He called himself the “Black Thomas Edison,” but we should all know his true name: Garrett Augustus Morgan.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Morgan pioneered a wide range of technological advancements — predecessors to the gas mask, sewing-machine advancements, hair products, and the first 3-color traffic light — that continue to impact daily life decades later.

It’s the story of an insatiably curious soul who overcame tremendous social barriers and devoted his life to making the world a safer place.

And it began in a shack on a rural Kentucky farm.

The son of freed slaves

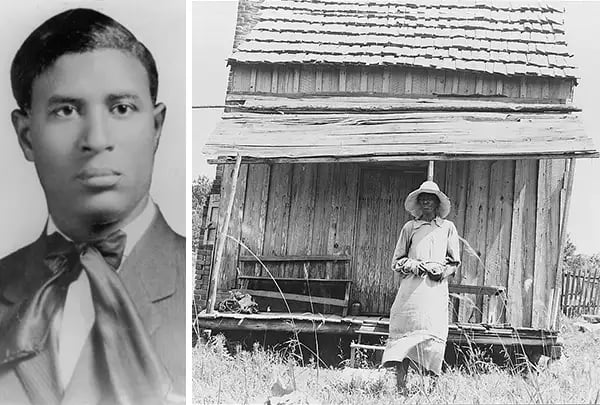

Born to former Southern slaves in 1877, Morgan began life with bleak prospects and limited freedom.

His parents had gained freedom a decade earlier. But like many ex-slaves, they’d been forced into a life of sharecropping during the Reconstruction Era. In exchange for labor, they were permitted to rent out a rustic cabin on a white landowner’s farm in Claysville, Kentucky.

Left: Morgan as a young man (Western Reserve Historical Society); Right: A typical sharecropper’s cabin (Dorothea Lange; 1937)

Morgan and his 10 siblings were put to work around the age of 5, tilling fields, weeding, and caring for the farm’s pigs and chickens.

He attended a one-room, all-Black elementary school, where he learned basic reading, writing, and math. But after graduating from the 6th grade, his educational options ran dry. He had 2 choices:

- He could return to the farm as a sharecropper

- He could venture out and try his luck elsewhere

In 1891, at the age of 14, Morgan migrated north to Cincinnati.

America was in a state of immense industrialization. Factories and mass production were replacing the agrarian way of life, railroads were rapidly expanding, and a mass migration to cities was ushering in a new era of invention.

For 4 years, Morgan worked as a handyman for a landlord, using his earnings to hire a tutor and enrich his education.

At 18, with just 10 cents to his name, he moved to Cleveland, the city where he’d find success.

A natural inventor

In Cleveland, Morgan found work as a custodian, sweeping floors for $5/week (~$130 today).

But according to the author Mary Oluonye, Morgan was an insatiable problem solver who soon craved more hands-on experience.

Cleveland, c. 1900 (Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

At the time, Cleveland was one of the nation’s leading clothing production hubs. Morgan managed to land a job fixing sewing machines — a crucially important role in the city’s bustling Garment District.

He studied the machines closely, took note of their flaws, and — with extraordinarily finite resources — fashioned his own belt fastener that improved workflow. He sold his first invention for $150 ($4.6k today) and gained backroom renown for his ingenuity.

After 12 years in the clothing business, Morgan decided to strike out on his own.

Along with his newly-wed wife — a Czech immigrant seamstress — he launched his own sewing-machine repair firm and a clothing manufacturing shop that he grew to 32 employees.

While looking for a way to prevent needles from scorching fabrics, Morgan formulated a chemical concoction with an unintended side effect.

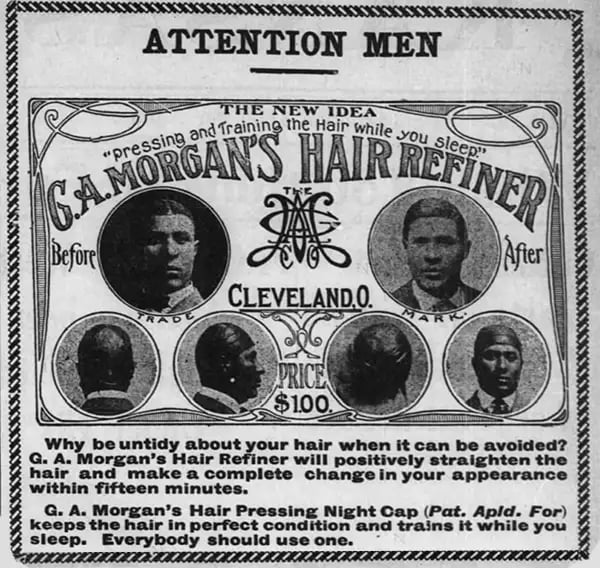

When the solution was applied to cloth, it straightened out curly fibers. After running a series of tests on his neighbor’s Airedale terrier, then on his own hair, Morgan incorporated G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Co. and began to market hair products to the masses.

He traveled around the country selling his hair refiner for $1/jar ($27 today), netting $20k in sales within a few years.

An ad for Morgan’s hair products (Kansas City Advocate; 1916)

At a time of deeply ingrained racial prejudice, Morgan enjoyed rare financial success: He bought a home and, according to the historian William King, was the first Black person in Cleveland to own a car.

But Morgan’s entrepreneurial streak had only just begun.

Saving lives and making a name

Morgan shifted his focus to a dramatically different field: fire safety.

He noticed that the existing devices firefighters used to protect themselves from smoke and noxious fumes were clunky, unreliable, and prone to malfunctions.

So, he decided to design something better.

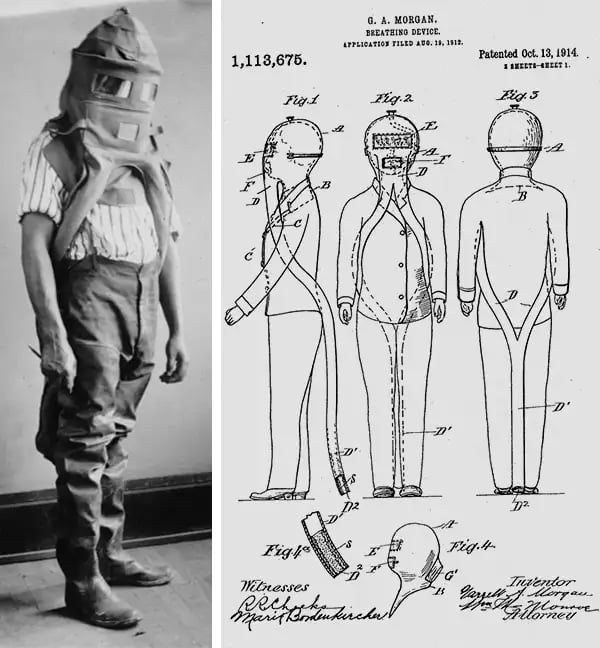

In 1912, Morgan filed a patent for a fire safety hood (the Garrett A. Morgan Safety Hood) that utilized a series of tubes, which ran down to the floor where clean air could be collected through a wet sponge filter.

Morgan sought advice from J.P. Morgan (then one of America’s richest men, with a net worth equivalent to ~$47B today) and the financier advised him to “remove himself from his own product” — presumably, to downplay his race.

To market his device, the Black inventor hired white actors for a series of live demonstrations. Donning the hood, a man would enter a tent filled with smoke “thick enough to strangle an elephant,” and emerge 20 minutes later with no side effects.

Sold for $25 each ($665 today), Morgan’s fire hoods received rave reviews from those who put them to use: “Two men equipped with the Morgan helmet can accomplish more in 15 minutes than a whole company can in 30,” wrote one Ohio fire chief in 1914.

Left: A Morgan Safety Hood on display (Western Reserve Historical Society); Right: Patent illustrations for Morgan’s invention

On July 25, 1916, the invention gained national prominence.

In the wake of a natural gas explosion in a tunnel under Lake Erie, Morgan and a crew of white volunteers used the masks to rescue crew members and exhume bodies.

While the white volunteers were awarded medals and cash prizes for heroism, Morgan’s contributions went largely unrecognized in the mainstream press.

But after the event, demand for his safety hoods multiplied.

Fire departments in more than 500 cities bought the invention — and Morgan soon secured contracts with the US Navy and US Army.

During WWI, an iteration of his hood was used extensively on the battlefield to protect against German gas warfare.

He incorporated the device under his own publicly-traded firm, The National Safety Device Company, and sold shares for $10. Within 5 years, these shares were up to $250 — a 25x return for investors.

Putting the ‘yellow’ in traffic lights

Morgan was endlessly curious about the minutiae of daily life — the somewhat dull things around him that few others gave thought to.

And in 1922, he turned his attention to the traffic light.

America’s cities were undergoing dramatic urban shifts to better accommodate the booming automobile industry. The streets were packed with cars, carriages, horses, bicycles, and pedestrians — and new traffic regulation was needed.

Traffic lights that utilized red (stop) and green (go) were widely in use at the time. But, Morgan saw room for improvement.

After witnessing a terrible accident between a car and horse-drawn carriage, he devised a T-shaped light that integrated the first “middle” position — the color yellow — to denote the light was about to change.

Top: Patent illustrations for Morgan’s traffic light (WIPO/USPTO); Bottom: Moran in his later years (Western Reserve Historical Society; photo illustration: The Hustle)

He demonstrated the light in Willoughby, Ohio, where it caught the attention of local General Electric employees.

In 1923, the company paid Morgan $40k ($620k today) for his patent and began to install his lights all over the country, ushering in the age of the 3-color traffic lights we know today.

A life to remember

As he aged, Morgan continued to not only innovate but also fight for a more inclusive society.

He launched a newspaper that covered oft-unpublicized events in the Black community, became actively involved with the NAACP, and established an all-Black country club on a 121-acre farm outside of Cleveland.

Despite developing glaucoma and slowly losing his eyesight, he patented a number of other devices, including a pellet that extinguished cigarettes when people accidentally fell asleep smoking.

When he passed away in 1963, at the age of 86, he was laid to rest in the same cemetery as ex-President James Garfield and John D. Rockefeller.

“He has a wonderful inventive brain with remarkable business ability,” the Kansas City Advocate wrote of Morgan.

“He has accomplished so much without the learning of books — but rather, as he puts it himself, [through] the college of hard knocks.”