Three months ago, Jalea Pippens — a phlebotomist at St. John Hospital in Detroit — had her hours cut.

In the midst of the pandemic, the 23-year-old found herself in dire need of a second income stream. One night, while scrolling through search results for “ways to make extra money,” she came across vending machines.

The daily minutiae of owning a vending machine seemed a bit dull: buying bulk candy at Sam’s Club, stocking machines, collecting weathered bills and buckets of coins. But Pippens saw an opportunity to be her own boss.

She partnered up with her boyfriend and another business partner, bought a vending machine on Facebook Marketplace for $1.6k, and plunked it down at a local auto parts store, where it now grosses $400 per month.

“I’d never really thought about vending machines,” she tells The Hustle. “I didn’t even know you could own one.”

Pippens is one of thousands of individual operators who make up the bulk of the vending machine ecosystem.

During the pandemic, the relatively low barrier of entry has attracted a new generation of vending machine entrepreneurs — schoolteachers, nurses, mechanics, students — who measure profits in $1 bills and utilize new technologies to monitor and scale their operations.

But are vending machines really a viable side hustle? How much does the average machine bring in? And what does the job entail?

To find out, The Hustle surveyed and interviewed 20+ vending machine operators all over America.

A glimpse at the market

It is estimated that roughly ⅓ of the world’s ~15m vending machines are located in the US.

Of these 5m US-based vending machines, ~2m are currently in operation, collectively bringing in $7.4B in annual revenue for those who own them. This means that the average American adult spends ~$35 per year on vending machine items.

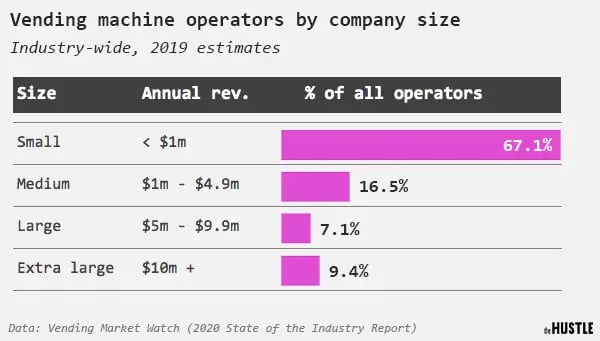

What makes the vending industry truly unique is its stratification: The landscape is composed of thousands of small-time independent operators — and no single entity owns >5% of the market.

(Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Some big corporations, like Pepsi and Coca-Cola, own their own arsenal of machines. But vending requires so many moving parts and brings in such slim profits per machine that it’s better suited for smaller operators who can minimize overhead costs.

According to a 2020 IBISWorld report, the nation’s 2m in-use machines are owned by 17.6k small businesses, the vast majority of which employ just a few people.

The vending industry is broad and encompasses everything from $0.50 gumballs to — well:

- Live hairy crabs (~$4 each)

- Beluga caviar ($500 per ounce)

- Engagement rings ($800)

- Live earthworms for fishing ($3.50 for a dozen)

- Morning-after pills ($25)

- COVID-19 essentials like hand sanitizer and masks ($4.25 to $14.50)

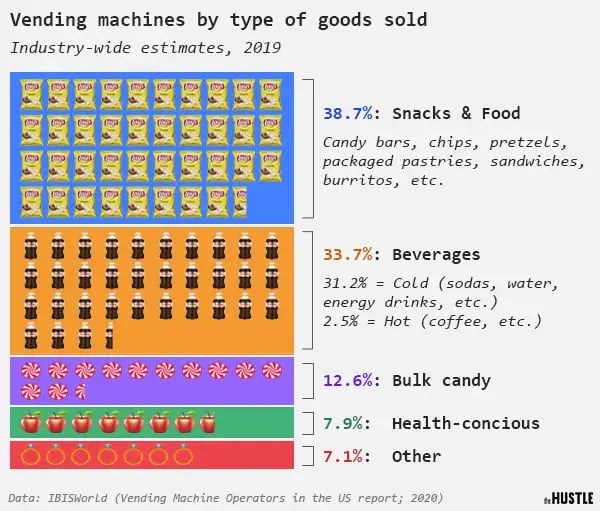

Oddities aside, the majority of vending machines (72.4%) house standard snacks and beverages — what are known as “full-line” machines in vending parlance.

(Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Several things attract new operators to vending:

- Relatively low startup costs: An operator can find a decent machine and buy inventory for <$2k.

- Scalability: Early revenue can be reinvested in expansion to leverage economies of scale.

- A largely passive routine: Restocking and cash collection can be reduced to a few times per month.

- A flexible schedule: Like the gig economy, vending allows operators to set their own hours.

But starting out in the business comes with its share of hurdles — the first of which is finding the right machine.

A new machine straight from a manufacturer can run from $3k to $8k+ — though used machines can be purchased on Craigslist or Facebook Marketplace for as little as $300.

As Paul Valdez, a 39-year-old Miami operator, learned, those machines often end up being more trouble than they’re worth.

“I bought 4 machines on Craigslist for cheap and fixed them,” he tells The Hustle, “but they were all so crappy and old that no business wanted them.”

Once an operator like Valdez has secured the right machine, the next obstacle is finding a quality home for it.

Location can make or break a machine’s success — and finding a good one is often a steep challenge for people who are new to the business.

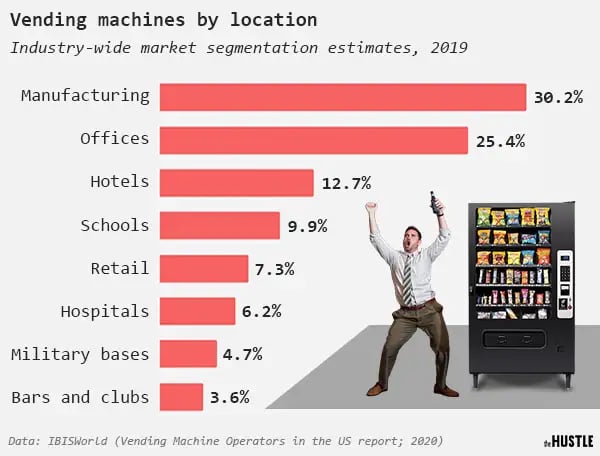

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Many of the best locations — places with heavy foot traffic, or large worker populations — are already saturated with machines.

Some owners we talked to have to make 100+ calls before landing a decent location. In the end, they often end up paying the owner a commission of 10%-25% of gross sales to drive home the deal.

Other owners resort to buying pre-established “routes” — machines that are already placed on-site somewhere — or attempt to knock out existing operators by offering a better service.

“It can be dog-eat-dog,” says Alyssa Howard, a 28-year-old who owns 22 snack machines in Colorado. “You have to treat it as a zero-sum game.”

The reason for this competition is simple: There is a tremendous variance in how much revenue a machine can bring in, based on where it is.

Good margins, small volumes

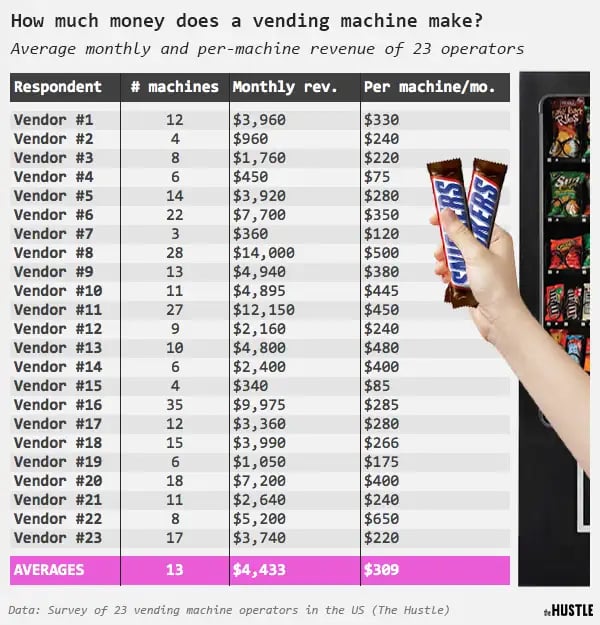

We surveyed 23 vending machine owners with various-sized operations and found that the average operator in our sample owned 13 machines that gross $309 per machine per month.

But self-reported revenue per machine per month ranged from just $75 to $650.

Note: This data comes from a survey of 23 operators and isn’t meant to be definitive; some vending machines make far less than the figures listed here; others make far more. (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Most vendors we spoke with noted big differences in revenue across their own machines.

“I have one machine that does $25 every 2 weeks, and another that does $600,” says Everett Brown, a 32-year-old Lyft driver from Minneapolis who vends part-time. “Every location is different; some places suck, and others are gold mines.”

Jaime Ibanez got into vending in 2018. Fresh out of high school, he dropped $2.5k — about half his savings — on a refurbished snack machine and found a home for it at a local barbershop in Dallas.

Today, he owns 35 machines that gross $10k in revenue every month. His best location, a hotel, earns him $2.8k; his worst sometimes only sees $200.

And remember: these figures are pre-expenses. The business comes with its share of overhead costs.

For starters, ~50% of revenue goes toward the cost of items that go in the machines.

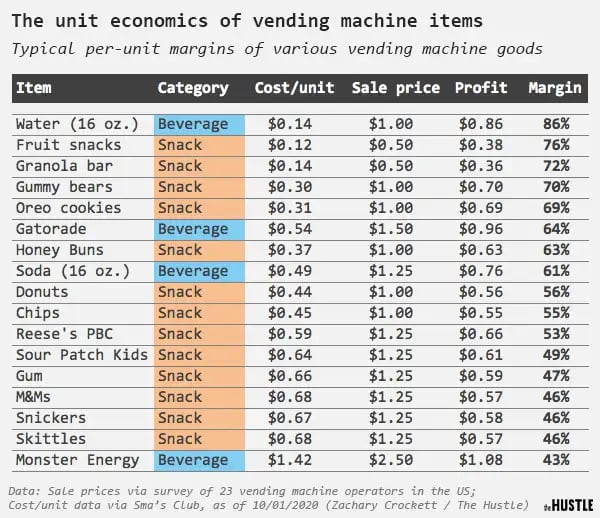

Many operators buy their wares in bulk at Sam’s Club and Costco and sell them for roughly 2x the price they paid. Here’s a look at how a typical vending machine’s margins might look by item:

(Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Among the other operating costs reported by vending machine owners:

- General liability insurance (~$500/yr for <$100k in annual sales)

- Commissions paid to locations (5-25% of revenue)

- Transaction fees for card purchases (~5-6%)

- Card reader analytics fees ($10/mo)

- Storage space for unused machines (~$100/mo)

- Gas and transportation ($50-$100/mo)

- Taxes (10-37% of adjusted gross income)

- Routine maintenance and vandalism repairs ($50-$250/yr)

Even something like logistics can be a burden: Vending machines are extraordinarily heavy — 600-800 lbs. — and often require special equipment to pick up and move.

All costs considered, an operator who makes $5k per month in revenue might take home something like $2k in profit.

To make vending work as a full-time gig, an operator typically must implement economies of scale, building the business up to dozens of machines that collectively generate a livable wage.

Operators like Ibanez are constantly reinvesting in expansion.

Ibanez with a few of his 35 vending machines in Dallas (via Jaime Ibanez)

The biggest input cost of all — the amount of time a vendor spends on-site — has been minimized by technology in recent times.

“I can visit all my machines in 2 days and not have to go back for 2 weeks,” says Ibanez.

Twenty years ago, operators had to drive to each machine on a semi-daily basis and jot down the items they needed by hand. Today, telemetry tools have largely allowed newcomers to operate remotely.

Roughly 70% of today’s vendors use some form of tech (card readers, apps, iPads) to monitor sales and inventory in real-time.

On a typical site visit day, Ibanez will get up at 6am, check his apps for inventory, and load up on his bestsellers — Honey Buns, M&M’s, and Snickers — at Sam’s Club. After restocking, collecting money, and doing an occasional repair, he’s home by 4pm.

This seemingly dull routine has piqued the interest of hundreds of thousands of young entrepreneurs on the Internet.

Ibanez’s YouTube channel, which chronicles his life as a vendor, boasts 362k subscribers and now earns more than his machines.

“People love to see the stacks of cash getting pulled out,” he says.

But something else is driving this fascination: the allure of a semi-passive income has led to a spike in vending during the pandemic.

The COVID-19 boom

Barry and Lori Strickland, a married couple in San Diego, run The Vending Mentors, an educational resource that offers an online course ($297) and ongoing consulting services ($97/mo) for new vendors.

Their journey into vending began back in 1989, when Barry — then a 30-year-old special education teacher — bought a few machines to make extra income during the summer.

Eventually, the couple grew the business to 250 machines and $500k in annual revenue before selling it.

Lory and Barry Strickland have seen an uptick in their vending machine course during the pandemic (Barry and Lory Strickland)

Since the pandemic, the Stricklands say they’ve seen a huge uptick in interest. This year, 200 vendors have signed up for their course.

“A lot of blue-collar workers are realizing their jobs are not as secure as they thought they were,” says Mr. Strickland. “We’re getting tons of interest from people who lost their jobs, or had hours cut, and are turning to vending to take things into their own hands.”

Mr. Strickland says that most vendors he knows have seen a 10-50% dip in revenue this year due to the stressors of the pandemic.

Radical shifts in consumer behavior, physical interaction, and health guidelines have shifted the vending landscape. Vendors who rely on schools have been hit especially hard; other locations, like nursing homes, have continued to perform well.

Despite the shakeup, Mr. Strickland maintains the market is ripe for entry.

“Vending machines are relatively safe compared to food prep — there isn’t as much human contact,” he says. “It’s also a business that a lot of people consider to be recession-proof.”

In particular, the Stricklands have noticed an uptick in Black and Latino vending machine owners — a trend they attribute to accessibility and relatively low startup costs.

VendingNation, a popular private Facebook group for new venders, has grown from 6k to 14.5k members since January — a 142% increase — and many of the new members are from underrepresented groups.

Jalea Pippens with a new machine — one of 15 she co-manages with her partners, Steven Lee and Gabriel McKinnon, in Detroit (Jalea Pippens)

Among them is Jalea Pippens, the phlebotomist from Detroit.

After buying her first machine 3 months ago, she launched Literally Lit Vending with her boyfriend (a nurse), and his best friend.

“The pandemic made us into entrepreneurs,” she says.

Over the past 3 months, Literally Lit has grown to encompass 15 machines all over Metro Detroit. Recently, they landed their biggest deal yet: 5 machines at a steel manufacturing warehouse.

Collectively, the machines now bring in $4k in monthly revenue — most of which is being reinvested into the company.

“When I used to see a vending machine at the hospital, I’d spend at least $5,” she says. “Now I’m on the other side, collecting the bills.”