Twenty years ago, Pizza Hut was an innovation powerhouse.

It employed food scientists who patented crusts that didn’t break down when mixed with garlic and trotted out blockbuster products like BigFoot, the Edge, and the Triple Decker. When the chain launched Stuffed Crust in 1995, the stock for Pepsi, its then-parent, increased about 50% over the next year; the Big New Yorker, released 4 years later, led to a 9% rise in same-store sales.

Wild, innovative pizzas made markets move.

But today, Pizza Hut rarely offers new items. In recent years, the best it’s managed to do is change the cheese in its Stuffed Crust from mozzarella to cheddar, or trot out an occasional, ill-fated appetizer like the Stuffed Cheez-It.

In 2017, Pizza Hut’s parent company, Yum Brands, spent ~$22m in research and development — $10m less than it spent in the pizza golden age of the ‘90s, accounting for inflation. That same year, Yum invested $130m for pizza delivery technology and related marketing.

In a country where a new chicken sandwich can break the internet and where Taco Bell can sell 100m Doritos Locos Tacos in 10 weeks, culinary innovation in fast food pizza has been stagnant. Can Pizza Hut thrive when people only care about the convenience of ordering?

The rise of the Hut

Growing up, I was chain pizza’s perfect customer.

I was a landlocked Kansan who wouldn’t visit New York City (where far tastier pizzas exist on nearly every street corner) until after my 18th birthday. My family ordered pizza almost every Wednesday night, mostly from Pizza Hut, occasionally from Domino’s (in the days before they admitted their pizza sucked), rarely from Papa John’s, and perhaps once from Little Caesars (it was cold and the pepperoni was undercooked).

Outside of New York, Philadelphia, and other East Coast pizza hotbeds, these non-coastal chains had a captive audience in us Midwesterners, and families like mine turned them into big business — especially Pizza Hut. It was the original chain and, in the mid-90s, had a 25% market share of nearly the entire pizza restaurant industry.

At the time, pizza restaurants were uncommon in much of the US. But there was an underserved need — and the Carneys started franchising elsewhere in Kansas within a year.

Pizza Hut was founded in 1958, in Wichita, three hours from my hometown in the Kansas City suburbs. Brothers Dan and Frank Carney pooled together $600 to open the first restaurant in a modest brick building not far from Wichita State University. They soon established rapport with inebriated college students.

When they settled on their trademark look of brick restaurant with a red roof in the 1960s, Pizza Hut grew even further. By 1973, the brand was selling $225m in pizza annually at nearly 1,800 stores.

The Carneys were touted as business savants, and, in a pre-tech world, franchisees were considered daring entrepreneurs.

In 1961, The Arizona Republic gushed about Chuck Misfeldt, an engineering student at Arizona State who decided to open a Pizza Hut instead of opting for a traditional career path: “He’s proving that the American pioneering spirit isn’t dead. Misfeldt is an exception to the rule these days that youth seeks job security and comfortable pensions rather than taking a chance.”

In small towns, like where my great-grandmother lived, the Pizza Hut, with that welcoming red roof, signified its status as the most dependable restaurant in town. Once a month, if elementary school children like me read enough books, we’d get a personal pan pizza through the Book-It program.

Most of all, in a market where Domino’s was known for speed, Little Caesars for bargains and Papa John’s for quality ingredients, Pizza Hut became known for its wild innovations.

The innovation age

The idea for pizza reinvention came from David Novak, who was hired in the 1980s as the head of marketing to block the growth of Domino’s and Little Caesars.

Novak reasoned that new products drove top-line sales, that they enticed more people to purchase the pizza and would keep many of them coming back. But the dozens of food scientists employed by Pizza Hut at the time focused on quality control and engineering.

So Novak started a new product development team that fused a marketing savvy with a scientific background to make wild new concoctions a reality.

His edict was that Pizza Hut needed to release a new invention approximately every six to eight weeks. Considering new pizzas had to be tested for at least 18 months, this required an astonishing level of planning.

At first, the burden fell to a handful of employees, led by Tom Ryan, who would go on to found Smashburger. Patty Scheibmeir, two weeks after graduating from Kansas State University, started working with the new product development team in January 1990. She was the third hire.

As a recent college graduate, her job, at first, was the food science equivalent of coffee fetcher: Ryan and others would say, “Patty, go make some pizzas,” she recalls, and Scheibmeir would shove whatever concoction they had brainstormed into one of the ovens in the Wichita headquarters’ expansive test kitchen.

Most ideas — pizza in a cone, waffle crust pizza — fizzled long before the general public got a taste. Early breakthroughs included barbecue and a cheeseburger pizza, which were unheard of at the time, and the “Lovers” line (Meat Lovers, Veggie Lovers, etc.). This success prompted the company’s COO to visit Ryan in his office.

“He said to me ‘Well, you’re in trouble.’ And I’m like, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because everything there is to do with pizza, it’s now been done,”’ Ryan recalled in an interview with the food website First We Feast. “It made me a good kind of angry.”

The new product team dug further. They patented a crust recipe to prevent garlic from breaking down pizza dough in the Sicilian Pizza. For The BigFoot, Pizza Hut introduced one of the largest pizzas ever seen: 2 feet long and 1 foot wide, with square slices.

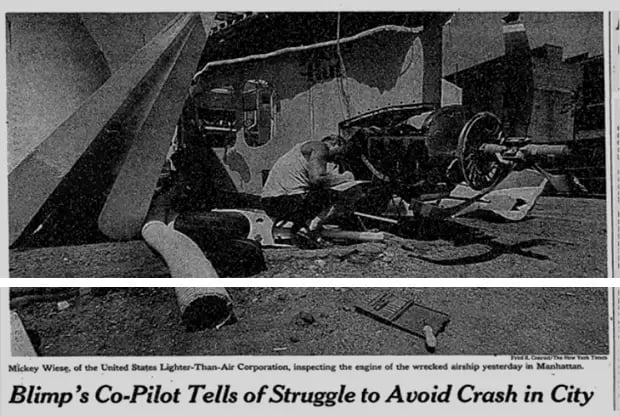

It was a phenomenon: A young Haley Joel Osment appeared in a BigFoot ad, and a $4m BigFoot blimp was deployed to win over the tough East Coast. (Alas, it crashed into an apartment building in 1993; a Pizza Hut VP deadpanned that the disaster had probably “heightened brand awareness.”)

The new development group that had started with three employees had, according to The Wichita Eagle, grown to 60 by 1994. Scheibmeir quickly moved up. Within a few weeks, she was traveling across the country to survey focus groups.

At one of the groups, an odd middle-aged man kept talking about pizza bones: He would eat the pizza and leave behind the “bones” for his dog. Asked for clarification, he said the bones were the crust. Nobody ate the crust.

The idea came so fast that Scheibmeir had to jot it down on the paper plate sitting in front of her. Later at the grocery store, she bought packets of string cheese that she placed in the crust in the test kitchen the next day.

During the next couple years the food scientists had to patent a new recipe for a crust that wouldn’t split open, and anxious management, Scheibmeir says, temporarily killed the experiment 13 times, including three months before the proposed rollout.

But the Stuffed Crust proved so popular that its first limited six-week trial sold out in four weeks, Scheibmeir says. Sales of Stuffed Crust reached $1B in the first year, helped in part by a commercial featuring Donald Trump and his first ex-wife, Ivana.

“After that everybody was waiting for the next innovation from (Pizza Hut),” Scheibmeir says.

The Edge, the Triple Decker, the P’Zone and the Big New Yorker all came after Stuffed Crust and were credited with spurring sales growth every year in Yum Brands’ annual reports. But the innovations started fading away in the aughts.

In 2009, the big chains were hit hard by a recession-induced spike in frozen pizza popularity.

Sales at Pizza Hut declined by 12% in the fourth quarter of 2009 compared to the same period the previous year. Winning back customers was less about taste and new products and more about making pizza reliable— and easier than the Tombstone tempting customers in the frozen goods aisle.

Convenience was never Pizza Hut’s strong suit. Although the chain beat everyone to the internet (the company claims to have sold the first physical good online, in Santa Cruz, CA), Domino’s has long offered better technology.

In 1994, Domino’s was developing a website that let customers drag virtual toppings toward an onscreen pie. Pizza Hut’s service merely transmitted typed orders to a center in Wichita before routing them back to Santa Cruz. But what did it matter? As Stanford economist Nathan Rosenberg opined that year, the push to bring pizza delivery online was an instance of “sophisticated technology being put to trivial use.”

He was wrong: Online delivery is now the most important part of the pizza business.

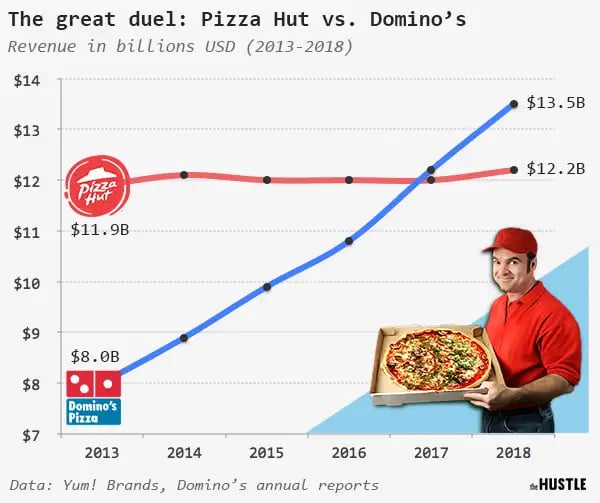

Post-recession, in the 2010s, Domino’s outdid Pizza Hut and everyone else with a superior delivery app and website. Then it introduced ordering via Twitter and Facebook Messenger and a fleet of DXP cars. Domino’s didn’t have to use food to entice customers. Technology was enough.

Last year, Domino’s, which made about $13.5B worldwide, surpassed Pizza Hut as the pizza industry leader for the first time, with 15% of market share.

In today’s pizza ecosystem, fast-casual chains like Blaze, Pie Five and Mod have been experiencing ~100% year-over-year sales growth. Blaze expects to have 1,000 stores in the next seven years. Scheibmeir now works for Pie Five as vice president, research & development & product innovations. One of her most recent innovations was a pizza with a cauliflower crust that, she says, “has been selling like crazy.”

The fast-casual restaurants have cultivated a reputation for fresh ingredients, allowing them to test new ideas in a way Pizza Hut no longer can.

“When delivery, convenience. and price are your biggest concerns, you turn to one of the big chains,” says Rick Hynum, editor-in-chief of PMQ Pizza Magazine. “When you want an artisanal pizza and a real dining-out experience with a capital E, you go out to eat at a nicer casual or fine-dining place, and that’s where you expect to find culinary innovation.”

One of Pizza Hut’s last wild new offerings was a pizza with mini cheeseburgers for the crust, released outside of the US. It went over poorly. The Guardian described the product as the poster-child of an impending global food crisis.

In 2014, Pizza Hut also introduced a new menu that declared customers could purchase a pizza with 2B possible flavor combinations, including balsamic and sriracha drizzles. The new varieties were mostly variations of well-known pizzas, except with awkward yet trademarked names like Skinny Beach and Pretzel Piggy. These pizzas or drizzles can no longer be found on the restaurant’s website.

Pizza Hut’s decline in innovation reminds Bret Thorn, senior food & beverage editor for The Nation’s Restaurant News, of an anecdote about Applebee’s.

Against its better judgment, Applebee’s once considered selling three-cheese lasagna, introducing the dish at a focus group. At first, the participants expressed excitement. Then, when it was revealed the three-cheese lasagna was made by Applebee’s, their opinions changed. They wanted nothing to do with it.

“You have to have the reputation of being good at what you’re innovating in,” says Thorn.

Make pizza great again

Flustered by Domino’s in the delivery game and fast-casual restaurants in the quality game, Pizza Hut has tried everything the last few years.

The brand has invested in a self-driving vehicle. It took over from Papa John’s as chief pizza sponsor of the NFL. This summer, it announced it would close 500 dine-in restaurants and has also redesigned many others. Its latest delivery-related innovation is a round pizza box.

The results, so far, have been mixed.

Same-store US sales were basically flat last year, and a modest sales increase this year has been tied to many Pizza Huts offering beer delivery. And the golden Domino’s strategy could be ending anyway. With Postmates and DoorDash bringing delivery everywhere, its same-store sales and stock growth have slowed this year.

The internet is replete with nostalgia for Pizza Hut’s better days. The hashtag #BringBackBigFoot pervades Twitter, and 1,100 people have signed a Change.org petition for Pizza Hut to resurrect The Big New Yorker.

A Pizza Hut representative declined to make any of the chain’s leaders available for this story.

In an earnings release conference call last year, Yum chief executive Greg Creed said, “The opportunity for us is to bring in new customers by communicating and messaging better this compelling new proposition that Pizza Hut US has to offer, which is an operating improvement, an ease improvement, a value improvement.”

About the only thing he and other executives haven’t publicly discussed is pizza, which Scheibmeir insists is still ripe for innovation.

“There’s going to be something out there, somebody’s going to go, ‘Why didn’t we think about that before? And it’s going to be one of those no-brainers. I don’t know what it is but somebody will think of it.”