Bitcoin has had a banner start to the year.

Less than 2 months after breaking the $20k barrier for the first time, the digital currency more than doubled in price, hitting a high of $49,344 this week.

Every time bitcoin is proclaimed to be dead, it seems to surge back, buoyed by bullish investors, favorable legislation, and tech titans’ tweets.

At this point, nearly everyone has heard of bitcoin. But many folks still don’t quite understand how the currency is created.

It’s not printed like cash. It’s not a physical object like a gold bar. It’s not stored on a piece of plastic like a debit card. It just exists somewhere in a vast digital expanse until it’s excavated into circulation by a so-called bitcoin miner.

In this illustrated guide, we’ll cover the following:

- How bitcoin is created (a process called mining)

- How the economics of mining have changed over time

- The effects this process has on power consumption

The digital miner

To help explain all of this, we’d like to introduce you to a man named Willy “Wild Eyes” Tibbs.

Wild Eyes made a fortune in the California Gold Rush in 1849. Now — 170 years later — he’s back from the grave for his next prospecting adventure.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Wild Eyes has heard that there are riches to be made in mining a newfangled digital resource called bitcoin.

As he sees it, bitcoin shares a few similarities with gold:

- There’s a finite supply: As dictated by bitcoin’s creator, there can only ever be 21m total coins.

- They must be mined: The only way to release new bitcoin into circulation is through the efforts of digital excavators.

Wild Eyes digs a little deeper and finds out that bitcoin was created in the wake of the financial crisis in 2008 by an elusive pioneer (or group of pioneers) under the alias of Satoshi Nakamoto.

Nakamoto’s mission was to create a decentralized currency system that wasn’t beholden to middlemen. Among it’s touted benefits:

- It’s democratic: Unlike paper money, where a single central authority like a bank manages a record of all transactions, bitcoin is minted, circulated, and audited by thousands of users.

- It’s harder to manipulate: Government agencies can’t intercede by doing things like increasing volume or fiddling with interest rates.

- It’s global: Someone in Tennessee can instantaneously trade bitcoin with someone across the globe in Tokyo at a low cost.

The backbone of this concept is a distributed network called the blockchain, where a record of all bitcoin transactions is stored.

Now, for an old-school argonaut like Wild Eyes, this is a tad complicated.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

To help him out, let’s step back a bit and briefly explain the blockchain using something he can understand: a choo-choo train.

Imagine that the blockchain is a loooong train — a blocktrain, if you will.

This train contains a public record of all bitcoin transactions. Each time a trade is made through a cryptocurrency platform like Coinbase, the details of the transaction are coded and broadcast, along with other transactions, to a vast network of users called bitcoin miners.

From there, the following process unfolds:

- Miners compete to add the next car to the train by bundling up a bunch of transactions into “blocks.”

- Miners solve a computational problem (called “proof of work”) that assigns the block an identifying code (a hash).

- The “winning” block is distributed to, and verified by, all the other miners in the network and is added to the blockchain.

Only one car can be added to the train at any given time, and each one takes ~10 minutes on average to verify and attach.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

These bitcoin miners serve 2 major functions:

- They are the printing press of bitcoin: Adding new blocks to the blockchain is the only way to release new bitcoin into circulation.

- They are the auditors of bitcoin: Through the process of mining, they verify the legitimacy of all transactions on the blockchain.

By solving the equation first and adding the next block to the chain, a miner is rewarded with a set amount of bitcoin.

When bitcoin mining first started, the reward was 50 bitcoin (BTC). But as dictated by the coin’s creator, the reward is cut in half every time 210k new blocks are added to the chain — or roughly every 4 years.

As of February 2021, miners receive 6.25 bitcoin for every new block they mine — or ~$294k based on the current market value. They also get to keep the transaction fees from the trades in that block, which are currently around $20/trade.

Today, it’s estimated that there are more than 1m bitcoin miners in operation — and they’re all competing to add the next block to the chain.

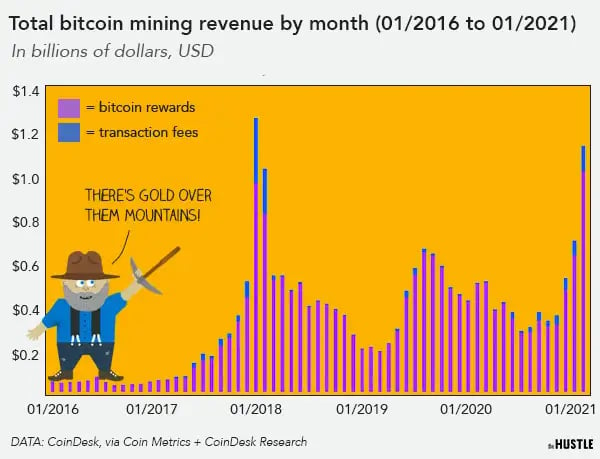

Combined, the rewards these miners earn top $1B per month.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

On paper, these numbers make mining an extremely appealing pursuit for folks like Wild Eyes.

But as it turns out, the money’s not so easy to come by.

The bitcoin mining arms race

As mentioned above, a bitcoin miner has to solve a computational problem in order to successfully add a new block to the blockchain and receive his reward.

We won’t get into the nitty-gritty of that problem here (check out this post for a full breakdown on the math).

But in simple terms, a miner basically has to employ a computer to run through trillions of hexadecimal number combinations until it spits out an acceptable 64-character code. This coding keeps the blockchain secure.

The difficulty of this problem adjusts in proportion to the network’s total mining power: As more bitcoin miners join the network to compete, the problem becomes harder to solve, thus requiring even more computing power.

This led to something of a bitcoin mining arms race.

A decade ago, it was possible to mine bitcoin using a simple computer processor. But as mining began to spread, people utilized more powerful hardware like GPUs (graphics processing units), FPGAs (field-programmable gate arrays), and dedicated ASIC mining machines.

The volume of miners on the network — and the random nature of number generation — has made winning a block reward into a lottery.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Bitcoin miners have to weigh the cost of hardware (and more importantly, the cost of the electricity required to run it) against the slim odds of winning on a regular basis.

In most cases, operating alone is no longer financially viable.

Let’s say Wild Eyes bought an old ASIC machine — say an Antminer s9 (~$400 on eBay) — and rigged it up in his basement. According to bitcoin mining calculators, it would likely take him 225 years to generate a block.

And while sitting around waiting for that to happen, he’d spend ~$3.50 per day (~$1.3k per year) on electricity just for the one machine.

For this reason, today’s bitcoin mining scene is dominated by 2 factions:

- Mining pools: Groups of individual miners who combine their computing power, then divide any rewards up proportionally, based on how much computing power each person contributed

- Massive mining “farms” that have thousands of machines running 24/7

Around 66% of the world’s bitcoin mining now happens in China, where cheap hardware makes large operations more economically feasible.

In Dalian — China’s bitcoin mining capital — one factory alone mines 750 bitcoin per month, or $35.6m in value at the current market rate. To do so, it utilizes 3k+ ASIC machines and spends $1m+ per month on electricity.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Averaging across all types of operations, one bitcoin costs between $5k and $8.5k to mine. Power makes up the vast majority of the overhead.

The key for many mine operators is to plunk down where electricity costs are especially cheap — places like Iceland, upstate New York, small towns in Washington State, and rural Texas.

But power consumption isn’t just an economic consideration, it’s one of the biggest controversies in the practice of bitcoin mining.

The power problem

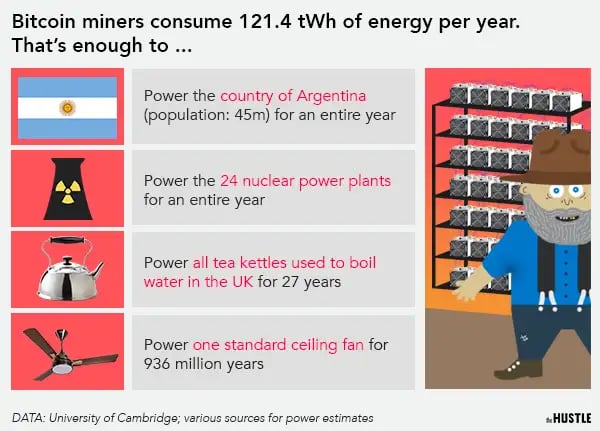

Collectively, bitcoin miners use 121.4 terawatt-hours (tWh) of electricity per year to sustain their operations.

To give that number some additional context, that’s enough to power the entire population of Argentina (45m) for an entire year.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Of course, traditional financial institutions aren’t much better.

It has been estimated that the world’s banks collectively consume at least 100 tWh of power per year, when factoring in branches, servers, ATM machines, and paperwork.

Eventually, though, the power used by miners will be a moot point.

Roughly 18.6m (88.5%) of the possible 21m bitcoin have already been mined. At the current rate, the final bitcoin is projected to be mined in the year 2140.

Most of the gold, so to speak, has been snatched from the streams. So ol’ Wild Eyes may be better off just buying bitcoin on the open market.