Jeff Young is the Managing Editor at EdSurge. He recently launched a great 6-episode podcast series on bootstrapping, which you can listen to here.

***

It’s a badge of honor to “bootstrap” a startup, a reference to the great American tradition of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.”

The phrase evokes a rugged cowboy alone on the range, or the notion that a genius founder who answers to no one can best bring innovative ideas to life.

In practical terms, bootstrapping a company usually means starting with no external funding — no bankers or investors to muddy or distort a founder’s vision. Proponents point to category-starting companies that have bootstrapped, including GoPro, GitHub, Mailchimp, and (in its earliest days) Facebook.

And it’s cool to tell these origin stories, with the bootstrapper usually painted as an underdog maverick.

“I am a laser beam,” wrote Seth Godin in “The Bootstrapper’s Bible,” glamorizing what founders should tell themselves in their internal narratives as they go it alone. “Opportunities will try to cloud my focus, but I will not waver from my stated goal and plan — until I change it.”

Lost in all the praise of bootstrapping, though, is an inconvenient origin story.

Because it turns out the term “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps” started out as an insult against bombastic nimrods who claim they’ve achieved something that is simply impossible.

These days, the phrase is drawing scrutiny as part of a broader discussion of growing inequality in America. At least in some circles, people are wondering whether it’s fair to ask someone to pull themselves up at a time of heightened awareness that not everyone has metaphorical boots.

So it’s worth asking: Is it time for the business world to recalibrate its liberal use of “bootstrapping”?

Bootstrapping started as a joke

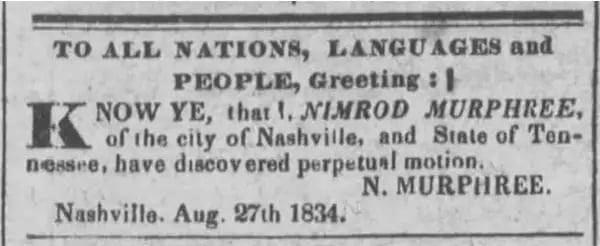

The story of the term bootstrapping begins way back in 1834, with Nimrod Murphree, an inventor from Nashville, Tennessee.

Murphree took out an advertisement in his local newspaper boasting that he had invented perpetual motion — a claim apparently common among cranks and pseudo-scientists of the day.

Nashville Banner, Aug. 27, 1834 (via Newspapers.com)

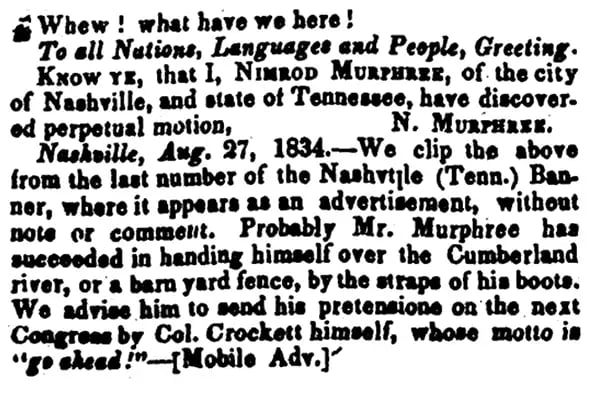

That little ad did the 19th-century equivalent of going viral.

It spread like wildfire in other local papers around the country — and just like people often share something today on platforms like Facebook so they can make fun of it, those who picked up on this ad threw in their own commentary.

“Probably Murphree has succeeded in handing himself over the Cumberland River, or a barnyard fence, by the straps of his boots,” quipped an article in a newspaper in Mobile, Alabama, mocking the inventor’s claim.

New York American, Sept. 30, 1834 (via Genealogybank)

“Basically they were making fun of this idea,” Ben Zimmer, a language columnist for The Wall Street Journal who has researched the history of the phrase, tells The Hustle.

Zimmer said the term “pulling yourself up by one’s bootstraps” “remained a ridiculous one” for decades. It was not something anyone would say about themselves.

Yet startups eventually saw it as aspirational

By the 20th century, the term pulling yourself up by your bootstraps had morphed, changing to something not only possible, but desirable.

Zimmer said it’s not exactly clear just when the turn happened, but it became a compliment about self-sufficiency.

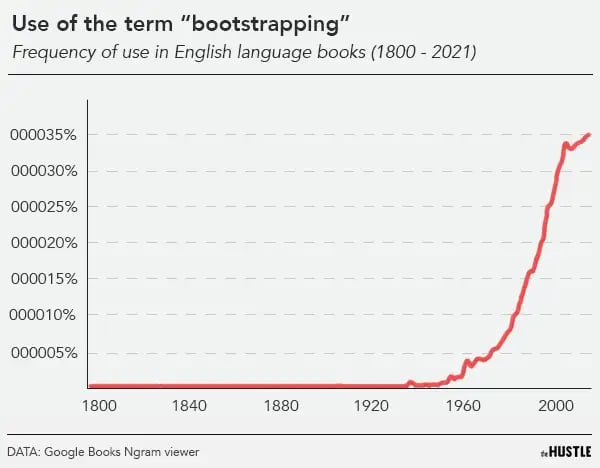

Matt Rutherford, a business professor at Oklahoma State University and author of Strategic Bootstrapping, tells The Hustle that there has been an explosion of blogs, podcasts, books and academic work praising the approach of starting a company without outside investment, just with one’s own figurative boots.

The Hustle

Few question whether the approach is valid; the choice usually presented is whether or not it’s right for a given business.

Fans of bootstrapping fall into 2 main camps, Rutherford explains:

- Those who see it as a way to avoid outside influence that might skew the original vision of the venture. (“Their perception is that a banker or an equity player is going to tell them how to run their baby, and they don’t like it.”)

- Those who are interested in the strategic value of starting with very limited resources, which supposedly forces startups to find creative solutions to problems.

When Nick Woodman was starting GoPro, for instance, he started with $10k he earned by selling belts made out of shells and beads, using his VW van as his storefront. He designed his initial product by hand because he didn’t have the knowledge or equipment to do it digitally.

But there are downsides, both moral and practical

What the standard narrative of the heroic bootstrapping CEO leaves out, of course, is the amount of privilege it takes to be in a position to go it alone.

Take Woodman’s story. He dreamed up the idea for GoPro cameras while on a solo surfing trip to Australia and Indonesia that he took after his earlier video game startup failed.

He had enough money to afford the adventure travel he was designing for, and he lived with his parents and had plenty of other help along the way (including a $200k loan from his father, the co-founder of an investment bank).

Nick Woodman famously bootstrapped GoPro (photo: Jun Sato/Getty Images; illustration: The Hustle)

The narrative of striking out on one’s own without any help cuts to the root of the American ethos — and key details in the path to success are often omitted.

Henry David Thoreau — the naturalist famous for his self-reliance — relied on a communal culture to retreat to Walden Pond. His family’s business was a pencil factory — a startup made possible when an uncle fortuitously stumbled upon a load of graphite.

In the glamorous narratives of cowboy settlers heading West, it is seldom mentioned that US government programs like the Homestead Acts gave free land to more than 1.6m people. Throughout the country’s history, not everyone had equal access to such programs.

That led plenty of activists — including Martin Luther King, Jr. — to question the broader narrative of bootstrapping.

“It’s a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself up by his own bootstraps,” King said in a 1967 television interview. “And many Negros by the thousands and millions have been left bootless by all these years of oppression and of a society that deliberately made his color a stigma.”

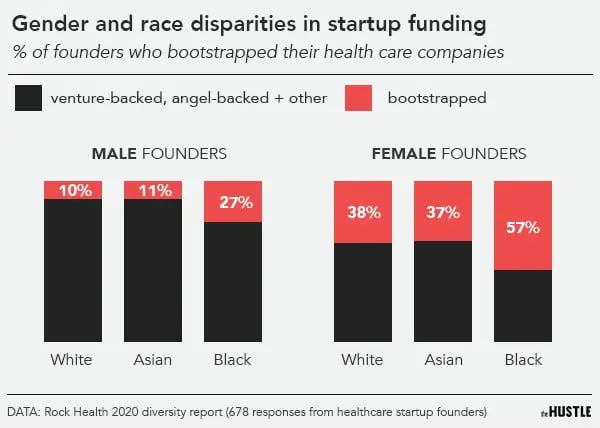

Black and Hispanic founders bootstrap their companies at a higher rate than white or Asian founders — not by choice, but because they often can’t get access to venture funding, at least in the healthcare space.

These disparities are even more pronounced across gender lines.

The Hustle

Even Seth Godin, who wrote the Bible of bootstrapping, admitted in an email interview with The Hustle that only a certain class of people have “the network, the privilege, or the unevenly allocated benefit of the doubt” to use bootstrapping to build a company “that goes public, creates billionaires, and changes the culture.”

In other words, bootstrapping most often isn’t the way to become one of the biggest companies on the planet, despite a few tales of outliers.

Still, Godin defended bootstrapping as a choice most founders should consider to stay focused on the unique product or service they’re hatching.

“It might be a Kickstarter (which is a form of bootstrapper’s leverage that works best if you’ve already earned trust and fans) or it might be a maid service,” he says.

“It could be someone who finds 10 providers in the wedding industry and weaves together a directory or a small digital trade show. It could be a nightclub promoter. It could be a prop specialist in Hollywood who turns her network into a company that produces impossible-to-find items.”

His message boils down to a focus on connecting with customers rather than pitching bankers.

“We need to spend a lot of cycles to fix injustice and inequity and access to opportunity. And we need to do it with urgency,” he concludes. “But I’ve seen so many people who were born on the 95-yard line blink when faced with the chance to bootstrap — it’s mostly a cultural/indoctrination/fear thing.”

The Hustle

But there’s another reason to be wary of the bootstrapping myth, says Rutherford, the business professor.

In his view, new founders can be too suspicious of the help and advice seasoned investors can bring to the table. “Maybe you should adjust or pivot,” he said of some early stages of a company. “And maybe you don’t want to hear that. But you should want to hear all these things before you get going.”

And having enough resources to scale can also mean the difference between success and failure, in an environment where 90% of new ventures fail.

“I get concerned when my students actually think that it’s better to start with less than more,” he said. “It’s a decision that you need to think through very carefully.”