On April 25, 2014, a bulldozer ripped into a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico, and unearthed a trove of 30-year-old Atari video games.

As a dust storm swept across the desert plains, a small gathering of intrepid nerds huddled by a chain-link fence to survey the find. They were there to get a glimpse of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial — a game so bad that it was blamed for toppling the $3.2B video game industry in 1983.

For the game’s creator, Howard Scott Warshaw, it was an excavation of his past.

Once the most highly coveted game developer — a hit-maker with the Midas touch — he had been immortalized as the man who created E.T., the “worst” video game in history.

But Warshaw’s story, like that of Atari, is a parable about corporate greed and the dangers of prioritizing quantity over quality.

Not a computer guy

Growing up, Warshaw was the kind of kid who wrote his own sets of rules for board games like Monopoly and Risk.

As a teenager in the early 1970s, he witnessed the birth of the commercial video game industry — including the rise of wildly popular arcade games like Atari’s Pong (1972) and the release of the first home console, the Magnavox Odyssey.

When he was introduced to computers as an economics student at Tulane University, he fell in love — mostly because the coursework didn’t require him to read books or write long papers. He went on to earn a master’s degree in engineering, then settled into the workforce as a multi-terminal programmer at Hewlett-Packard.

But Warshaw soon found himself wanting more.

A self-proclaimed “wild guy,” he wasn’t crazy about the tame lifestyle at HP. At the suggestion of a friend, he decided to apply to Atari.

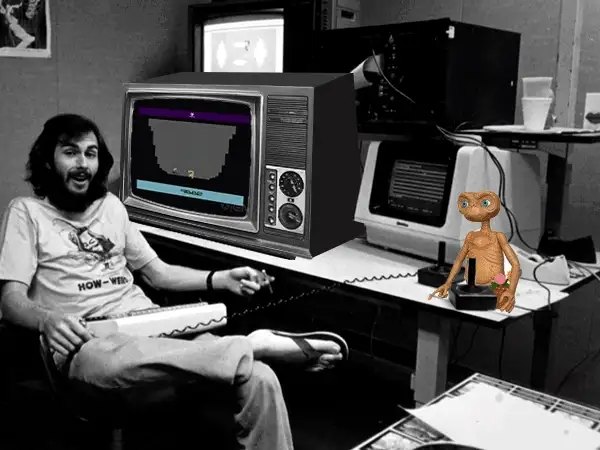

Warshaw at the Atari headquarters in the early 1980s (courtesy of HSW)

Founded in 1972 by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, Atari had grown from an arcade game maker into what was then the fastest-growing company in US history — a $2B-per-year ($6.2B in 2019 dollars) behemoth with 80% market share.

Warner Communications, which had purchased Atari in 1976, was thirsty for more.

At the time, video games were in the midst of a golden age. Driven by hits like Space Invaders (1978), Asteroids (1979), and Pac-Man (1980), the coin-op arcade industry was, by the early ‘80s, more profitable than Hollywood and the pop music industry combined.

The holy grail was in replicating these arcade games in a play-at-home console. Atari, which had recently released its VCS (later renamed the Atari 2600), was well-poised to dominate its competition.

To attract the best programming talent, Atari cultivated a work culture that included hot tub meetings, frequent keggers, and lots of weed. For Warshaw, it was the promised land — the perfect combination of adventure and innovation.

On January 11, 1981, he left HP, took a 20% pay cut, and joined Atari as a $24k-per-year programmer.

The hit-maker

Despite having no game development experience, Warshaw, 24, was tasked with building new play-at-home games on microchips using real-time computer programming.

“I thought, ‘What am I going to do to truly make a contribution here?’” he told The Hustle in a recent interview. “I wanted my games to be the biggest games anyone had ever seen.”

Soon, Warshaw’s wish would come true.

An ad for the Atari Video Computer System, later renamed the Atari 2600 (via AtariAge)

His first game, Yars’ Revenge — a story about mutated houseflies under siege — took him 7 months to develop, and went through another 5 months of rigorous play-testing. When it hit the shelves in May of 1982, it became Atari’s biggest 2600 game of all time, selling more than 1m copies.

The success of this game netted Warshaw a high-profile follow-up assignment: the video game adaptation of the Steven Speilberg film, Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Released in November of 1982 after 10 months of development, this, too, was a 1m-copy seller.

Warshaw soon became known as the game designer with the golden touch — and his success earned him rockstar status. According to press reports, he purportedly pulled in $1m a year and was “hounded for autographs by a devoted cult following of teenagers.”

But in mid-1982, Atari had also begun to shift its business strategy in the games department.

In its earlier days, Atari gave programmers ample time (5-10 months) to create and develop innovative games. But that window closed when the company realized that the real road to riches was in licensing the rights to films.

When Raiders of the Lost Ark saw success, Atari’s culture shifted from one led by engineers to one dominated by sales and marketing employees tasked with rushing games to the market.

Warshaw’s first game, Yars’ Revenge, was a smash hit, selling over 1m copies in 1982 (via eBay)

“The theory was that if you got a super hot license, you could put anything out there and it would make a lot of money,” said Warshaw. “Licenses were a whole new world at the time… Atari didn’t believe you could have a negative backlash over a video game. They had an attitude that you could do no wrong.”

But that new philosophy would challenge Warshaw’s hot streak.

The making of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

Speilberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial premiered at theaters in June 1982. It was a smash hit, grossing $322m in one year — at the time, the highest figure the film industry had ever seen.

Behind the scenes, a month-long bidding war erupted to license to the video game. When the dust settled, Warner shelled out a purported $20-25m ($52–65m in today’s dollars) for the rights.

On July 27, Warshaw got a call from Atari’s then-CEO, Ray Kassar.

“Kassar called me on a Tuesday afternoon,” recalls Warshaw. “He said ‘On Thursday morning at 8 am, there will be a Learjet waiting for you at San Jose International Airport; you’re going to come to Burbank and present your design to Steven Speilberg.’”

Atari wanted to roll out the game for Christmas, which meant it would have to be done by September 1st.

Warshaw (right) with Steven Spielberg (Photo: Dave Staugus)

The typical game took 1k hours’ worth of work over 6 months. Warshaw had less than 36 hours to come up with a concept to present to Hollywood’s hottest director.

Worse yet, he had just 5 weeks to finish the game — a task that one reporter called “the computer equivalent of simultaneously composing and playing a minute waltz in under 30 seconds.”

“The reason a game takes 6 months is there’s a lot of tuning and tweaking; you work on the game until you have a good one and the variable is time,” said Warshaw. “In this case, it was an inversion of that: Instead of starting with the goal of making a good game, it’s, ‘OK I have 5 weeks — let’s see how good of a game I can make.’”

Warshaw’s only option was to create a small, simple, replayable game — something with few moving parts that he could implement quickly.

Less than 2 days later, he was standing in a conference room in Burbank, pitching his design to Spielberg: The player would guide E.T. through a landscape filled with pits, and collect pieces of a phone while evading FBI agents.

“He just looked at me and said, ‘Can’t you just do something like Pac-Man?’” recalls Warshaw. “But eventually, he approved it.”

Left: An ad for Atarti’s E.T. (via Wikipedia). Right: screenshots from the game (via YouTube)

Over the next 35 days, Warshaw holed himself up in his house working 14-hour days. Over 5 weeks, he estimates he put 500 hours of work into the game, doing everything he could to make something halfway decent in the time he was given.

In December of 1983, some 5m E.T. cartridges hit shelves across America. Atari had high hopes that it would be one of the best-selling games of all-time.

But fate had something else in store.

In the pits

Initially, the E.T. video game sold well.

An extra-terrestrial craze had gripped the nation, and parents, desperate to buy their kids anything E.T.-related, bought thousands of copies, wrapped them, and put them under the tree. But in early 1983, when kids actually started playing the game, things quickly turned sour.

It became clear that E.T. had committed what Warshaw calls “one of the fundamental sins” of video game design: It disoriented the player.

The specific complaint centered around the pits, which players couldn’t seem to avoid falling into: “If you take a step in any direction, you fall into a hole,” said one reviewer. “And if you get out of the hole, you fall right back down.”

“A video game needs some level of frustration, or else there is no satisfaction in the win,” said Warshaw. “But there’s a difference between frustration (‘I know what I’m trying to do, I’m just falling short’) and disorientation (‘I’m suddenly in a world I don’t understand, and I don’t know how I got there’).”

Initially priced at $38, the game was soon on sale for $7.99. Millions of copies went unsold, and thousands more were returned.

Ads from 1982 and 1983 show the decline in the price of the E.T. video game (assorted clippings, via newspapers.com)

Unfortunately for Warshaw, the flop of E.T. coincided with a much graver event: The video game crash of 1983.

A flood of low-quality, hastily created games, coupled with the rise of the personal computer, led to a moment of reckoning: In the 2 years following the release of E.T., the video game industry saw its revenue fall from $3.2B to just $100m — a 97% decline.

By the end of 1983, Atari reported $536m in losses. Over a 12-month period, the company went from 10k to 2k employees, and its stock slid from $60 to $20. In mid-1984, Warner sold the ailing company for $50 cash and $240m in stock.

In the wake of this crisis, E.T. became a symbol of everything that was wrong with gaming. Analysts blamed it for sending the gaming industry into a “decades-long death spiral.”

But true insiders knew that E.T. was merely a symptom — not the cause — of the crash.

“It wasn’t E.T.,” Nolan Bushnell, a co-founder of Atari, later said of the crash in a 2014 documentary. “It was a combined effect of a lot of missteps in technology, deployment, marketing… [but] a simple answer that is precise will always have more power than a complex one that is true.”

“Any time a tragedy happens,” said Warshaw, “you need a face to tell a story.”

E.T.: The great unearthing

At some point during Atari’s fall in 1983, the company loaded up 20 truckloads of games — including thousands of unsold copies of E.T. — and dumped them in a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico. History, the company hoped, would be forgotten.

Over the years, the burial became something of an urban legend. But 31 years later, in April of 2014, a crew excavated the site and uncovered 1.3k games. At auction, the E.T. cartridges, which have since developed a cult following, fetched as much as $1.5k.

For Warshaw, it was a vindication of sorts.

Warshaw, with all 3 of his Atari games (courtesy of HSW)

After Atari crumbled, his outsized role in the video game crisis earned him a scarlet letter in the industry. He found work as a real estate broker and spent nearly 2 decades soul searching before discovering his true passion: psychotherapy.

Today, he spends his time working on “a much more sophisticated piece of hardware:” the human brain — particularly those of Silicon Valley techies.

But on that day in 2014, when E.T. was resurrected from the dead amid a crowd of cheering fans, Warshaw felt a strange sense of pride.

“Now, I kind of prefer it when people call E.T. the worst game ever,” he says. “Yars’ Revenge is considered one of the best games, so as long as E.T. is the worst, I have the greatest range of any designer in history.”