Buckled into a leather chair on his chartered plane, Charles Cohen broke into a cold sweat.

None of Cohen’s 265 employees knew it, but his company, Beenz — then the world’s largest digital currency — stood on the brink of collapse. Now, Cohen was flying to the company’s 15 global offices (most of which he’d never even set foot in, the business had boomed so fast) to assess the damage.

After raising millions in venture capital, battling rivals with mega-celebrity sponsors, and dodging Russian hackers, Beenz would be bankrupt by the end of that year.

Beenz bit the dust 17 years ago, but their story is a textbook example of the danger of investing in a powerful technology before that technology is fully understood.

Welcome to the Beenz Clubhouse

Just 6 months before his airborne farewell tour, a cocky Charles Cohen strode into Beenz’s London office.

Crowded with the swinging legs of an Elvis clock, the half-deflated limbs of a pink party doll, and a Yoda statue belching garbled Star Wars phrases, the office resembled a flophouse for gamers who’d just left their moms’ basements and bought whatever the f*ck they wanted.

But somehow, Cohen and his team had raised $86m from Softbank, Apax Partners, Vivendi, Oracle and other big VC firms. That August, while his buddies cheered for Gladiator, the summer’s blockbuster, Cohen opened his 13th office and pumped his billionth Beenz into circulation.

The 29-year old had turned his crazy idea for a digital currency into a rocket ship — and, fueled by optimistic investors, he was headed for the sun.

The brains behind the Beenz

“I hit on this idea of paying people for their attention and using micro-currency to reward people for doing things which were valuable on the internet,” Cohen told us.

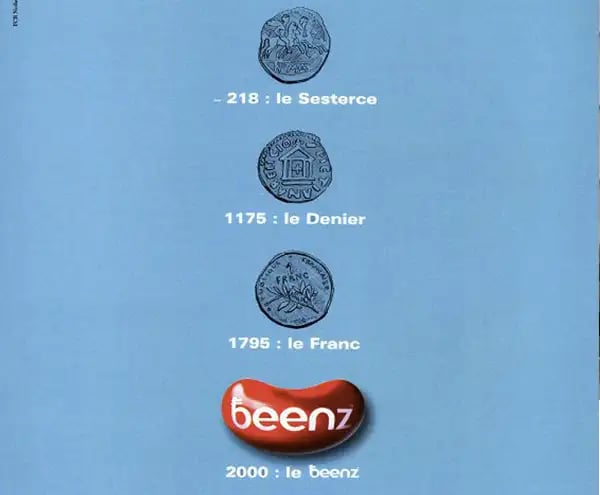

Customers ‘earned’ Beenz by spending money (or time) on a website. Once Beenz accumulated, they became currency, free to be bought, sold or traded like any other coin.

Beenz partners (mostly e-commerce websites) paid $0.01 to issue Beenz, and then earned $0.005 back.

At the time, online payment wasn’t mainstream, but everyone and their mother was excited to see it get there — and Beenz seemed like the company to do it. Larry Ellison, CEO of Oracle, agreed: “Beenz.com is clearly an innovator by developing a true global Internet currency,” he told The Register in March of 1999.

Endorsements like Ellison’s encouraged 150 e-commerce partners to sign with Beenz in its first 5 months (a bookseller named Bezos was among the few partners who turned Beenz down, claiming to have his own online payment solution).

“It’s difficult to predict today just what the pitfalls could be for a scheme that seems to have winners on all sides,” The Independent reported of Beenz at the time. “But Cohen said the company is prepared for the unknown.”

They had just one problem: Whoopi Goldberg

Like any juicy, partially-understood technology, the first wave of digital currency attracted plenty of salesmen eager to sell a new dream.

Beenz’s biggest competitor happened to be Whoopi Goldberg — or, rather, the rival currency, Flooz, that recruited her as its spokeswoman.

Flooz launched nearly a year before Beenz. An ad campaign featuring Goldberg (who was paid in a mixture of Flooz currency and Flooz stock) boosted sales from $3m to $25m between 1999 and 2000 — enough to challenge Beenz for digital currency’s heavyweight title.

So, Beenz did what any well-funded currency company would do: it invested heavily in growth, pouring venture capital into everything from new markets to moonshot partnerships.

Drinking the currency Kool-Aid

Neil Forrester, Cohen’s co-founder and friend from Oxford, had come all the way from a starring role in MTV’s The Real World: London to pursue the Beenz dream. Forrester was tasked with bringing Beenz to new markets, directing a small army that translated the platform into 15 languages.

Beenz paid up-and-coming tech companies to design products for the burgeoning business, claiming Beenz would trade on cell-phones, game consoles, interactive televisions (grandaddies of smart TVs), and Mondex smartcards (early digital wallets).

The company and its investors radiated boundless optimism. In 2000, Cohen told Time that he expected to see Beenz listed against major currencies within 5 years. After all, the whole world seemed to be betting on them.

At one point, the UK’s Financial Services Authority searched the Beenz office to investigate the unlicensed ‘Bank of Beenz.’ The team merely laughed.“Beenz,” they explained, “[were] a radical alternative to money” that would “create a new generation of e-millionaires.”

Just 4 months later, the trouble began…

“We decided we needed to be very careful where we spent our money,” Cohen explained to The Register after firing 25 employees in December of 2000. He told reporters the company had plenty of cash left — but things at Beenz were bleaker than Cohen admitted to the press.

While Beenz had developed a ‘radical alternative to money,’ companies like Amazon and Visa built simple online payment options using credit cards — and when Beenz’s partners discovered them, they up and left.

“Talk about the air going out of the balloon,” Cohen told us. “Quite literally, our customers disappeared. It wasn’t that they started buying less; they just disappeared.”

Meanwhile, at Flooz, the sh*t really hit the fan: The company unknowingly sold $300k in currency to members of an organized crime syndicate in Russia and the Philippines, forcing a liquidity crunch that left Flooz with the most creditors (325k) in bankruptcy history.

By April, the Beenz staff shrank from 265 to just 30, and 13 of the company’s 15 offices shuttered and in May, the company announced plans to find a buyer.

Then, on August 16th, Beenz users received this message:

“The operation of the Beenz economy will be terminated at 12.01am Eastern Standard Time on August 26 2001. No Beenz earning or spending transaction will be honoured after that date […] Thank you for participating in the Beenz economy.”

The very same day, Flooz announced its bankruptcy.

The crypto craze looks awfully familiar

When entrepreneurs race to create products from cutting-edge tech, some have value — but many don’t.

And, like the Beenz bubble born out of online payments, today’s crypto craze is a response to a powerful new technology: Blockchain.

Blockchain is poised to revolutionize industries, but, it’s also unleashed a speculative tornado of titanic proportions. In fact, cryptocurrency is even more overinvested than digital currency in Cohen’s day (Block.one raised $4B in an ICO without telling its investors what it’s product is).

“Cryptocurrency is like a gold rush in the sense that there’s a massive area of land that’s just opened up, but nobody really knows where the gold is,” Cohen says. “Everybody just takes a patch and digs — but it’s gonna be some time before you see the winners and losers.”

Finding the diamond in the Beenz

To identify which emerging tech companies will go the distance, you first need to distinguish novelty from innovation.

Novelty, according to Cohen, is when you “make something just because some idiot’s gonna buy it off you. Innovation is an application of technology that has some value to people.”

And, more often than not, simple solutions outlast fancy fixes.

Amazon and Visa beat Beenz by using new technology to fix an antiquated system, not by inventing an entirely new one. This time around, Cohen expects the same process to unfold — resulting in a few regulated exchanges and companies built around practical solutions.

Already, Coinbase and Circle, two large digital currency platforms, are racing towards regulation to capture bigger revenue. Telegram, the 2nd highest-funded ICO after Block.one, is using channeling its $1.7B into improving its secure messaging app.

But, when we asked Cohen which cryptocurrencies he had invested in, he chuckled like an uncle who’s seen it all before…

“I absolutely do not have any money in cryptocurrency,” he said. “Funny enough, I now work in the gambling industry. But I don’t gamble with my own money.”

There will be winners and losers in the crypto gold rush. But this time, Cohen won’t be the one picking them.