On March 20, 1823, after 2 grueling months sailing across the Atlantic Ocean, passengers gathered on the deck of the Kennersley Castle for the first glimpse of their new lives in the country of Poyais.

The view was immaculate: Sun glistening in the shallow waters of a blue lagoon. Mahogany trees drooping over sandy beaches.

James Hastie, who was moving to Poyais with his wife and 2 children, thought the country “had a very beautiful appearance from the sea.”

Like many passengers, Hastie had signed a contract with the Poyaisian government to work as a laborer. Others, including doctors and lawyers, had cashed in their belongings in Europe for land in Poyais and the opportunity to establish themselves as a new upper crust in the Caribbean.

Rich or poor, it seemed impossible not to prosper. The myriad Poyais advertisements that circulated through Britain had promised fertile land, rivers stocked with fish, and forests teeming with deer.

But as Hastie and the others soon discovered, Poyais was not a country at all. It was one of the most elaborate — and deadliest — frauds in history.

The rise of a scammer

Raised by a privileged Scottish family on the periphery of the aristocracy, Gregor MacGregor tasted enough wealth to know how good it would feel to have more.

MacGregor went to top schools and, at 16, he joined the British army, a haven for status-seeking young men. But his real coup was winning the heart of Maria Bowater, a daughter of a navy admiral who ran in Britain’s finest social circles.

A portrait of a young MacGregor in the British army (George Watson/National Gallery of Scotland/Wikipedia; 1804)

Armed with Bowater’s family wealth and prestige, military life suddenly got easier for MacGregor.

He paid £900 (~£72k today) to become captain of his regiment — a promotion that would have otherwise taken several years — and was on the fast track toward general, the highest distinction in the army.

But the money didn’t make MacGregor competent at his job. After a fight with a superior officer, he was forced to resign.

Then, in 1811, Bowater died, and her embarrassed in-laws cut off MacGregor from their fortune. His supply of old money gone dry, MacGregor seemed destined for obscurity.

And yet he managed to fail upward.

After spending several years as a hapless leader in Venezuela’s revolution against Spain — which included deserting his troops during 2 key battles — MacGregor returned to England in 1821 with instant credibility because of his ties to the decorated politician Francisco de Miranda.

It also helped that he married rich again, this time to a cousin of the famed revolutionary Simón Bolívar. The duo became a power couple, wined and dined by London’s lord mayor.

MacGregor stikes another pose for an 1825 portrait (Samuel William Reynolds/Simon Jacques Rochard)

Not everyone was swooning.

In 1820, the brother of one of MacGregor’s charges in Venezuela released a 418-page book that detailed MacGregor’s military mishaps, more or less eviscerating him as a leader.

“That any person could be induced again to join him in his desperate projects,” wrote Michael Rafter, “would be to conceive a degree of madness and folly of which human nature, however fallen, is incapable.”

Unbeknownst to Rafter, MacGregor had a cunning trick up his sleeve.

The dot-com bubble of the early 19th century

In 1820s England, no phrase excited investors more than “South America.”

Britain was swimming in cash and optimism after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. But there was no more war to finance, and the interest rates of the most popular British-backed securities declined, tempting the record numbers of people trying to time the market for maximum profit to find something stronger and riskier.

South America — a catch-all for what is now Latin America — was the inevitable target.

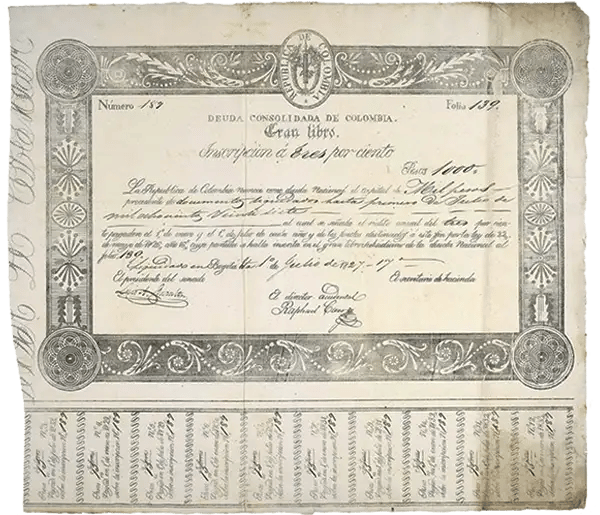

Several countries had gained independence from Spain and were floating bonds to finance their incipient governments. Countries like Colombia and Chile sold bonds totaling ~£100m-£200m in today’s money, promising 6% in annual returns by tapping into profits from state-run agriculture and mineral industries.

So began a craze akin to the dot-com bubble: Investors who knew basically nothing about the inner workings of South American countries went on a buying spree, inflating the value of the bonds and creating an intense resale market.

A one-thousand peso Republica de Colombia bond from 1827 (PGM)

In this speculative environment, MacGregor crafted an insidious plan.

During his South American misadventures, he’d befriended George Frederic August I — the king of the Mosquito Coast Territory (present-day Honduras and Nicaragua) — and had been gifted 8 million acres on the eastern shore of Honduras, an area roughly the size of Maryland.

The land belonged to MacGregor, but it was under the dominion of the British-aligned Mosquito government. Of course, nobody in Europe knew these details.

So back in London, at various society events, MacGregor presented his land as the independent country of Poyais — and cast himself as the ruling “Cazique.”

In short order, MacGregor set about marketing the territory as a real country:

- He designed a national flag and a coat of arms for Poyais featuring two unicorns.

- He got British papers to detail bond prices for Poyais just as they did for legitimate countries.

- Outside offices in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and London, he and his representatives handed out brochures and sang songs about Poyais.

To top it off, there was a book about Poyais that concluded the new country “would rapidly advance in prosperity and civilization.” (This ruse perhaps should have been obvious — the pseudonymous author’s name was “Thomas Strangeways.”)

MacGregor advertised Poyaisian land and estates in papers throughout Scotland and England. (Via Newspapers.com/The Caledonian Mercury)

As 1822 wore on, the excitement spread, and MacGregor steadily increased the price of land from 1 shilling per acre to 4 shillings per acre (£6 to £24 per acre today). In the fall, investors snapped up £200k of bonds (~£24m today) at a 6% rate of return.

They believed they were financing a building boom in a developing country. In reality, the money lined MacGregor’s pockets.

There was just one major concern, according to David Sinclair’s book The Land That Never Was: How would Poyais pay the interest?

Without any current revenues to describe, MacGregor assured the investors that funding would come from future inhabitants.

This meant Poyais needed settlers — and fast.

Fortunately for MacGregor, hundreds of British had fallen for the marketing hype, exchanging their life savings for Poyaisian money and land grants. The first ~70 settlers left from England in fall 1822 on the Honduras Packet. Another ~180 set sail from Scotland in January 1823 on the Kennersley Castle.

Before the 2nd group departed, MacGregor greeted them aboard the Kennersley Castle and offered free passage for all the women and children. The future Poyais residents were elated at his generosity.

“We gave him a salute of 6 guns and 3 cheers,” Hastie recalled in his memoir. “Little did we anticipate the misfortunes which were afterwards to befall us.”

Death at Poyais

After the beautiful view from the ship, Hastie and the others believed they would find St. Joseph, a European-style capital city outfitted with a government center and a theater.

Strangely, the new arrivals didn’t see any dwellings or buildings. The only signs of life were the remaining passengers from the Honduras Packet, holed up in bamboo huts, and 2 eccentric Americans who had been living off the land for years.

There was no property to be assigned to the landowners. No banks for depositing and withdrawing Poyaisian money. No easy access to wild game.

The supposed location of Poyais (Johnson)

Over the next couple months, the Poyais newcomers felt the consequences of the punishing heat and humidity, withering away from hunger, exhaustion, and malaria as they rationed provisions from the ship.

One leader swindled by MacGregor, Hector Hall, and a Belizean general organized trips between Poyais and Belize, rescuing ~100 people whose health hadn’t completely deteriorated.

They also sent word to Britain that Poyais was a scam, leading the Royal Navy to intercept 5 more ships headed toward Poyais.

In October 1823, ~50 of the Poyais settlers arrived in Britain, including Hastie and his wife. Hastie’s 2 children did not survive, and fewer than ⅓ of the settlers who had arrived in Poyais in the previous year made it back alive. Those who did were in critical condition.

“They had evidently undergone extreme suffering and illness, as their appearance was ghastly and cadaverous,” wrote one Scottish newspaper.

MacGregor’s scheme — and the entire British economy — were on the verge of collapse.

The bubble pops

As the victims of his fraud suffered, MacGregor threw ragers in London.

One guest remembered being asked at a party to take an oath to Poyais, only to find it impossible to recite the words in their drunken stupor, “from… the wine having passed very freely round.”

But MacGregor’s celebration was short-lived.

South American bonds faltered in the middle of his Poyais scheme because the countries that sold their bonds spent the proceeds on military conflicts, failing to pay back their debts. Many investors grew skeptical of Poyais by association — even before knowing it was fake — and declined to pay the new installments they owed for their bond purchases.

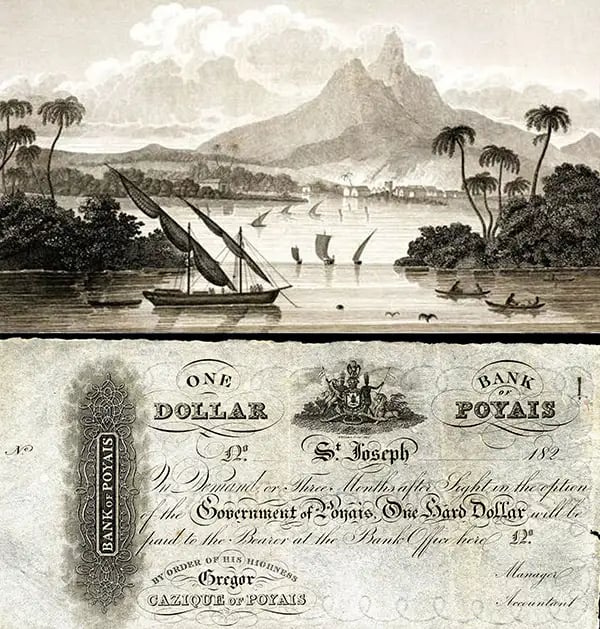

Top: A fictional illustration of Poyais (Chronicle Books); Bottom: A one-dollar note issued by the Bank of Poyais, Republic of Poyais (WIkipedia)

MacGregor had spent enormous sums on marketing, on voyages to the fake country, and on his own extravagant lifestyle. When the bond payments ended, his cash flow trickled to nothing.

The Poyais fraud was extraordinary because of the suffering and death it inflicted upon more than 200 would-be settlers. But the financial repercussions were hardly unique.

The South American bond bubble popped, contributing to the Financial Panic of 1825. By 1827, nearly every Central and South American bond issue had gone into default. In the aftermath of the panic, 52 English banks failed.

As with bubbles and scams today, it was the average British person who fared the worst.

Wealthy insiders got in on South American bonds at the earliest stages and lowest prices. Regular investors paid the higher prices, only to sell them for a fraction when the bonds didn’t pay out.

The few people who held onto their bonds made some money back when South American countries stabilized and started making interest payments in the 1840s and 1850s. Of course, if they invested in Poyais they never saw a dime.

- It’s likely at least ~£3.6m in today’s money was lost because the down payment owed on the £24m of bonds sold was 15%, according to Sinclair’s book.

- MacGregor also sold ~500 grants of land (for amounts such as 100 acres and 1k acres) and bilked investors and settlers out of untold amounts of British pounds exchanged for fake Poyais currency.

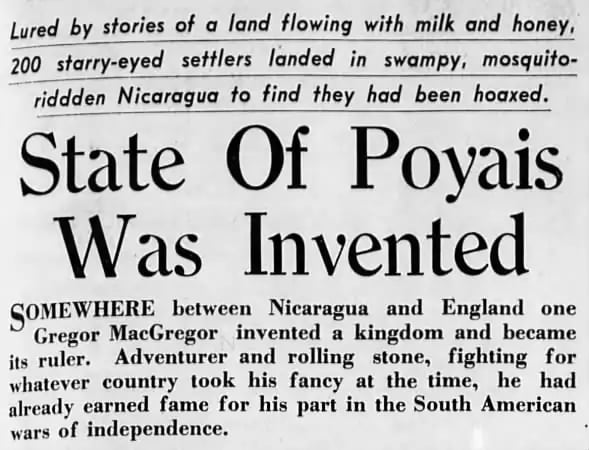

News of the scam spread quickly (a later headline from the Newspapers.com archives)

Knowing more trouble lay ahead as his victims returned, MacGregor fled to France. He escaped prosecution for his fraud and tried selling land in Poyais twice more before retiring to Venezuela.

And a peculiar thing happened when the Poyais survivors got back to Britain. Despite MacGregor organizing the scam and causing the deaths of their loved ones, they didn’t blame him.

In fact, when Hastie and several other passengers from the Kennersley Castle read news coverage about Poyais, they were angry. They strode into the Mansion House, a seat of the London government, and signed an affidavit stating they believed MacGregor had done nothing wrong. That he was a victim as well.

And so, the scam ended as so many do, with the charismatic con artist getting away unscathed.