it was “nearly impossible” to elude authorities.

But Juettner would not be deterred.

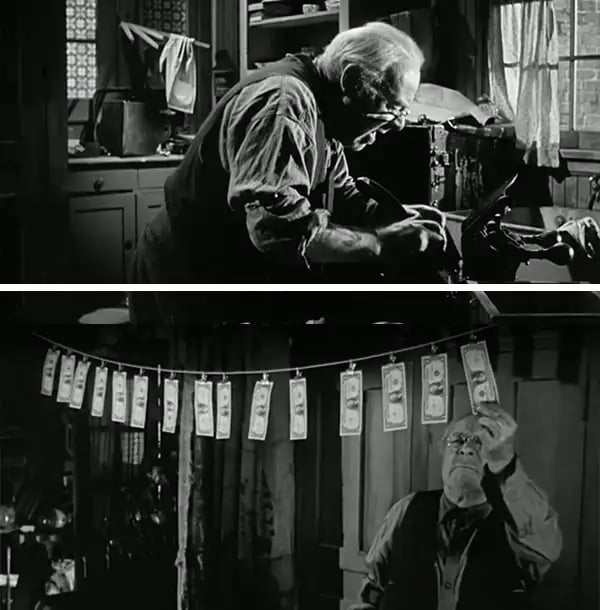

A dramatization of Juettner’s counterfeit operation, as seen in the 1950 film, Mister 880 (20th Century Fox)

One morning in November of 1938, he snapped pictures of a $1 bill, transferred the images to a pair of zinc plates (using, among other things, a bath of acid), then meticulously filled in small details of the bill by hand.

On a small hand-driven printing press in the kitchen of his brownstone flat at 204 W. 96th Street, he began minting fake $1 bills.

The search

The day after Juentter began his operation, the Secret Service, which handled counterfeiting cases at the time, received a curious $1 bill that had been passed off at a cigar shop on Broadway and 102nd Street.

It was like nothing they’d ever seen.

First off, no self-respecting counterfeiter had ever taken the time and trouble to replicate $1 bills (usually, it was higher denominations). Secondly, counterfeiters usually took great pride in their work: They were masters of their craft and vied to create currency so artistically sound that it was indistinguishable from the real deal.

But this bill was so poorly done that the Secret Service thought the perpetrator was intentionally mocking them.

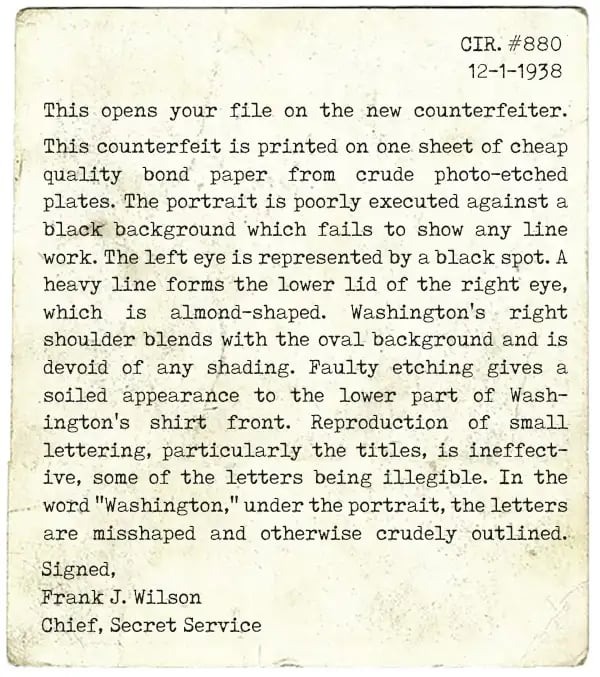

It was printed on cheap bond paper that could be found at any stationary store. The serial numbers were “fuzzy” and misaligned, the Secret Service later said. George Washington’s likeness was “clumsily retouched, murky and deathlike,” with black blotches for eyes.

And just for good measure, the ex-president’s name was misspelled “Wahsington.”

Within the month, 40 more of the very same $1 bills, used to buy goods at shops all over the city, showed up at the crime lab. By mid-1938, the tally grew to 585.

The Secret Service dubbed the mystery man “Mister 880,” after his case file number.

For James J. Maloney, the supervising agent of the Secret Service’s New York bureau, the hunt was an “unbearably provoking” experience.

Under his tutelage, the Secret Service had seized millions in counterfeit bills, oftentimes before they even went into circulation. The demise of most of these counterfeiters was greed — but Mister 880 was different.

He seemed to use his bills just enough to survive, never passing off more than $15 per week. He also never spent money in the same place twice: His “hits” spanned subway stations, dime stores, and tavern owners all over Manhattan.

Investigators set up a map of New York in their office, marking each $1 counterfeit location with a red thumbtack. They handed out some 200,000 warning placards at 10,000 stores. They tracked down dozens of folks who’d spent the bills.

But 10 years came and went, and the search for Mister 880 turned into the largest and most expensive counterfeit investigation in Secret Service history.

By 1947, the Secret Service had documented some $7,000 of the distinctively terrible fake $1 bills — about 5% of the $137,318 of fake currency estimated to be in circulation nation-wide.

As it turned out, the worst counterfeiter in history was also the most elusive. And it would take a fire (and a crew of 12-year-old kids) to smoke him out.

The tip

On a chilly afternoon in January of 1948, 7 schoolboys were rustling around in a vacant lot in the Upper West Side and uncovered something strange.

Buried in the snow, among a pile of car tires, old bird cages, and a rusty baby carriage, were two zinc engraving plates and “30 funny-looking dollar bills.” While shopkeepers all over the city had accepted the bills without hesitation, the gaggle of 12-year-olds immediately identified them as fakes.

A week later, one boy’s father caught him playing poker with a strange bill and turned it into the police, who handed it over to the Secret Service.

After some investigative work, they determined the plates were in the hands of one John Canning, an industrious 10-year-old who’d acquired them through the trade of a Japonese bayonet. The plates, they determined, were the work of their mystery man, Mister 880.

They soon tracked down the lot where the boys found the plates and learned that a few weeks earlier, there had been a fire in a bordering apartment; the firefighters had entered to find the place full to the brim with junk, and had thrown them out the window into the alley to make room.

The Secret Service had their guy. “Mister 880” was about to get a name.

The capture

Agents busted into the brownstone, expecting to find a criminal mastermind.

Instead, they were greeted by a jovial 73-year-old — “5’3” tall, [with a] lean hard muscled frame, a healthy pink face, bright blue eyes, a shiny bald dome, a fringe of snowy hair over his ears, a wispy white mustache, and hardly any teeth.”

It was Emerich Jeuttner, the old junk collector.

Juettner seemed unfazed and endearingly aloof. When answering questions, he’d pause and offer a toothless grin. Nonchalantly, he admitted to his crimes:

“How long have you been making these bills?”

“Oh, 9 or 10 years — a long time.”

“You admit it?”

“Of course I admit it. They were only $1 bills. I never gave more than

one of them to any one person, so nobody ever lost more than $1.”

All this time, their man wasn’t trying to hide at all.

In an examination of the apartment, agents found a printing press, ink, photo negatives, and a drawer full of $1 bills that didn’t meet his bar of quality.

Shortly thereafter, Juettner — also known by the aliases “Edward Mueller” and “Edward Miuller” — was arrested and escorted downtown.

On September 3, 1948, Juettner’s case came before judge John W. Clancy in US District Court in New York City. He faced 3 counts, all bearing possible 10-year sentences: Possession of counterfeit plates, the passage of counterfeit bills, and the manufacturing of said bills.

Adorned in a frayed gray suit and a wrinkled felt hat, Juettner sat quietly in the hot seat, flashing the occasional grin to the court stenographer.

The man’s age (73) and likeability did a number on the judge: Juettner was given a dramatically reduced prison sentence of 1 year and 1 day — a duration that allowed for parole after 4 months.

And, for good measure, he was made to pay a fine of $1.

The payoff

Shortly after the trial, St. Clair McKelway, a New Yorker reporter, covered Juettner’s saga in a 3-part series (1, 2, 3). This drew international attention to the case and led to an Academy Award-winning film (“Mister 880”) in 1950.

Through the optioning of his life rights, Juettner ended up making more money from the film than he had in his 10 years as a counterfeiter.

He returned to a life of normalcy, and lived out the rest of his days in the suburbs of Long Island, where he died in 1955, at the age of 79.

Years before his death, a reporter at the New York Daily News asked Juettner if he’d ever considered returning to a life of counterfeiting, the craft to which he’d so unskillfully devoted more than a decade.

“No,” he responded. “There wasn’t enough money in it.”