It took about 5 minutes for an algorithm to putter through the vast complexities of my DNA and spit out 16 “personalized” strains of weed.

I’d relinquished my raw genetic data — some 560k+ single-nucleotide polymorphisms huddled together in a .txt file — to a platform called Strain Genie, which promised to “use [my] DNA to help [me] find the right cannabis products.”

The result, a 19-page “Cannabis Health Report,” informed me that I was at risk for Alzheimer’s and suggested I smoke some Purple Bubba to fortify my memory.

Strain Genie is one of a growing crop of companies seeking to “democratize” DNA data. Our genetic information, they pitch, can tell us everything from the roommates we should choose, to the wines we should be drinking.

But how useful are these claims? As science currently stands, can DNA reliably shed light on our individual tastes and preferences as consumers?

The ‘Netflix of weed’

In 2017, Nicco Reggente took a 23andMe DNA test and found out he had a long-lost half-brother.

Reggente, a budding entrepreneur (and then-Ph.D. candidate at UCLA), had a revelation: “I thought, maybe I could leverage DNA to gather information about my customers and help them make better purchasing decisions.”

See, a few years earlier Reggente and some fellow Ph.Ds had launched the “Netflix of weed” — a platform called WoahStork that collects data on thousands of marijuana strains, asks users to fill out a medical questionnaire, then enlists an algorithm to “intelligently” recommend the right products for the right people.

Our DNA, he reasoned, makes us who we are. So why should its applications be limited to ancestry and medicine? Couldn’t it also help us make sense of, say, kush?

What came next was Strain Genie, the world’s first “personal cannabis DNA test.”

Weed, it turns out, is an extremely complicated lover: There are more than 10k strains on the market, each with a different composition of cannabinoids (like TCH and CBD) and terpenes (organic compounds). When we consume cannabis, these compounds interact with our endocannabinoid system, a complex network of receptors that impact things like our appetite, mood, memory, and pain sensation.

The proven science of weed and its effects on us is still pretty hazy — and most experts say the link between DNA and weed is largely undefined.

But Nicco Reggente is not the type of guy to wait for the slow march of traditional science.

Taking things into our own hands

Today’s direct-to-consumer DNA market rests on an underlying tenet of transhumanism: The belief that humans, aided by technology, can expedite the process of evolution.

“We’ve outpaced natural selection, and we’re now in a time of self-guided evolution,” Reggente tells me one Tuesday afternoon. “With DNA, we can take matters into our own hands rather than relying on entropy.”

As such, operators in the space are often forging into uncharted scientific territory, pulling from research in disparate, seemingly unrelated fields.

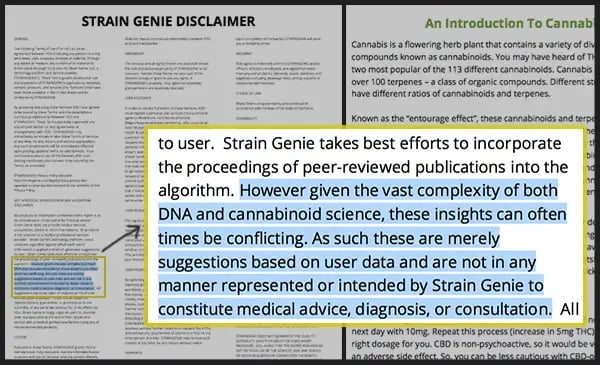

Strain Genie’s DNA test works by analyzing 150 SNPs (genetic variations in our DNA) that are, in some way or form, connected to academic research on the effects certain cannabinoids and terpenes have on medical conditions, memory, and physical activity.

My report, for instance, identifies a combination of gene variations linked to an elevated risk of Alzheimer’s disease; in turn, it recommends weed strains high in α-pinene, a terpene which “has been shown to increase memory.”

This link drawn from several dozen research papers — one of which is a study published in an alternative medicine journal that was once described as an “unethical scam” and “complete rubbish” by one of its founding editors.

This is only one of many peer-reviewed studies included in Strain Genie’s algorithm. But it does raise questions about the efficacy of certain scientific links.

The report breaks down weed strains into 6 categories, based on their primary effect(s) on most people: Chill, Medicate, Active, Sleep, Energize, and Create. According to my genetic makeup, I’m best suited for weed in the Medicate and Chill categories — products with a 2:3 ratio of CBD:THC.

It shows me glorious pictures of strains like ‘Corleone Kush’ and ‘Golden Nugget.’ Then, like a well-oiled sales funnel, it directs me to the WoahStork platform to spend money.

The DNA-ification of everything

Strain Genie is one of hundreds of niche direct-to-consumer DNA tests that have emerged in recent years.

Piggybacking on the success of popular genealogy/medical tests like 23andMe and AncestryDNA (and fueled by loosened FDA regulations), the long-tail DNA market offers gene-driven insights applicable to every facet of life.

There are DNA tests that claim to help you find the right roommate, identify personalized skincare regimens, customize your nutrient intake, identify which sports your child will excel at, and determine how good you are at skiing.

Orig3n, based in Boston, offers a “Superhero” DNA test that claims to “to leverage genetic data” to “tap into your hidden superpower,” identifying genotypes associated with superior strength, intelligence, and speed.

There are even entire platforms dedicated to hosting “DNA apps.”

For a one-time fee of $80, Helix will sequence your exome (a 22k-gene chunk of your genome), store your data in the cloud, and allow you to purchase a variety of tests that give you “unique insight” into your health, wellness, and lifestyle.

The platform boasts tests from more than 25 partners, ranging from Vinome (which recommends wine varietals based on DNA) to DNAFit! (which offers personalized diets attuned to the idiosyncrasies of your genetic code).

“We like to think of ourselves as an Apple store for DNA,” Elissa Levin, the company’s Senior Director of Clinical Affairs and Policy, tells me.

Her philosophy, shared with many others in the space, is that these tests can provide immense educational value — even if the science behind them isn’t yet as advanced as we’d like it to be.

“Let’s not be paternalistic and exclusionary with genetic information,” she says. “Our marketplace is full of all kinds of things that can make me better understand who I am and the decisions I make.”

But many experts say there’s a glaring problem with all of this…

“It’s pseudoscience — complete and utter nothing”

Those are the words of Eric Topol, a leading geneticist and a Professor of Genomics at The Scripps Research Institute.

“It’s a jungle,” he continued, in an interview with the MIT Technology Review. “It’s the mix of things that are proven and unproven that is really irresponsible, in my view.”

Topol is among a platoon of noteworthy academics who have publicly questioned the legitimacy of the science behind these “DNA-for-everything” companies. Their concern? We really don’t know that much about the broader consumer applications of DNA — certainly not enough to reliably recommend wine varietals or weed strains.

Though genetic research can tell us things like which genes are associated with higher rates of Alzheimer’s, dissenters claim that linking these findings to the benefits of a certain cannabis strain stretches the limits of reliable science.

“There is pretty much [zilch] data to support that,” Debra Mathews, Assistant Director at the Johns Hopkins Institute of Bioethics, tells me over the phone.

Mathews has a theory as to why niche DNA tests are suddenly ubiquitous: “Cool, sexy, new science is a good marketing angle.”

You don’t have to look far to see her thesis at play: During the emergence of stem cell research, skin care companies seized on the term “regenerative,” and vastly oversold the benefits of a technology that was still unplumbed.

Today, startups that have nothing to do with Artificial Intelligence routinely drop “AI” in their marketing promos. The same can be said of the “Uber for X” explosion, or the universal adoption of the term “blockchain,” which, at one point, was a fool-proof way to raise billions in capital.

Entrepreneurs often ‘sell’ science before it is fully understood: Under the guise of “democratizing knowledge,” they maul, twist, and bastardize buzzwords to sell products.

Certainly, there are many legitimate applications of DNA on the consumer market, but this legitimacy is often waterboarded by a tidal wave of marketers who overstate our current understanding of genetics in a bid to market their wares.

Reggente maintains that Strain Genie is not among these ranks.

“There are a lot of scams out there, people taking advantage of new science, and the burgeoning market of direct-to-consumer DNA tests,” he says. “We’re different. All of us here — we’re all scientists.”

A security expert’s “worst nightmare”

The niche DNA test boom has another elephant in the room: Privacy concerns.

Jen King, Director of Consumer Privacy at Stanford University’s Center for Internet and Society, calls these companies her “worst nightmare.”

“A lot of the data we share online is expirable, in some sense,” she says. “Your shopping habits or your basic demographic data change over time. Your DNA never changes. It literally has an infinite shelf life — and it’s uniquely identifiable in a way that no other personal data is.”

Representatives from both Strain Genie and Helix assured me that they have strict security measures in place and don’t sell data to 3rd parties (their privacy statements confirm this). But nothing is preventing them, or others in the space, from sharing it in the future.

Federal law only bars employers and insurance companies from discriminating based on your DNA; corporations are fair game.

“A lot of these crazy startups aren’t going to be around forever,” says King. “What happens to those databases when they go out of business? They get sold — usually to a bigger company. Would you want Amazon to have your DNA? Facebook?”

None of this was on my mind when I sent my genetic data to Strain Genie.

At best, I figured I’d learn a bit about the underlying chemical systems of cannabis; at worst, I’d get a flimsy report with little explanation of the relationship between my DNA and the “individualized” recommendations it implored me to buy.

In the end, I got both.

Like most things on the market, these genetic tests offer a melting pot of vaguely educational content and complete nonsense.

Or, as my good friend, a Harvard-trained geneticist, analogized via text: “These tests are like toilets: They collect DNA, but sometimes they’re also full of shit.”